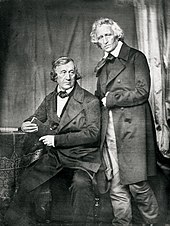

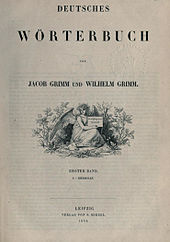

Brothers Grimm

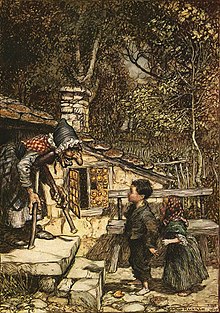

The brothers are among the best-known storytellers of folktales, popularizing stories such as "Cinderella" ("Aschenputtel"), "The Frog Prince" ("Der Froschkönig"), "Hansel and Gretel" ("Hänsel und Gretel"), "Town Musicians of Bremen" ("Die Bremer Stadtmusikanten"), "Little Red Riding Hood" ("Rotkäppchen"), "Rapunzel", "Rumpelstiltskin" ("Rumpelstilzchen"), "Sleeping Beauty" ("Dornröschen"), and "Snow White" ("Schneewittchen").

The rise of Romanticism in 19th-century Europe revived interest in traditional folk stories, which to the Brothers Grimm represented a pure form of national literature and culture.

With the goal of researching a scholarly treatise on folktales, they established a methodology for collecting and recording folk stories that became the basis for folklore studies.

Dorothea was forced to relinquish the brothers' servants and large house, depending on financial support from her father and sister, who was then the first lady-in-waiting at the court of William I, Elector of Hesse.

The two brothers differed in temperament—Jacob was introspective and Wilhelm was outgoing (although he often suffered from ill health)—but shared a strong work ethic and excelled in their studies.

Their poverty kept them from student activities or university social life, but their outsider status worked in their favor and they pursued their studies with extra vigor.

[5] Inspired by their law professor, Friedrich von Savigny, who awakened in them an interest in history and philology, the brothers studied medieval German literature.

On his return to Marburg he was forced to abandon his studies to support the family, whose poverty was so extreme that food was often scarce, and take a job with the Hessian War Commission.

[9] According to Zipes, at this point "the Grimms were unable to devote all their energies to their research and did not have a clear idea about the significance of collecting folk tales in this initial phase.

[12] In 1840, Savigny and Bettina von Arnim appealed successfully to Frederick William IV of Prussia on behalf of the brothers, who were offered posts at the University of Berlin.

"[12] The rise of romanticism, romantic nationalism, and trends in valuing popular culture in the early 19th century revived interest in fairy tales, which had declined since their late 17th-century peak.

Scholar Lydie Jean says that Perrault created a myth that his tales came from the common people and reflected existing folklore to justify including them—even though many of them were original.

[15] The brothers were directly influenced by Brentano and von Arnim, who edited and adapted the folk songs of Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy's Magic Horn or cornucopia).

Wilhelm's wife, Henriette Dorothea (Dortchen) Wild, and her family, with their nursery maid, told the brothers some of the more well-known tales, such as "Hansel and Gretel" and "Sleeping Beauty".

[25] According to scholars such as Tatar and Ruth Bottigheimer, some of the tales probably originated in written form during the medieval period with writers such as Straparola and Boccaccio, but were modified in the 17th century and again rewritten by the Grimms.

He made the tales stylistically similar, added dialogue, removed pieces "that might detract from a rustic tone", improved the plots, and incorporated psychological motifs.

[19] Over the years, Wilhelm worked extensively on the prose; he expanded and added detail to the stories to the point that many of them grew to twice the length they had in the earliest published editions.

[31] Another story, "The Goose Girl", has a servant stripped naked and pushed into a barrel "studded with sharp nails" pointing inward and then rolled down the street.

[41] The brothers strongly believed that the dream of national unity and independence relied on a full knowledge of the cultural past that was reflected in folklore.

Its sales generated a mini-industry of critiques, which analyzed the tales' folkloric content in the context of literary history, socialism, and psychological elements often along Freudian and Jungian lines.

[50] In Nazi Germany the Grimms' stories were used to foster nationalism as well as to promote antisemitic sentiments in an increasingly hostile time for Jewish people.

The Nazi Party decreed that every household should own a copy of Kinder- und Hausmärchen; later, officials of Allied-occupied Germany banned the book for a period.

According to Robert Weinberg, Professor of Jewish History at Swarthmore College, “the accusation that Jews murder Christians, particularly young boys and girls, for ritual purposes has a long and lurid lineage that dates back to the Middle Ages.

The accusation of ritual murder emerged in England in the mid-twelfth century with the charge that Jews had killed a Christian youth in order to mock the Passion of Christ.

[58] At this time, European Jews were often hunted down and murdered when an Aryan child went missing and stories abounded that the victims, when found, would bleed in the presence of their Jewish killers.

[13] In film, the Cinderella motif, the story of a poor girl finding love and success, has been repeated in movies such as Pretty Woman, Ever After, Maid in Manhattan, and Ella Enchanted.

[48] Dégh writes that some educators, in the belief that children should be shielded from cruelty of any form, believe that stories with a happy ending are fine to teach, whereas those that are darker, particularly the legends, might pose more harm.

[60] More popular stories, such as "Hansel and Gretel" and "Little Red Riding Hood", have become staples of modern childhood, presented in coloring books, puppet shows, and cartoons.

The film The Brothers Grimm imagines them as con artists exploiting superstitious German peasants until they are asked to confront a genuine fairy-tale curse that calls them to finally be heroes.

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were, in fact, chosen by Mother Goose and others to tell fairy tales so that they might give hope to the human race.