Great Chinese Famine

[1] The major contributing factors in the famine were the policies of the Great Leap Forward (1958 to 1962) and people's communes, launched by Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party Mao Zedong, such as inefficient distribution of food within the nation's planned economy; requiring the use of poor agricultural techniques; the Four Pests campaign that reduced sparrow populations (which disrupted the ecosystem); over-reporting of grain production; and ordering millions of farmers to switch to iron and steel production.

[4][6][8][15][17][18] During the Seven Thousand Cadres Conference in early 1962, Liu Shaoqi, then President of China, formally attributed 30% of the famine to natural disasters and 70% to man-made errors ("三分天灾, 七分人祸").

[8][19][20] After the launch of Reforms and Opening Up, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officially stated in June 1981 that the famine was mainly due to the mistakes of the Great Leap Forward as well as the Anti-Right Deviation Struggle, in addition to some natural disasters and the Sino-Soviet split.

[26] Mao Zedong himself suggested, in a discussion with Field Marshal Montgomery in Autumn 1961, that "unnatural deaths" exceeded 5 million in 1960–1961, according to a declassified CIA report.

[65] The mortality in the birth and death rates both peaked in 1961 and began recovering rapidly after that, as shown on the chart of census data displayed here.

[69][75] The Great Chinese Famine was caused by a combination of radical agricultural policies, social pressure, economic mismanagement, and natural disasters such as droughts and floods in farming regions.

In 2008, former deputy editor of Yanhuang Chunqiu and author Yang Jisheng would summarize his perspective of the effect of the production targets as an inability for supply to be redirected to where it was most demanded: In Xinyang, people starved at the doors of the grain warehouses.

[78] However, dire hunger did not set in to places like Da Fo village until 1960,[79] and the public dining hall participation rate was found not to be a meaningful cause of famine in Anhui and Jiangxi.

[81] Along with collectivization, the central government decreed several changes in agricultural techniques that would be based on the ideas of later-discredited Soviet agronomist Trofim Lysenko.

Second, it prompted the Chinese leadership, especially Zhou Enlai, to speed up grain exports to secure more foreign currency to purchase capital goods needed for industrialization.

[87] In addition, policies from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the central government, particularly the Three Red Banners and the Socialist Education Movement (SEM), proved to be ideologically detrimental to the worsening famine.

The implementation of the Mass line, one of the three banners which told people to "go all out, aim high, and build socialism with greater, better, and more economical results", is cited in connection to the pressures officials felt to report a superabundance of grain.

[89] The SEM also led to the establishment of conspiracy theories in which the peasants were believed to be pretending to be hungry in order to sabotage the state grain purchase.

[92] In an environment of conspiracy theories directed against peasants, saving extra grain for a family to eat, espousing the belief that the Great Leap Forward should not be implemented, or merely not working hard enough were all seen as forms of "conservative rightism".

Zhang Kaifan, a party secretary and deputy-governor of the province, heard rumours of a famine breaking out in Anhui and disagreed with many of Zeng's policies.

The leaders of Jiangxi publicly opposed some of the Great Leap programs, quietly made themselves unavailable, and even appeared to take a passive attitude towards the Maoist economy.

[4][14][15][112] According to published data from Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences (中国气象科学研究院), the drought in 1960 was not uncommon and its severity was only considered "mild" compared to that in other years—it was less serious than those in 1955, 1963, 1965–1967, and so on.

[113] Moreover, Yang Jisheng, a senior journalist from Xinhua News Agency, reports that Xue Muqiao, then head of the National Statistics Bureau of China, said in 1958, "We give whatever figures the upper-level wants" to overstate natural disasters and relieve official responsibility for deaths due to starvation.

[16] According to Basil Ashton: Many foreign observers felt that these reports of weather-related crop failures were designed to cover up political factors that had led to poor agricultural performance.

[8]Despite these claims, other scholars have provided provincial-level demographic panel data which quantitatively proved that weather was also an important factor, particularly in those provinces which experienced excessively wet conditions.

[117] The local officials became trapped by these sham demonstrations to Mao, and exhorted the peasants to reach unattainable goals, by "deep ploughing and close planting", among other techniques.

[74] Yang Jisheng, a retired Chinese reporter, said: When the Guangshan County post office discovered an anonymous letter to Beijing disclosing starvation deaths, the public security bureau began hunting down the writer.

It was subsequently determined that the writer worked in Zhengzhou and had written the letter upon returning to her home village and seeing people starving to death.

[118][page needed][119] This kind of deception was far from uncommon; a famous propaganda picture from the famine shows Chinese children from Shandong province ostensibly standing atop a field of wheat, so densely grown that it could apparently support their weight.

[77] In response to the famine, the Nationalist government in Taipei delivered food, along with propaganda leaflets of Chiang Kai-shek, to the mainland via parachute drops conducted by the ROC air force.

[120][121] In April and May 1961, Liu Shaoqi, then President of the People's Republic of China, concluded after 44 days of field research in villages of Hunan that the causes of the famine were 30% natural disaster and 70% human error (三分天灾, 七分人祸).

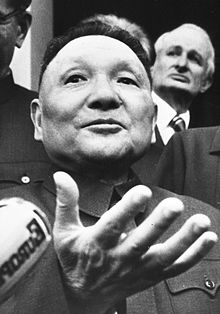

[123][124] The failure of the Great Leap Forward as well as the famine forced Mao Zedong to withdraw from active decision-making within the CCP and the central government, and turn various future responsibilities over to Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping.

[125] A series of economic reforms were carried out by Liu and Deng and others, including policies such as sanzi yibao (三自一包) which allowed free market and household responsibility for agricultural production.

During the "Boluan Fanzheng" period in June 1981, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officially changed the name to "Three Years of Difficulty", and stated that the famine was mainly due to the mistakes of the Great Leap Forward as well as the Anti-Right Deviation Struggle, in addition to some natural disasters and the Sino-Soviet split.

[2][3] Academic studies on the Great Chinese Famine also became more active in mainland China after 1980, when the government started to release some demographic data to the public.