Guide number

The guide number system, which manufacturers adopted after consistent-performing mass-produced flashbulbs became available in the late 1930s, has become nearly superfluous due to the ubiquity of electronic photoflash devices featuring variable flash output and automatic exposure control, as well as digital cameras, which make it trivially easy, quick, and inexpensive to adjust exposures and try again.

[3] Still, guide numbers in combination with flash devices set to manual exposure mode remain valuable in a variety of circumstances, such as when unusual or exacting results are required and when shooting non-average scenery.

[note 3] Since guide numbers are so familiar to photographers, they are near-universally used by manufacturers of on-camera flash devices to advertise their products' relative capability.

Throughout most of the world where the metric system (SI) is observed, guide numbers are expressed as a unitless numeric value like 34, even though they are technically a composite unit of measure that is a two-factor product: f‑number⋅meters.

When comparing or shopping for flash devices, it is important to ensure that the guide numbers are given in the same ISO sensitivity, are for the same coverage angle, and reduce to the same unit of distance (meters or feet).

When these three variables have been normalized, guide numbers can serve as a relative measure of intrinsic illuminating energy rather than an inconstant metric for calculating exposures.

Nevertheless, for those who want to master the math, guide numbers diminish from their full-power ratings as the square root of their fractional setting per the following formula: The following is a step-by-step example of using the above formula: Suppose your full-power guide number is 48 (it is irrelevant if it is scaled for meters or feet for this purpose) and the flash device is set to 1/16 th power.

Manufacturers' advertising practices vary as to the angle of coverage underlying their guide number ratings, in large part because some flash devices can be zoomed whereas others are fixed.

[note 7] Unfortunately, the optics of flash heads are complex; each manufacture's designs not only have illumination areas that are slightly different, but are the product of differing relative proportions of transmission, diffusion, reflection, and refraction among their optical elements (flash tube, reflector, Fresnel lens, and add-on wide-angle adapter).

The below table illustrates the variation in guide numbers depending on zoom level for some select, relatively high-power zoom-capable flash devices.

This photo was shot in fair quality air at ISO 12,800 using a modestly powerful camera-mounted flash, yielding a high guide number of 438 (m) / 1438 (ft).

When shot at f/1.8 to favor distance, the utility pole marked by the arrow would be properly illuminated were it not for haze glare, which fogged the image and diminished brightness.Among other variables like illumination angle (for devices with zoomable flash heads) and power setting, guide numbers are a function of the ISO sensitivity (film speed or ISO setting on a digital camera).

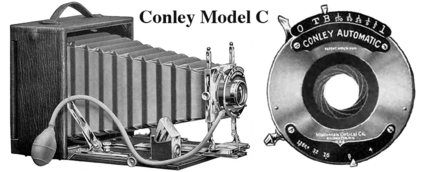

Today, the state of the art has advanced so that with the exception of the least expensive models, virtually all modern on-camera flash devices feature either a built-in mechanical circular calculator (such as shown in the photo at the top of this article) or—more modern yet—a digital display; both methods automatically calculate the effect ISO settings have on f‑stop and distance (guide number).

Such features make it exceedingly easy to find a suitable combination of f‑stop and distance so photographers seldom need to concern themselves with the mathematical details underlying how their flash devices' guide number changes with different ISO sensitivities.

Note that the extremely high guide numbers shown in the right-hand portion of the table have a limited real-world ability to extend flash distances.

ISO settings like 102,400 can yield guide numbers in excess of 1220 (m) / 4000 (ft) that seldom if ever permit extremely long-range flash photography due to particulates and aerosols typically present in outside air that fog images with haze glare and attenuate the reach of the light.

Except in unusual atmospheric conditions, extraordinarily large guide numbers will produce suitable results only by either positioning the flash device off-axis from the camera by a fair distance or by shooting at the smallest apertures.

Some modern flash devices can even detect when color-correction gels have been attached and automatically compensate for their effect on guide numbers.

Unless a hot shoe-mounted electronic flash device's power can be controlled by a camera via through-the-lens metering (TTL), guide numbers must be manually compensated for the effect of on-lens filters.

After the flash has extinguished, longer shutter speeds will only increase the contribution from continuous ambient light, which can lead to ghosting with moving subjects.

[8] With peak powers often between one and two million lumens, many young baby boomers chased after fairylike retinal bleached spots (a symptom of flash blindness) for minutes after having their pictures taken at close distance with flashbulbs of the era.

So long as one used flashbulbs with leaf shutter-type cameras, faster exposures and larger apertures could be used to minimize motion blur or reduce depth of field at the expense of guide number.

Cameras with focal-plane shutters—even if they had PC connectors with X, F, M, or S-sync delays ("xenon sync" with zero delay and flashbulbs with peak delays of 5, 20, and 30 ms)—could not be used at speeds that attenuated guide numbers with most types of flashbulbs because their light curves were characterized by rapid rise and fall rates; the second shutter curtain would begin wiping shut during a period of rapid change in scene illuminance, causing uneven exposure across the image area that varied in nature depending on exposure duration and the type of bulb.

When filling in shadows outdoors, powerful flash devices (those with inherently greater guide numbers when compared at the same ISO sensitivity and coverage angle) can be useful because they permit photographers to increase the maximum flash-to-subject distance, such as when taking group photos.

[9][10][11] This compelling new way of easily and accurately calculating photoflash exposures was quickly adopted by manufacturers of a wide variety of photographic equipment, including flashbulbs, film, cameras, and flashguns.

Shortly later, in 1939, General Electric under their MAZDA brand introduced their very successful, golf ball-size, wire-filled, bayonet-base, Midget No. 5.

[note 13] Prior to GE's inverse of the squares innovation, photographers and publications—via tedious trial and error with different flashbulbs and reflectors—generated tables providing a large number of aperture-distance combinations.

For instance, a 1940 edition (written too late to incorporate guide numbers) of the Complete Introduction to Photography by the Journal of the Photographic Society of America featured an exposure table for foil-filled flashbulbs, which is shown below.

For end users, obtaining proper exposures with flashbulbs was an error-prone effort as they mentally interpolated between distances and f‑stop combinations that weren't very accurate in the first place.

[16] When utilizing fill flash, where balancing flash and continuous light can be difficult, the following four derivatives of this continuous-light exposure equation can be useful: For any combination of lighting, film, and camera settings that conforms to one of the above five equations, a proper luminous exposure is calculated as follows: Note that Kodak's exposure guidelines—for photographs taken in typical settings without the benefit of incident-light meters—are for pictures shot during a broad portion of the day with even some light haze in the sky; this is half as bright as the clear-sky, near-noon, open-area, "sunny f/16 rule", which is EV 15 at ISO 100, or 81,900 lux.

This photo was shot in fair quality air at ISO 12,800 using a modestly powerful camera-mounted flash, yielding a high guide number of 438 (m) / 1438 (ft) . When shot at f /1.8 to favor distance, the utility pole marked by the arrow would be properly illuminated were it not for haze glare, which fogged the image and diminished brightness.