Gregg Toland

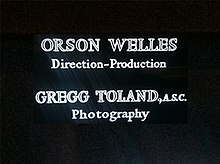

Gregg Wesley Toland (May 29, 1904 – September 28, 1948) was an American cinematographer known for his innovative use of techniques such as deep focus, examples of which can be found in his work on Orson Welles' Citizen Kane (1941), William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), and John Ford's The Grapes of Wrath, and The Long Voyage Home (both, 1940).

He is also known for his work as a director of photography for Wuthering Heights (1939), The Westerner (1940), Ball of Fire (1941), The Outlaw (1943), Song of the South (1946) and The Bishop's Wife (1947).

He worked with many of the leading directors of his era, including John Ford, Howard Hawks, Erich von Stroheim, King Vidor, Orson Welles and William Wyler.

Three feet from the lens, in the center of the foreground, was another face, and then, over a hundred yards away was the rear wall of the studio, showing telephone wires and architectural details.

[5] Some film historians believe Citizen Kane's visual brilliance was due primarily to Toland's contributions, rather than director Orson Welles'.

Nevertheless, the Welles movies that most resemble Citizen Kane (The Magnificent Ambersons, The Stranger, and Touch of Evil) were shot by Toland collaborators Stanley Cortez and Russell Metty (at RKO).

Apparently, Welles was unaware that one could achieve the effects optically on a film so he instructed the crew to dim the lights as they would have done on a theater production, which led to the unique dissolves.

However, the visuals were truly a collaboration, as Toland contributed great amounts of technical expertise that Welles needed so that he could achieve his vision.

Years later, Welles acknowledged: "Toland was advising him on camera placement and lighting effects secretly so the young director would not be embarrassed in front of the highly experienced crew.

Cinematographers before him used a shallow depth of field to separate the various planes on the screen, creating an impression of space as well as stressing what mattered in the frame by leaving the rest (the foreground or background) out of focus.

[citation needed] In Toland's lighting schemes, shadow became a much more compelling tool, both dramatically and pictorially, to separate the foreground from the background and so to create space within a two-dimensional frame while keeping all of the picture in focus.

[citation needed] For John Ford's The Long Voyage Home (1940), Toland leaned more heavily on back-projection to create his deep focus compositions, such as the shot of the island women singing to entice the men of the SS Glencairn.

[citation needed] Toland innovated extensively on Citizen Kane, creating deep focus on a sound-stage, collaborating with set designer Perry Ferguson so ceilings would be visible in the frame by stretching bleached muslin to stand in as a ceiling, allowing placement of the microphone closer to the action without being seen in frame.

Toland had worked closely with a Kodak representative during the stock's creation before its release in October 1938, and was one of the first cinematographers using it heavily on set.

Some of these shots were composited with an optical printer, a device which Dunn improved upon over the years, which explains why foreground and background are both in focus even though the lenses and film stock used in 1941 could not allow for such depth of field.

[17] The 2006 Los Angeles edition of CineGear assembled a distinguished panel composed of Owen Roizman, László Kovács, Daryn Okada, Rodrigo Prieto, Russell Carpenter, Dariusz Wolski and others.