Great Northern Expedition

The Great Northern Expedition (Russian: Великая Северная экспедиция) or Second Kamchatka Expedition (Russian: Вторая Камчатская экспедиция) was one of the largest exploration enterprises in history, mapping most of the Arctic coast of Siberia and some parts of the North American coastline, greatly reducing "white areas" on maps.

It definitively refuted the legend of a land mass in the north Pacific, and did ethnographic, historic, and scientific research into Siberia and Kamchatka.

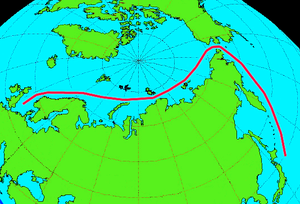

When the expedition failed to round the north-east tip of Asia, the dream of an economically viable Northeast passage, sought since the 16th century, was at an end.

At their final meeting at Bad Pyrmont in 1716, Leibniz spoke of a possible land bridge between northeastern Asia and the North America, a point of great relevance in contemporary discussion about the origins of humanity, among other matters.

To resolve the question of a land bridge, Peter the Great sent in 1719 the geodesists Iwan Jewreinow (1694–1724) and Fjodor Luschin (died 1727) to the easternmost reaches of his empire.

Despite the new knowledge about the northeast coast of Siberia, Bering's report led to divisive debate, because the question of a connection with North America remained unanswered.

[5] The central goals in Bering's vision for the new expedition was the survey of the northern coast of the Russian Empire; the expansion of the port of Okhotsk as the gateway to the Pacific Ocean; the search for a sea route to North America and Japan; the opening of access to Siberian natural resources; and finally, the securing of Russian sovereignty in the eastern parts of Asia.

The completion of this mission set the foundations for determining the status of the north east passage as a possible connection between Europe and the Pacific Ocean.

The second Pacific division was under the command of the Danish-born Russian captain Martin Spanberg (d. 1761), who had accompanied Bering on the First Kamchatka Expedition, and had been charged with exploring the sea route from Okhotsk to Japan and China.

Johann Georg Gmelin (1709–1755) was responsible for research into the plant and animal world as well as the mineral characteristics of the regions to be explored.

Gmelin was a natural philosopher and botanist from Württemberg, who had studied in Tübingen and had researched the chemical composition of curative waters.

Among other things, Duvernoi wanted to find out whether the peoples of Siberia could move their ears, whether their uvulas were simple, or split into two or three parts, whether Siberian males had milk in their breasts, etc.

[9] The physicist Daniel Bernoulli (1700–1782) authored instructions intended for Croyère and Gmelin about the carrying out of series of physical observations.

His chief goals consisted of researching the history of all the cities the expedition would visit and collecting information about the languages of the groups they would meet along the way.

The two Pacific divisions of the expedition, led by Martin Spanberg and Vitus Bering, left St. Petersburg in February and April 1733, while the academic group departed on August 8, 1733.

In addition to the academy members Gmelin, Müller and Croyère, the group also included the Russian students Stepan Krasheninnikov, Alexei Grolanov, Luka Ivanov, Wassili Tretjakov and Fyodor Popov, the translator (also a student) Ilya Jaontov, the geodesists Andrei Krassilnikov, Moisei Uschakov, Nikifor Tschekin and Alexandr Ivanov, the instrument maker Stepan Ovsjanikov, and the painters Johann Christian Berckhan and Johann Wilhelm Lürsenius.

In May, Gmelin and Müller separated from the rest of the group, who were put under Croyères' leadership, and travelled until December 1734 to the Irtysh River, and then onwards to Semipalatinsk, Kusnezk near Tomsk, and then onto Yeniseysk.

In the meantime, Müller located and investigated area archives and made copies and transcriptions, while Gmelin studied plants he had collected over the course of the summer.

Almost all the members of the two Pacific divisions of the expedition had gathered there in the meantime, and as a result, Gmelin and Müller experienced difficulties in locating accommodation.

Though aboard the St. Paul with Vitus Bering, Georg Wilhelm Steller was a naturalist by trade and contributed a considerable amount to the scientific observation and recording on the expedition.

[11][12] He sent a group of men ashore in a long boat, making them the first Europeans to land on the northwestern coast of North America.

On roughly July 16, 1741, Bering and the crew of St. Peter sighted a towering peak on the Alaska mainland, Mount Saint Elias.

On the return journey, with only 12 members of the crew able to move and the rigging rapidly failing, the expedition was shipwrecked on what later became known as Bering Island.

[17] The sea otter pelts they brought, soon judged to be the finest fur in the world, would spark Russian settlement in Alaska.