Great Western Railway

It was founded in 1833, received its enabling act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran its first trains in 1838 with the initial route completed between London and Bristol in 1841.

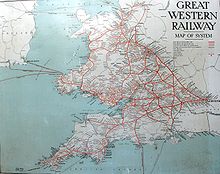

The GWR was called by some "God's Wonderful Railway" and by others the "Great Way Round" but it was famed as the "Holiday Line", taking many people to English and Bristol Channel resorts in the West Country as well as the far southwest of England such as Torquay in Devon, Minehead in Somerset, and Newquay and St Ives in Cornwall.

Firstly, he chose to use a broad gauge of 7 ft (2,134 mm) to allow for the possibility of large wheels outside the bodies of the rolling stock which could give smoother running at high speeds.

[9][10] George Thomas Clark played an important role as an engineer on the project, reputedly taking the management of two divisions of the route including bridges over the River Thames at Lower Basildon and Moulsford and of Paddington Station.

[11] Involvement in major earth-moving works seems to have fed Clark's interest in geology and archaeology and he, anonymously, authored two guidebooks on the railway: one illustrated with lithographs by John Cooke Bourne;[12] the other, a critique of Brunel's methods and the broad gauge.

The cutting was the scene of a railway disaster two years later when a goods train ran into a landslip; ten passengers who were travelling in open trucks were killed.

The section from Wootton Bassett Road to Chippenham was opened on 31 May 1841, as was Swindon Junction station where the Cheltenham and Great Western Union Railway (C&GWUR) to Cirencester connected.

This rival company had continued to push westwards over its Exeter and Crediton line and arrived in Plymouth later in 1876, which spurred the South Devon Railway to also amalgamate with the Great Western.

One final new broad-gauge route was opened on 1 June 1877, the St Ives branch in west Cornwall, although there was also a small extension at Sutton Harbour in Plymouth in 1879.

The principal new lines opened were:[31] The generally conservative GWR made other improvements in the years before World War I such as restaurant cars, better conditions for third class passengers, steam heating of trains, and faster express services.

These were largely at the initiative of T. I. Allen, the Superintendent of the Line and one of a group of talented senior managers who led the railway into the Edwardian era: Viscount Emlyn (Earl Cawdor, Chairman from 1895 to 1905); Sir Joseph Wilkinson (general manager from 1896 to 1903), his successor, the former chief engineer Sir James Inglis; and George Jackson Churchward (the Chief Mechanical Engineer).

[36] GWR designs of locomotives and rolling stock continued to be built for a while and the region maintained its own distinctive character, even painting for a while its stations and express trains in a form of chocolate and cream.

[41] Swindon was also the junction for a line that ran north-westwards to Gloucester then south-westwards on the far side of the River Severn to reach Cardiff, Swansea and west Wales.

[49] Brunel envisaged the GWR continuing across the Atlantic Ocean and built the SS Great Western to carry the railway's passengers from Bristol to New York.

[50] Most traffic for North America soon switched to the larger port of Liverpool (in other railways' territories) but some transatlantic passengers were landed at Plymouth and conveyed to London by special train.

[3] The principal express services were often given nicknames by railwaymen but these names later appeared officially in timetables, on headboards carried on the locomotive, and on roofboards above the windows of the carriages.

For instance, the late-morning Flying Dutchman express between London and Exeter was named after the winning horse of the Derby and St Leger races in 1849.

From the following year a number of small locomotives were fitted so that they could work with these trailers, the combined sets becoming known as "autotrains" and eventually replacing the steam rail motors.

The wagons provided for both these traffic flows (both those owned by the GWR and the mining companies) were fitted with end doors that allowed their loads to be tipped straight into the ships' holds using wagon-tipping equipment on the dockside.

This was followed by other services to create a network of fast trains between the major centres of production and population that were scheduled to run at speeds averaging 35 mph (56 km/h).

[85] Joseph Armstrong's early death in 1877 meant that the next phase of motive power design was the responsibility of William Dean who developed express 4-4-0 types rather than the single-driver 2-2-2s and 4-2-2s that had hauled fast trains up to that time.

From the time of Armstrong's arrival all new locomotives – both broad and standard – were given numbers, including broad-gauge ones that had previously carried names when they were acquired from other railways.

[108] Later, GWR road motors operated tours to popular destinations not served directly by train, and its ships offered cruises from places such as Plymouth.

[109] Redundant carriages were converted to camp coaches and placed at country or seaside stations such as Blue Anchor and Marazion and hired to holidaymakers who arrived by train.

These included Holiday Haunts, describing the attraction of the different parts of the GWR system,[111] and regional titles such as S. P. B. Mais's Cornish Riviera and A. M. Bradley's South Wales: The Country of Castles.

[112] The Great Western Railway effectively created the modern day tourist spots of the West Country and the southwest part of Wales that had previously been very difficult to reach.

Illustrated with photographs on almost every opening, it recounts the history of the GWR as a locomotive-using and building company, the construction and development of Swindon Works, and the training of those employed there.

Preserved GWR lines include those from Totnes to Buckfastleigh, Paignton to Kingswear, Bishops Lydeard to Minehead, Kidderminster to Bridgnorth and Cheltenham to Broadway.

This is seen not only at the large stations such as Paddington (built 1851,[126] extended 1915)[127] and Temple Meads (1840,[128] 1875[129] & 1935)[130] but other places such as Bath Spa (1840),[131] Torquay (1878),[132] Penzance (1879),[133] Truro (1897),[134] and Newton Abbot (1927).

[135] Many small stations are little changed from when they were opened, as there has been no need to rebuild them to cope with heavier traffic; good examples can be found at Yatton (1841), Frome (1850, Network Rail's last surviving Brunel-style train shed),[131] Bradford-on-Avon (1857), and St Germans (1859).

• Broad gauge – blue (top)

• Mixed gauge – green (middle)

• Standard gauge – orange (bottom)

| Values to chart | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 31 December | Broad | Mixed | Standard |

| 1851 | 269 miles (433 km) | 3 miles (5 km) | 0 miles (0 km) |

| 1856 | 298 miles (480 km) | 124 miles (200 km) | 75 miles (121 km) |

| 1861 | 327 miles (526 km) | 182 miles (293 km) | 81 miles (130 km) |

| 1866 | 596 miles (959 km) | 237 miles (381 km) | 428 miles (689 km) |

| 1871 | 524 miles (843 km) | 141 miles (227 km) | 655 miles (1,054 km) |

| 1876 | 268 miles (431 km) | 274 miles (441 km) | 1,481 miles (2,383 km) |

| 1881 | 210 miles (340 km) | 254 miles (409 km) | 1,674 miles (2,694 km) |

| 1886 | 187 miles (301 km) | 251 miles (404 km) | 1,918 miles (3,087 km) |

| 1891 | 171 miles (275 km) | 252 miles (406 km) | 1,982 miles (3,190 km) |