Grimace scale

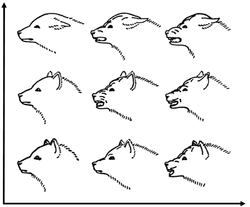

Observers score the presence or prominence of "facial action units" (FAU), e.g. Orbital Tightening, Nose Bulge, Ear Position and Whisker Change.

[1] For mice at least, the GS has been shown to be a highly accurate, repeatable and reliable means of assessing pain requiring only a short period of training for the observer.

[2][3] Across species, GS are proven to have high accuracy and reliability, and are considered useful for indicating both procedural and postoperative pain, and for assessing the efficacy of analgesics.

The biologist Charles Darwin considered that non-human animals exhibit similar facial expressions to emotional states as do humans.

In 2010, a team of researchers successfully developed[9] the first method to assess pain using changes in facial expression in any non-human animal species.

Observers score the presence and extent of "facial action units" (FAU), e.g. Orbital Tightening, Nose Bulge, Ear Position and Whisker Change.

In mice, the GS offers a means of assessing post-operative pain that is as effective as manual behavioural-based scoring, without the limitations of such approaches.

The effectiveness of the GS at identifying pain was compared with a traditional welfare scoring system based on behavioural, clinical and procedure-specific criteria.

[14] The mouse GS has been shown to be a highly accurate, repeatable and reliable means of assessing pain, requiring only a short period of training for the observer.

[2] Assessment approaches that train deep neural networks to detect pain and no-pain images of mice may further speed up MGS scoring, with an accuracy of 94%.

[16] There are interactions between the sex and strain of mice in their GS and also the method that is used to collect the data (i.e. real-time or post hoc), which indicates scorers need to consider these factors.

[2] It is important to establish whether methods of pain assessment in laboratory animals are influenced by other factors, especially those which are a normal part of routine procedures or husbandry.

[26] As with mice, studies have examined the extent of agreement in assessing pain between rat GS and the use of von Frey filaments.

[28] For rats, software (Rodent Face Finder) has been developed which successfully automates the most labour-intensive step in the process of quantifying the GS, i.e. frame-grabbing individual face-containing frames from digital video, which is hindered by animals not looking directly at the camera or poor images due to motion blurring.

The pain face here involves similar facial expressions described for the HGS; low and/or asymmetrical ears, an angled appearance of the eyes, a withdrawn and/or tense stare, medio-laterally dilated nostrils and tension of the lips, chin and certain mimetic muscles and can potentially be incorporated to improve existing pain evaluation tools.

[38] A complete GS (Feline Grimace Scale - FGS) for cats was published in 2019 to detect naturally-occurring acute pain.