Great Observatories program

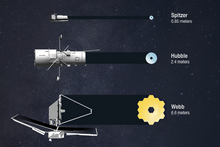

NASA's series of Great Observatories satellites are four large, powerful space-based astronomical telescopes launched between 1990 and 2003.

It was launched in 1990 aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery during STS-31, but its main mirror had been ground incorrectly, resulting in spherical aberration that compromised the telescope's capabilities.

It was launched in 1999 aboard Columbia during STS-93 into an elliptical high-Earth orbit, and was initially named the Advanced X-ray Astronomical Facility (AXAF).

The concept of a Great Observatory program was first proposed in the 1979 NRC report "A Strategy for Space Astronomy and Astrophysics for the 1980s".

[1] This report laid the essential groundwork for the Great Observatories and was chaired by Peter Meyer (through June 1977) and then by Harlan J. Smith (through publication).

NASA's "Great Observatories" program used four separate satellites, each designed to cover a different part of the spectrum in ways which terrestrial systems could not.

This perspective enabled the proposed X-ray and InfraRed observatories to be appropriately seen as a continuation of the astronomical program begun with Hubble and CGRO rather than competitors or replacements.

[7] Congress eventually approved funding of US$36 million for 1978, and the design of the LST began in earnest, aiming for a launch date of 1983.

In 1976 the Chandra X-ray Observatory (called AXAF at the time) was proposed to NASA by Riccardo Giacconi and Harvey Tananbaum.

Preliminary work began the following year at Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO).

This eliminated the possibility of improvement or repair by the Space Shuttle but put the observatory above the Earth's radiation belts for most of its orbit.

This approach was developed in an era when the Shuttle program was presumed to be capable of supporting weekly flights of up to 30 days duration.

The 1985 Spacelab-2 flight aboard STS-51-F confirmed the Shuttle environment was not well suited to an onboard infrared telescope, and a free-flying design was better.

It was originally intended to be so launched, but after the Challenger disaster, the Centaur LH2/LOX upper stage that would have been required to push it into a heliocentric orbit was banned from Shuttle use.

Since the Earth's atmosphere prevents X-rays, gamma-rays[14] and far-infrared radiation from reaching the ground, space missions were essential for the Compton, Chandra and Spitzer observatories.

It followed the three NASA HEAO Program satellites, notably the highly successful Einstein Observatory, which was the first to demonstrate the power of grazing-incidence, focusing X-ray optics, giving spatial resolution an order of magnitude better than collimated instruments (comparable to optical telescopes), with an enormous improvement in sensitivity.

Chandra's large size, high orbit, and sensitive CCDs allowed observations of very faint X-ray sources.

Spitzer's instruments took advantage of the rapid advances in infrared detector technology since IRAS, combined with its large aperture, favorable fields of view, and long life.

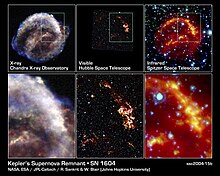

Studying X-ray and gamma-ray objects with Hubble, as well as Chandra and Compton, gives accurate size and positional data.

Worthwhile targets are often found with ground telescopes, which are cheaper, or with smaller space observatories, which are sometimes expressly designed to cover large areas of the sky.

Further spectroscopy by Spitzer can determine the chemical composition of the object's surface, which limits its possible albedos, and therefore sharpens the low size estimate.

At the opposite end of the cosmic distance ladder, observations made with Hubble, Spitzer and Chandra have been combined in the Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey to yield a multi-wavelength picture of galaxy formation and evolution in the early Universe.

In 2019, the four teams will turn their final reports over to the National Academy of Sciences, whose independent Decadal Survey committee advises NASA on which mission should take top priority.