Grey heron

[2] The grey heron was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.

[4] Four subspecies are recognised:[5] It is closely related and similar to the North American great blue heron (Ardea herodias), which differs in being larger, and having chestnut-brown flanks and thighs; and to the cocoi heron (Ardea cocoi) from South America, with which it forms a superspecies.

[12] The main call is a loud croaking "fraaank", but a variety of guttural and raucous noises are heard at the breeding colony.

A loud, harsh "schaah" is used by the male in driving other birds from the vicinity of the nest and a soft "gogogo" expresses anxiety, as when a predator is nearby or a human walks past the colony.

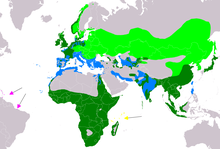

The range of the nominate subspecies A. c. cinerea extends to 70° N in Norway and 66°N in Sweden, but its northerly limit is around 60°N across the rest of Europe and Asia, as far eastwards as the Ural Mountains.

To the south, its range extends to northern Spain, France, central Italy, the Balkans, the Caucasus, Iraq, Iran, India, The Maldives and Myanmar (Burma).

[12] The grey heron is also known to be vagrant in the Caribbean, Bermuda, Iceland, Greenland, the Aleutian Islands, and Newfoundland, with a few confirmed sightings in other parts of North America including Nova Scotia and Nantucket.

Although most common in the lowlands, it also occurs in mountain tarns, lakes, reservoirs, rivers, marshes, ponds, ditches, flooded areas, coastal lagoons, estuaries, and the sea shore.

Breeding colonies are usually near feeding areas, but exceptionally may be up to eight kilometres (five miles) away, and birds sometimes forage as much as 20 km (12 mi) from the nesting site.

In spring, and occasionally in autumn, birds may soar high above the heronry and chase each other, undertake aerial manoeuvres or swoop down towards the ground.

The birds often perch in trees, but spend much time on the ground, striding about or standing still for long periods with an upright stance, often on a single leg.

[21] It may stand motionless in the shallows, or on a rock or sandbank beside the water, waiting for prey to come within striking distance.

[12] Small fish are swallowed head first, and larger prey and eels are carried to the shore where they are subdued by being beaten on the ground or stabbed by the bill.

[12] This species breeds in colonies known as heronries, usually in high trees close to lakes, the seashore, or other wetlands.

Other sites are sometimes chosen, and these include low trees and bushes, bramble patches, reed beds, heather clumps and cliff ledges.

When a bird arrives at the nest, a greeting ceremony occurs in which each partner raises and lowers its wings and plumes.

[23] Garden ponds stocked with ornamental fish are attractive to herons, and the easy prey may provide young birds with a learning opportunity on how to hunt.

[24] Herons have been observed visiting water enclosures in zoos, such as spaces for penguins, otters, pelicans, and seals, and taking food meant for the animals on display.

For example, in the 1970s, major Soviet experts considered the grey heron to be a harmful species, for example, for fish breeding reservoirs in Ukraine.

However, in some places, grey herons can serve as a breeding ground for the so-called ink sickness, or postodiplostomosis, a dangerous disease of young cyprinids.

In addition, large colonies of grey herons can have a significant impact on soil biogeochemistry and vegetation.

For example, a heron colony in one study site located near the southern edge of the Republic of Tatarstan on a peninsula formed by the confluence of the Volga, the largest and longest river in Europe, and its largest tributary, the Kama, on the banks of the smaller river Myosha (a tributary of the Kama); after settling around 2006, it expanded for 15 years, leading to the intensive deposition of nutrients with faeces, food remains and feathers thereby considerably altering the local soil biogeochemistry.

[29] Thus, lower pH levels around 4.5, 10- and 2-fold higher concentrations of phosphorus and nitrogen, as well as 1.2-fold discrepancies in K, Li, Mn, Zn and Co, respectively, compared to the surrounding control forest area could be observed.

[30][31] The eggs and young are more vulnerable; the adult birds do not usually leave the nest unattended, but may be lured away by marauding crows or kites.

[33] A study performed by Sitko and Heneberg in the Czech Republic between 1962 and 2013 suggested that Central European grey herons host 29 species of parasitic worms.

Of the digenean flatworms found in Central European grey herons, 52% of the species likely infected their definitive hosts outside Central Europe itself, in the premigratory, migratory, or wintering quarters, despite the fact that a substantial proportion of grey herons do not migrate to the south.

[34] Bennu, an ancient Egyptian deity associated with the sun, creation, and rebirth, was depicted as a heron in New Kingdom artwork.

[35] In ancient Rome, the heron was a bird of divination that gave an augury (sign of a coming event) by its call, like the raven, stork, and owl.