Greeks in Russia and Ukraine

Greeks have been present in what is now southern Russia from the 6th century BC; those settlers assimilated into the indigenous populations.

The area was vaguely described as the Hyperborea ("beyond the North wind") and its mythical inhabitants, the Hyperboreans, were said to have blissfully lived under eternal sunshine.

Medea was a princess of Colchis, modern western Georgia, and was entangled in the myth of Jason and the Golden Fleece.

Many Greeks remained in Crimea after the Bosporan kingdom fell to the Huns and the Goths, and Chersonesos became part of the Byzantine Empire.

[5][6] Relations with the people from the Kievan Rus principalities were stormy at first, leading to several short lived conflicts, but gradually raiding turned to trading and many also joined the Byzantine military, becoming its finest soldiers.

The post as Metropolitan bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church was, in fact, with few exceptions, held by a Byzantine Greek all the way to the 15th century.

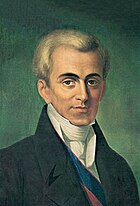

[6] There have been several notable Greeks from Russia like Ioannis Kapodistrias, diplomat of the Russian Empire who became the first head of state of Greece, and the painter Arkhip Kuindzhi.

In the early years after the October Revolution of 1917, there were contradictory trends in Soviet governmental policies towards ethnic Greeks.

Greeks engaged in trade or other occupations that marked them as class enemies of the Bolshevik government - who constituted a large part of the whole - were exposed to a hostile attitude.

[6] This was exacerbated due to the participation of a regiment from Greece, numbering 24,000 troops, in Crimea among the forces intervening on the White Russian side in the Civil War of 1919[7] About 50,000 Greeks emigrated between 1919 and 1924.

The Soviet administration established a Greek-Rumaiic theater, several magazines and newspapers and a number of Rumaiic language schools.

In the Πανσυνδεσμιακή Σύσκεψη (All-Union Conference) of 1926, organized by the Greek-Russian intelligentsia, it was decided that demotic should be the official language of the community.

At the time of the Moscow Trials and the purges targeting various groups and individuals who aroused Joseph Stalin's often unbased suspicions, policies towards ethnic Greeks became unequivocally harsh and hostile.

Kostoprav and many other Rumaiics and Urums were killed, and a large percentage of the population was detained and transported to Gulags or deported to remote parts of the Soviet Union.

In the immediate aftermath of the World War II German invasion of the Soviet Union, ethnic Greeks were included in the 1941–1942 "preventive" deportations of Soviet citizens of "enemy nationality", together with ethnic Germans, Finns, Romanians, Italians, and others - even though Greece fought on the Allied side.

(Some of these Greeks, known as Urums, spoke a variant of the Crimean Tatar language as the mother tongue they adopted during centuries of life in proximity to the Tartars).

Until recently, the ban on teaching Greek in Soviet schools meant that Pontian was spoken only in a domestic context.

In recent years, many Russian émigrés of Greek descent who had left in the early 1990s have returned to Russia, often with their Greece-born children.