Gravity

[2] However, gravity is the most significant interaction between objects at the macroscopic scale, and it determines the motion of planets, stars, galaxies, and even light.

Gravity also has many important biological functions, helping to guide the growth of plants through the process of gravitropism and influencing the circulation of fluids in multicellular organisms.

Current models of particle physics imply that the earliest instance of gravity in the universe, possibly in the form of quantum gravity, supergravity, or a gravitational singularity, along with ordinary space and time, developed during the Planck epoch (up to 10−43 seconds after the birth of the universe), possibly from a primeval state, such as a false vacuum, quantum vacuum or virtual particle, in a currently unknown manner.

[8] While Aristotle's view was widely accepted throughout Ancient Greece, there were other thinkers such as Plutarch who correctly predicted that the attraction of gravity was not unique to the Earth.

[11] Two centuries later, the Roman engineer and architect Vitruvius contended in his De architectura that gravity is not dependent on a substance's weight but rather on its "nature".

[13] In 628 CE, the Indian mathematician and astronomer Brahmagupta proposed the idea that gravity is an attractive force that draws objects to the Earth and used the term gurutvākarṣaṇ to describe it.

The Persian intellectual Al-Biruni believed that the force of gravity was not unique to the Earth, and he correctly assumed that other heavenly bodies should exert a gravitational attraction as well.

[19] De Soto may have been influenced by earlier experiments conducted by other Dominican priests in Italy, including those by Benedetto Varchi, Francesco Beato, Luca Ghini, and Giovan Bellaso which contradicted Aristotle's teachings on the fall of bodies.

[19] The mid-16th century Italian physicist Giambattista Benedetti published papers claiming that, due to specific gravity, objects made of the same material but with different masses would fall at the same speed.

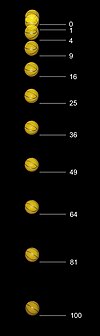

[21] In the late 16th century, Galileo Galilei's careful measurements of balls rolling down inclines allowed him to firmly establish that gravitational acceleration is the same for all objects.

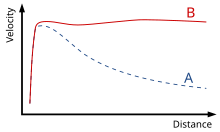

[22] Galileo postulated that air resistance is the reason that objects with a low density and high surface area fall more slowly in an atmosphere.

In that year, the French astronomer Alexis Bouvard used this theory to create a table modeling the orbit of Uranus, which was shown to differ significantly from the planet's actual trajectory.

In 1846, the astronomers John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier independently used Newton's law to predict Neptune's location in the night sky, and the planet was discovered there within a day.

Einstein's description of gravity was quickly accepted by the majority of physicists, as it was able to explain a wide variety of previously baffling experimental results.

Solving these equations amounts to calculating a precise value for the metric tensor (which defines the curvature and geometry of spacetime) under certain physical conditions.

The situation gets even more complicated when considering the interactions of three or more massive bodies (the "n-body problem"), and some scientists suspect that the Einstein field equations will never be solved in this context.

[59] Despite its success in predicting the effects of gravity at large scales, general relativity is ultimately incompatible with quantum mechanics.

This is because general relativity describes gravity as a smooth, continuous distortion of spacetime, while quantum mechanics holds that all forces arise from the exchange of discrete particles known as quanta.

[60] As a result, modern researchers have begun to search for a theory that could unite both gravity and quantum mechanics under a more general framework.

[65] Still, since its development, an ongoing series of experimental results have provided support for the theory:[65] In 1919, the British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington was able to confirm the predicted gravitational lensing of light during that year's solar eclipse.

Although Eddington's analysis was later disputed, this experiment made Einstein famous almost overnight and caused general relativity to become widely accepted in the scientific community.

[68] In 1959, American physicists Robert Pound and Glen Rebka performed an experiment in which they used gamma rays to confirm the prediction of gravitational time dilation.

By sending the rays down a 74-foot tower and measuring their frequency at the bottom, the scientists confirmed that light is Doppler shifted as it moves towards a source of gravity.

The observed shift also supports the idea that time runs more slowly in the presence of a gravitational field (many more wave crests pass in a given interval).

[69] The time delay of light passing close to a massive object was first identified by Irwin I. Shapiro in 1964 in interplanetary spacecraft signals.

[71] This discovery confirmed yet another prediction of general relativity, because Einstein's equations implied that light could not escape from a sufficiently large and compact object.

This phenomenon was first confirmed by observation in 1979 using the 2.1 meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, which saw two mirror images of the same quasar whose light had been bent around the galaxy YGKOW G1.

[77] Every planetary body (including the Earth) is surrounded by its own gravitational field, which can be conceptualized with Newtonian physics as exerting an attractive force on all objects.

It also opens the way for practical observation and understanding of the nature of gravity and events in the Universe including the Big Bang.

[88] This means that if the Sun suddenly disappeared, the Earth would keep orbiting the vacant point normally for 8 minutes, which is the time light takes to travel that distance.