Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram

[1] The site has 40 ancient monuments and Hindu temples,[4] including one of the largest open-air rock reliefs in the world: the Descent of the Ganges or Arjuna's Penance.

[8] The Mahabalipuram temples are in the southeastern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, about 60 kilometres (37 mi) southwest of Chennai on the Coromandel Coast.

[9] Mahabalipuram is known by several names, including Mamallapuram; Mamalla means "Great Wrestler", and refers to the 7th-century king Narasimha Varman I.

[11] According to Nagaswamy, the name is derived from the Tamil word mallal (prosperity) and reflects its being an ancient economic center for South India and Southeast Asia.

[12][note 1] This theory is partially supported by an 8th-century Tamil text by the early Bhakti movement poet Thirumangai Alvar, where Mamallapuram is called "Kadal Mallai".

[16][17][note 2] The Tamil Nadu government adopted Mamallapuram as the official name of the site and township in 1957, and declared the monuments and coastal region a special tourism area and health resort in 1964.

[18] Although the ancient history of Mahabalipuram is unclear, numismatic and epigraphical evidence and its temples suggest that it was a significant location before the monuments were built.

[16][17] In his Avantisundari Katha, the 7th–8th century Sanskrit scholar Daṇḍin (who lived in Tamil Nadu and was associated with the Pallava court) praised artists for their repair of a Vishnu sculpture at Mamallapuram.

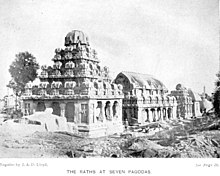

[19] When Marco Polo (1271-1295 CE) arrived in India on his way back to Venice from Southeast Asia, he mentioned (but did not visit) "Seven Pagodas" and the name became associated with the shore temples of Mahabalipuram in publications by European merchants centuries later.

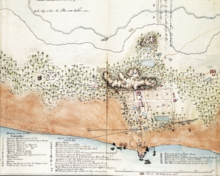

It appeared in Abraham Cresques' 1375 Catalan Atlas as "Setemelti" and "Santhome", a crude map of Asia but accurate in the relative positions of the two ports; the former is Mamallapuram and the latter Mylapore.

[21][note 3] Venetian traveler Gasparo Balbi mentioned the "Seven Pagodas" and "Eight Pleasant Hillocks" in 1582, which Nagaswamy suggests refers to the monuments.

This has revealed ruins of fallen walls, a large number of rectangular blocks and other structures parallel to the shore, and the forty surviving monuments.

[21] According to Anthony Hamilton's 1727 "New Account of the East Indies", the site was a pilgrimage center and its outside sculpture was "obscene, lewd" as performance in Drury Lane.

[26] Chambers interviewed local residents and linked the monumental art he saw to Hindu texts, calling it remarkable and expressive in narrative detail.

[27] Nineteenth-century reports note local mentions of "gilt tops of many pagodas" in the surf at sunrise, which elders talked about but could no longer be seen.

[29] After Indian independence, the Tamil Nadu government developed the Mamallapuram monuments and coastal region as an archaeological, tourism and pilgrimage site by improving the road network and town infrastructure.

[30] Mamallapuram became prominent during the Pallava-era reign of Simhavishnu during the late 6th century, a period of political competition with the Pandyas, the Cheras and spiritual ferment with the rise of 6th- to 8th-century Bhakti movement poet-scholars: the Vaishnava Alvars and the Shaiva Nayanars.

[31][3] Mid-20th-century archaeologist A. H. Longhurst described Pallava architecture, including those found at Mahabalipuram, into four chronological styles: Mahendra (610-640), Mamalla (640-670, under Narsimha Varman I), Rajasimha (674-800) and Nandivarman (800-900).

[34] Other, such as Nagaswamy in 1962, have said that King Rajasimha (690-728) was the probable patron of many monuments; many temple inscriptions contain one of his names and his distinctive Grantha and ornate Nāgarī scripts.

According to Mate and other scholars, the inscription implies that the Tamil people had a temple-construction tradition based on the mentioned materials which predated the 6th century.

The reliefs, sculptures and architecture incorporate Shaivism, Vaishnavism and Shaktism, with each monument dedicated to a deity or a character in Hindu mythology.

[41][42][43] The monuments are a source of many 7th- and 8th-century Sanskrit inscriptions, providing insight into medieval South Indian history, culture, government and religion.

[64] Segments of the caves indicate that artisans worked with architects to mark off the colonnade, cutting deep grooves into the rock to create rough-hewn protuberances with margins.

[65] The northern panel of the cave's inner wall narrates the Varaha legend, where the man-boar avatar of Vishnu rescues Bhūmi from the waters of Patala.

In the central shrine is a large rock relief of Somaskanda, with Shiva seated in a Sukhasana (cross-legged) yoga posture and Parvati next to him with the infant Skanda.

The temple is steeper and taller than the Arjuna and Dharmaraja rathas, with a similar design in which the superstructure repeats the lower level in a shrinking square form.

Twentieth-century restoration efforts replaced them in accordance with the inscriptions, descriptions of the temple in medieval texts and excavations of layers which confirmed that Nandi bulls were seated along its periphery.

The absence of a boar from the entire panel makes it doubtful that it is single story, although scenes of Arjuna's penance and the descent of the Ganges are affirmed.

"[108] Krishna's Butterball (also known as Vaan Irai Kal)[114]) is a gigantic granite boulder resting on a short incline in the historical coastal resort town of Mamallapuram in Tamil Nadu state of India.

[118] The Archaeological Survey of India has laid the lawns and pathways around the monuments, and the Housing and Urban Development Corporation (HUDCO) has designed parks on both sides of the roads leading to the Shore Temple and the Five Rathas.