Greenwich armour

The armoury was formed by imported master armourers hired by Henry VIII, initially including some from Italy and Flanders, as well as the Germans who dominated during most of the 16th century.

Jousting was a favourite pastime of Henry VIII (at dire cost to his health), and his daughter Elizabeth I made her Accession Day tilts a highlight of the court's calendar, focused on hyperbolic declarations of loyalty and devotion in the style of contemporary verse epics.

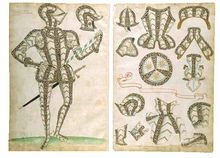

The book of Greenwich armour designs for 24 different gentlemen, known as the "Jacob Album" after its creator, includes many of the most important figures of the Elizabethan court.

By the mid-17th century, plate armour had adopted a stark and utilitarian form favoring thickness and protection (from the ever-more-powerful firearms which were redefining battle) over aesthetics and was generally only used by heavy cavalry; afterwards, it was to disappear more or less completely.

[2] The first Greenwich harnesses, created under Henry VIII, were typically of uniform colouration, either gilded or silvered all over and then etched with intricate motifs, often designed by Hans Holbein.

A good example of this early sort of Greenwich style is the harness which is thought to have belonged to Galiot de Genouillac, Constable of France, but was initially created for King Henry.

The armour, currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, has a specially designed corset built into the cuirass to support the weight of the burly king's large stomach.

Very similar in design, but ungilded, is another tournament harness made for Henry VIII which now resides at the Tower of London and which is famous for its large codpiece.

Older styles of armour-making, such as Maximilian and Gothic, emphasized the shaping of the metal itself, such as fluting and roping, to create artistic designs in the armour, rather than using colour.

A garniture would typically include a full plate harness plus an extra visor specially meant for tilting; a burgonet helmet which would be worn open-faced for a parade or ceremony, or with a removable "falling-buffe" visor for combat; a grandguard, which would reinforce the upper portion of the torso and neck for jousting; a passguard, which would reinforce the arm; and a manifer, a large gauntlet to protect the hand.

The Greenwich workshop continued producing armours into the reign of James I and Charles I, although the heyday of grand tournaments and exaggerated chivalric pageantry which characterized Elizabethan England had largely passed after the death of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales.

This transition can be seen in the styling of the post-Jacobean Greenwich armour; gilded decoration and etching is now absent, and the steel is no longer russeted, polished "white" or boldly colored in any other way but is uniformly a simple blue-gray shade.

Among them are Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester; William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke; Sir Thomas Bromley, Lord Chancellor of England; Sir Christopher Hatton, who succeeded Bromley as Lord Chancellor and was also rumored to be Queen Elizabeth's lover; Sir Henry Lee, Queen Elizabeth's first official jousting champion; and George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland, the Queen's second official champion and also an important naval commander who briefly captured Fort San Felipe del Morro.

Other notable figures whose suits of armour are displayed in the album are Thomas Sackville, 1st Earl of Dorset (then "Lord Buckhurst", which survives in the Wallace Collection in London), who served as Lord High Treasurer but is perhaps best known as the co-author of Gorboduc, one of the first tragedies written in blank verse, and Sir James Scudamore, a gentleman usher and tilting champion who was the basis for the character "Sir Scudamour" in The Fairie Queene by Edmund Spenser.

The complete garniture of George Clifford is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, along with the armours of Sir James Scudamore and Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke.

[3] When compared with extant examples of the armour to which they correspond, the drawings in Jacob Halder's album are nearly exact representations of the designs of the finished product.