Great Renunciation

To prevent his son from turning to religious life, Prince Siddhārtha's father and rāja of the Śākya clan Śuddhodana did not allow him to see death or suffering, and distracted him with luxury.

But he continued to ponder about religious questions, and when he was 29 years old, he saw for the first time in his life what became known in Buddhism as the four sights: an old man, a sick person and a corpse, as well as an ascetic that inspired him.

The story of Prince Siddhārtha's renunciation illustrates the conflict between lay duties and religious life, and shows how even the most pleasurable lives are still filled with suffering.

The historical basis of Siddhārtha Gautama's life has been affected by his association with the ideal king (cakravartin), inspired by the growth of the Maurya empire a century after he lived.

The literal interpretation of the confrontation with the four sights—seeing old age, sickness and death for the first time in his life—is generally not accepted by historians, but seen as symbolical for a growing and shocking existential realization, which may have started in Gautama's early childhood.

[10][note 1] Sinhalese commentators have composed the Pāli language Jātakanidāna, a commentary to the Jātaka from the 2nd – 3rd century CE, which relates the Buddha's life up until the donation of the Jetavana Monastery.

[25] In some later texts, this is extensively described, explaining how the young prince looked at the animals on the courtyard eating each other, and him realizing the suffering (Sanskrit: duḥkha, Pali: dukkha) inherent in all existence.

[41][note 5] The Pāli account claims that when he received the news of his son's birth he replied "rāhulajāto bandhanaṃ jātaṃ", meaning 'A rāhu is born, a fetter has arisen',[44][45] that is, an impediment to the search for enlightenment.

[59][58] Indologist Bhikkhu Telwatte Rahula notes that there is an irony here, in that the women originally sent by the rāja Śuddhodana to entice and distract the prince from thinking to renounce the worldly life, eventually accomplish just the opposite.

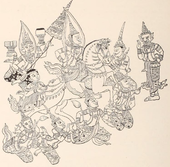

The texts continue by relating that Prince Siddhārtha was confronted by Mara, the personification of evil in Buddhism, who attempted to tempt him to change his mind and become a cakravartin instead, but to no avail.

[80] Scholar of iconography Anna Filigenzi argues that this exchange indicates Gautama's choice to engage in a more "primitive" kind of society, removed from urban life.

[88][89] Buddhist studies scholar John S. Strong notes that these alternative accounts draw a parallel between the quest for enlightenment and Yaśodharā's path to being a mother, and eventually, they both are accomplished at the same time.

[92] Archaeologist Alfred Foucher pointed out that the Great Departure marks a point in the biographies of the Buddha from which he was no longer a prince, and no longer asked the deities for assistance: "And as such he found himself in an indifferent world, without guidance or support, confronted with both the noble task of seeking mankind's salvation and the lowly but pressing one of securing his daily bread ..."[59][93] The sacrifice meant that he discarded his royal and caste obligations to affirm the value of spiritual enlightenment.

[97] The Buddha's motivation is described as a form of strong religious agitation (Sanskrit and Pali: saṃvega), a sense of fear and disgust that arises when confronted with the transient nature of the world.

[99] The early Buddhist texts state that Prince Siddhārtha's motivation in renouncing the palace life was his existential self-examination, being aware that he would grow old, become sick and die.

[118] Buddhologist André Bareau (1921–1993) argued that the association that is made between the life of the Buddha and that of the cakravartin may have been inspired by the rapid growth of the Maurya Empire in 4th-century BCE India, though it could also be a pre-Buddhist tradition.

[130] In the words of Buddhist studies scholar Peter Harvey: In this way, the texts portray an example of the human confrontation with frailty and mortality; for while these facts are 'known' to us all, a clear realization and acceptance of them often does come as a novel and disturbing insight.

[131] Drawing from a theory by philologist Friedrich Weller [de], Buddhist studies scholar Bhikkhu Anālayo argues, on the other hand, that the four sights might originate in pictorial depictions used in early Buddhism for didactic purposes.

[99][132] With regard to the restrictions enforced by Śuddhodana, Schumann said it is probable that the rāja tried to prevent his son from meeting with free-thinking samaṇa and paribbājaka wandering mendicants assembling in nearby parks.

[141] Buddhist studies scholar John S. Strong hypothesizes that the Mūlasarvāstivāda and Mahāvastu version of the story of the prince conceiving a child on the eve of his departure was developed to prove that the Buddha was not physically disabled in some way.

[142] The motif of the sleeping harem preceding the renunciation is widely considered by scholars to be modeled on the story of Yasa, a guild-master and disciple of the Buddha, who is depicted having a similar experience.

Orientalist Edward Johnston did not want to make any statements about this, however, preferring to wait for more evidence, though he did acknowledge that Aśvaghoṣa "took pleasure" in comparing the Buddha's renunciation with Rāma's leaving for the forest.

[145] In his analysis of Indian literature, scholar of religion Graeme Macqueen observes a recurring contrast between the figure of the king and that of the ascetic, who represent external and internal mastery, respectively.

[149] On a similar note, Xuan Zang claimed that the pillar of Aśoka which marks Lumbinī was once decorated at the top with a horse figure, which likely was Kaṇṭhaka, symbolizing the Great Departure.

In this story, titled Balawhar wa-Būdāsf, the main character is horrified by his harem attendants and decides to leave his father's palace to seek spiritual fulfillment.

[174] In the 19th century, the Great Renunciation was a major theme in the biographical poem The Light of Asia by the British poet Edwin Arnold (1832–1904), to the extent that it became the subtitle of the work.

[180] The focus on the renunciation in the life of the Buddha contributed to the popularity of the work, as well as the fact that Arnold left out many miraculous details of the traditional accounts to increase its appeal to a post-Darwinian audience.

[181] Moreover, Arnold's depiction of Prince Siddhārtha as an active and compassionate truth-seeker defying his father's will and leaving the palace life went against the stereotype of the weak-willed and fatalistic Oriental, but did conform with the middle-class values of the time.

Arnold also gave a much more prominent role to Yaśodharā than traditional sources, having Prince Siddhārtha explain his departure to his wife extensively, and even respectfully circumambulating her before leaving.

[186] Comparative literature scholar Dominique Jullien concludes that the story of the Great Renunciation, the widespread narrative of the king and the ascetic, is a confrontation between a powerful and powerless figure.