Guillotine

The blade is then released, swiftly and forcefully decapitating the victim with a single, clean pass; the head falls into a basket or other receptacle below.

[3] The design of the guillotine was intended to make capital punishment more reliable and less painful in accordance with new Enlightenment ideas of human rights.

Prior to use of the guillotine, France had inflicted manual beheading and a variety of methods of execution, many of which were more gruesome and required a high level of precision and skill to carry out successfully.

The blade was an axe head weighing 3.5 kg (7.7 lb), attached to the bottom of a massive wooden block that slid up and down in grooves in the uprights.

A Hans Weiditz (1495–1537) woodcut illustration from the 1532 edition of Petrarch's De remediis utriusque fortunae, or "Remedies for Both Good and Bad Fortune" shows a device similar to the Halifax Gibbet in the background being used for an execution.

However, it was later named after French physician and Freemason Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, who proposed on 10 October 1789 the use of a special device to carry out executions in France in a more humane manner.

A death penalty opponent, he was displeased with the breaking wheel and other common, more grisly methods of execution and sought to persuade Louis XVI of France to implement a less painful alternative.

According to the memoir of the French executioner Charles-Henri Sanson, Louis XVI suggested the use of a straight, angled blade instead of a curved one.

[12] On 10 October 1789, physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin proposed to the National Assembly that capital punishment should always take the form of decapitation "by means of a simple mechanism".

[14] In 1791, as the French Revolution progressed, the National Assembly researched a new method to be used on all condemned people regardless of class, consistent with the idea that the purpose of capital punishment was simply to end life rather than to inflict unnecessary pain.

The group was influenced by beheading devices used elsewhere in Europe, such as the Italian Mannaia (or Mannaja, which had been used since Roman times[citation needed]), the Scottish Maiden, and the Halifax Gibbet (3.5 kg).

[14] Laquiante, an officer of the Strasbourg criminal court,[16] designed a beheading machine and employed Tobias Schmidt, a German engineer and harpsichord maker, to construct a prototype.

The machine was judged successful because it was considered a humane form of execution in contrast with more cruel methods used in the pre-revolutionary Ancien Régime.

The revolutionary radicals hanged officials and aristocrats from street lanterns and also employed more gruesome methods of execution, such as the wheel or burning at the stake.

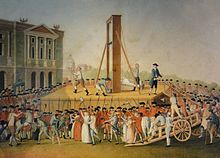

For a time, executions by guillotine were a popular form of entertainment that attracted great crowds of spectators, with vendors selling programs listing the names of the condemned.

[26] The Parisian sans-culottes, then the popular public face of lower-class patriotic radicalism, thus considered the guillotine a positive force for revolutionary progress.

The “hysterical behavior” by spectators was so scandalous that French president Albert Lebrun immediately banned all future public executions.

[31] In South America, the guillotine was only used in French Guiana, where about 150 people were beheaded between 1850 and 1945: most of them were convicts exiled from France and incarcerated within the "bagne", or penal colonies.

In Germany, the guillotine is known as Fallbeil ("falling axe") or Köpfmaschine ("beheading machine") and was used in various German states from the 19th century onwards,[citation needed] becoming the preferred method of execution in Napoleonic times in many parts of the country.

The guillotine, axe[32] and the firing squad were the legal methods of execution during the era of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the Weimar Republic (1919–1933).

Officials could also conduct multiple executions faster, thanks to a more effective blade recovery system and the eventual removal of the tilting board (bascule).

The Nazi government also guillotined Sophie Scholl, who was convicted of high treason after distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets at the University of Munich with her brother Hans, and other members of the German student resistance group, the White Rose.

Certain eyewitness accounts of guillotine executions suggest anecdotally that awareness may persist momentarily after decapitation, although there is no scientific consensus on the matter.

Gabriel Beaurieux, a physician who observed the head of executed prisoner Henri Languille, wrote on 28 June 1905: Here, then, is what I was able to note immediately after the decapitation: the eyelids and lips of the guillotined man worked in irregularly rhythmic contractions for about five or six seconds.

I saw the eyelids slowly lift up, without any spasmodic contractions – I insist advisedly on this peculiarity – but with an even movement, quite distinct and normal, such as happens in everyday life, with people awakened or torn from their thoughts.

It was at that point that I called out again and, once more, without any spasm, slowly, the eyelids lifted and undeniably living eyes fixed themselves on mine with perhaps even more penetration than the first time.