Ancient Greek architecture

This is particularly so in the case of temples where each building appears to have been conceived as a sculptural entity within the landscape, most often raised on high ground so that the elegance of its proportions and the effects of light on its surfaces might be viewed from all angles.

Hence temples were placed on hilltops, their exteriors designed as a visual focus of gatherings and processions, while theatres were often an enhancement of a naturally occurring sloping site where people could sit, rather than a containing structure.

[6] The gleaming marble surfaces were smooth, curved, fluted, or ornately sculpted to reflect the sun, cast graded shadows and change in colour with the ever-changing light of day.

Both these civilizations came to an end around 1100 BC, that of Crete possibly because of volcanic devastation, and that of Mycenae because of an invasion by the Dorian people who lived on the Greek mainland.

There is a clear division between the architecture of the preceding Mycenaean and Minoan cultures and that of the ancient Greeks, with much of the techniques and an understanding of their style being lost when these civilisations fell.

It is probable that many of the earliest houses were simple structures of two rooms, with an open porch or pronaos, above which rose a low pitched gable or pediment.

[22] Greek towns of substantial size also had a palaestra or a gymnasium, the social centre for male citizens which included spectator areas, baths, toilets and club rooms.

Although the existent buildings of the era are constructed in stone, it is clear that the origin of the style lies in simple wooden structures, with vertical posts supporting beams which carried a ridged roof.

The posts and beams divided the walls into regular compartments which could be left as openings, or filled with sun dried bricks, lathes or straw and covered with clay daub or plaster.

The indication is that initially all the rafters were supported directly by the entablature, walls and hypostyle, rather than on a trussed wooden frame, which came into use in Greek architecture only in the 3rd century BC.

[34] Spreading rapidly, roof tiles were within fifty years in evidence for a large number of sites around the Eastern Mediterranean, including Mainland Greece, Western Asia Minor, Southern and Central Italy.

[34] As a side-effect, it has been assumed that the new stone and tile construction also ushered in the end of overhanging eaves in Greek architecture, as they made the need for an extended roof as rain protection for the mudbrick walls obsolete.

[33] Vaults and arches were not generally used, but begin to appear in tombs (in a "beehive" or cantilevered form such as used in Mycenaea) and occasionally, as an external feature, exedrae of voussoired construction from the 5th century BC.

The ratio is similar to that of the growth patterns of many spiral forms that occur in nature such as rams' horns, nautilus shells, fern fronds, and vine tendrils and which were a source of decorative motifs employed by ancient Greek architects as particularly in evidence in the volutes of capitals of the Ionic and Corinthian Orders.

[38] Banister Fletcher calculated that the stylobate curves upward so that its centres at either end rise about 65 millimetres (2.6 inches) above the outer corners, and 110 mm (4.3 in) on the longer sides.

While the three orders are most easily recognizable by their capitals, they also governed the form, proportions, details and relationships of the columns, entablature, pediment, and the stylobate.

[41] By the Early Classical period, with the decoration of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (486–460 BC), the sculptors had solved the problem by having a standing central figure framed by rearing centaurs and fighting men who are falling, kneeling and lying in attitudes that fit the size and angle of each part of the space.

[38] The famous sculptor Phidias fills the space at the Parthenon (448–432 BC) with a complex array of draped and undraped figures of deities, who appear in attitudes of sublime relaxation and elegance.

According to Vitruvius, the capital was invented by a bronze founder, Callimachus of Corinth, who took his inspiration from a basket of offerings that had been placed on a grave, with a flat tile on top to protect the goods.

Many fragments of these have outlived the buildings that they decorated and demonstrate a wealth of formal border designs of geometric scrolls, overlapping patterns and foliate motifs.

[45] In later Ionic architecture, there is greater diversity in the types and numbers of mouldings and decorations, particularly around doorways, where voluted brackets sometimes occur supporting an ornamental cornice over a door, such as that at the Erechtheion.

[41] Both images parallel the stylised depiction of the Gorgons on the black figure name vase decorated by the Nessos painter (c. 600 BC), with the face and shoulders turned frontally, and the legs in a running or kneeling position.

The eastern pediment shows a moment of stillness and "impending drama" before the beginning of a chariot race, the figures of Zeus and the competitors being severe and idealised representations of the human form.

[51] The reliefs and three-dimensional sculpture which adorned the frieze and pediments, respectively, of the Parthenon, are the lifelike products of the High Classical style (450–400 BC) and were created under the direction of the sculptor Phidias.

[52] The pedimental sculpture represents the Gods of Olympus, while the frieze shows the Panathenaic procession and ceremonial events that took place every four years to honour the titular Goddess of Athens.

[52] The frieze and remaining figures of the eastern pediment show a profound understanding of the human body, and how it varies depending upon its position and the stresses that action and emotion place upon it.

Benjamin Robert Haydon described the reclining figure of Dionysus as "the most heroic style of art, combined with all the essential detail of actual life".

The scene appears to have filled the space with figures carefully arranged to fit the slope and shape available, as with the earlier east pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympus.

[47] Hellenistic architectural sculpture (323–31 BC) was to become more flamboyant, both in the rendering of expression and motion, which is often emphasised by flowing draperies, the Nike Samothrace which decorated a monument in the shape of a ship being a well-known example.

The frieze represents the battle for supremacy of Gods and Titans, and employs many dramatic devices: frenzy, pathos and triumph, to convey the sense of conflict.

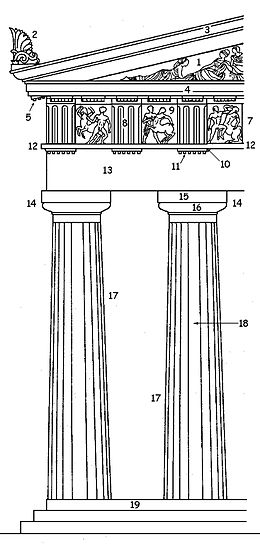

1. Tympanum , 2. Acroterium , 3. Sima 4. Cornice 5. Mutules 7. Frieze 8. Triglyph 9. Metope

10. Regula 11. Gutta 12. Taenia 13. Architrave 14. Capital 15. Abacus 16. Echinus 17. Column 18. Fluting 19. Stylobate

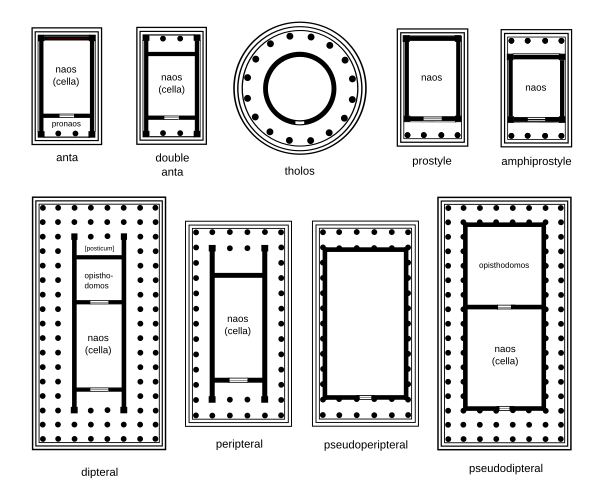

Top: 1. distyle in antis , 2. amphidistyle in antis , 3. tholos , 4. prostyle tetrastyle , 5. amphiprostyle tetrastyle ,

Bottom: 6. dipteral octastyle , 7. peripteral hexastyle , 8. pseudoperipteral hexastyle , 9. pseudodipteral octastyle