Guinea-Bissau War of Independence

However, the mainland was not fully "pacified" until the late 1930s, by which time the Portuguese regime of António de Oliveira Salazar was preoccupied with the development of its Angolan and Mozambican colonies.

[2] In the phrase of Patrick Chabal, Guinea was "the smallest and most backward of the Portuguese colonies", partly due to its inhospitable climate and apparent dearth of natural and mineral resources.

[2] In its first three years, PAIGC was preoccupied with mostly fruitless exercises in constitutional-legal agitation, concentrated in Bissau and other major cities and sometimes involving collaboration with local trade unions.

[2][11] The massacre led PAIGC to rethink its policies: in the aftermath, it reiterated its commitment to national liberation, but with a new emphasis on the political mobilisation of the rural peasantry.

At the start of hostilities the Portuguese had only two infantry companies in Guinea Bissau and these concentrated in the main towns, giving the insurgents free rein in the countryside.

[9] However, the movement was "well trained, well led, and well equipped", and its guerrilla campaign benefitted both from the terrain – its forces operated primarily from Guinea's dense jungles – and from external support.

[2] Senegalese President Léopold Sédar Senghor was generally pro-Western and he cooperated closely with Portuguese leaders in attempting to broker a political solution to the conflict.

[18][19] A Marxist organisation operating at the height of the Cold War, it was also supported, from the early 1960s, by socialist states further afield, including the People's Republic of China, the Soviet Union, and Czechoslovakia.

On a monthly basis, materiel was trucked from Koundara, Guinea-Conakry into Senegalese towns, including Vélingara, where pro-PAIGC forces maintained a warehouse, and then was transported across the border on foot.

You, who continue in the colonial army: to take part in crimes against our people: to contribute to ruining your country… ONLY FOR THE PLEASURE OF THE MONEY-GRABBERS OF YOUR COUNTRY The "Africanization" of the war effort by Portugal, also pursued in the Angolan and Mozambican theatres, proceeded with particular speed in Guinea, particularly after General Spínola's appointment.

The Special Marines (Fuzileiros Especiais Africanos) were created in 1970 and by 1974 numbered 160 men in two detachments;[30] they supplemented other Portuguese elite units conducting amphibious operations in the riverine areas of Guinea which attempted to interdict and destroy guerrilla forces and supplies.

[2] By July 1963, PAIGC had consolidated its military position in the southern littoral, and had also gained "a tenuous foothold" in the Mansôa–Mansaba–Oio triangle, north of the Geba estuary.

By this time, the PAIGC, led by Amílcar Cabral, began openly receiving military support from the Soviet Union, China, and Cuba.

Defensive operations, where soldiers were dispersed in small numbers to guard critical buildings, farms, or infrastructure were particularly devastating to the regular Portuguese infantry, who became vulnerable to guerrilla attacks outside of populated areas by the forces of the PAIGC.

[34] In order to maintain the economy in the liberated territories, the PAIGC was compelled at an early stage to establish its own Marxist administrative and governmental bureaucracy, which organized agricultural production, educated farm workers on protecting crops from destruction from government attacks, and opened collective armazéns do povo (people's stores) to supply urgently needed tools and supplies in exchange for agricultural produce.

General Spínola instituted a series of civil and military reforms, intended to first contain, then roll back the PAIGC and its control of much of the rural portion of Portuguese Guinea.

This included a 'hearts and minds' propaganda campaign designed to win the trust of the indigenous population, an effort to eliminate some of the discriminatory practices against native Guineans, a massive construction campaign for public works including new schools, hospitals, improved telecommunications and road networks, and a large increase in recruitment of native Guineans into the Portuguese armed forces serving in Guinea as part of an Africanisation strategy.

Warned by the peasants or by their own reconnaissance patrols, the PAIGC pulled back, loosely encircled the Portuguese, and launched night attacks to break up the column.

Military tactical reforms by Portuguese commanders included new naval amphibious operations to overcome some of the mobility problems inherent in the underdeveloped and marshy areas of the country.

At this time Portuguese forces also adopted unorthodox means of countering the insurgents, including attacks on the political structure of the nationalist movement.

In 1970 the Portuguese Air Force (FAP) began to use weapons similar to those the US was using in the Vietnam War: napalm and defoliants in order to find the insurgents or at least deny them the cover and concealment needed for rebel ambushes.

After 1968 PAIGC forces were increasingly supplied with modern Soviet weapons and equipment, most notably SA-7 rocket launchers and radar-controlled AA cannons.

[35][36] By 1970 the PAIGC even had candidates training in the Soviet Union, learning to fly MIGs and to operate Soviet-supplied amphibious assault crafts and APCs.

[9] Rather than disabling the group, the assassination of PAIGC's leader was followed by some of its most ambitious offensives, as it destroyed or took over key Portuguese positions in the north and on the southern border.

[2][9][27] As PAIGC deployed its new ground-to-air missiles, as well as new large-caliber mortars and rockets (reportedly from Soviet-bloc suppliers), the war "increasingly took on a 'conventional' rather than guerrilla character".

[27] On 23–24 September 1973, the People's National Assembly (Assembleia Nacional Popular de Guiné) met in Madina do Boé, near the border with Guinea-Conakry, and declared the independence of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau.

The war in Guinea-Bissau has been viewed as a factor which contributed to the coup and revolution: its status as "the most intense, destructive, and materially pointless" of the three Portuguese wars in Africa rendered it an embarrassment to the outgoing regime;[9] and the coup was organised by the left-wing Armed Forces Movement (Movimento das Forças Armadas), the core of which "took shape" first among military officers in Guinea-Bissau.

[9]According to Basil Davidson, a de facto ceasefire had already obtained in Guinea-Bissau since the Carnation Revolution, disturbed only once by a mild exchange of gunfire on 27 May, which had been precipitated by "a mutual confusion".

Historian Norrie McQueen notes that the accord and its implementation preserved an ambiguity with respect to the legal status of the withdrawal – that is, as to whether it constituted a negotiated transfer of power, or a belated recognition of the 1973 declaration of independence.

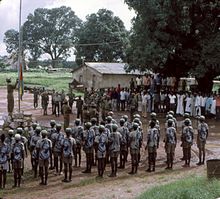

[49] Indigenous troops who had served with the Portuguese Army were given the choice of either returning home with their families while receiving full pay until the end of December 1974, or of joining the PAIGC military.