Gundestrup cauldron

It was found dismantled, with the other pieces stacked inside the base, in 1891, in a peat bog near the hamlet of Gundestrup in the Aars parish of Himmerland, Denmark (56°49′N 9°33′E / 56.817°N 9.550°E / 56.817; 9.550).

[9][3] While the vessel was found in Denmark, it was probably not made there or nearby; it includes elements of Gaulish and Thracian origin in the workmanship, metallurgy, and imagery.

[10][3] Hospitality on a large scale was probably an obligation for Celtic elites, and although cauldrons were therefore an important item of prestige metalwork, they are usually much plainer and smaller than this.

[1][2][6][7] In addition, there is a piece of iron from a ring originally placed inside the silver tubes along the rim of the cauldron.

The Gundestrup cauldron is composed almost entirely of silver, but there is also a substantial amount of gold for the gilding, tin for the solder and glass for the figures' eyes.

According to experimental evidence, the materials for the vessel were not added at the same time, so the cauldron can be considered as the work of artisans over a span of several hundred years.

[1][2] Specifically, the circular "base plate" may have originated as a phalera, and it is commonly thought to have been positioned in the bottom of the bowl as a late addition, soldered in to repair a hole.

[1][2] Finally, the glass inlays of the Gundestrup cauldron have been determined through the use of X-ray fluorescence radiation to be of a soda-lime type composition.

The glass contained elements that can be attributed to calcareous sand and mineral soda, typical of the east coast of the Mediterranean region.

Using scanning electron microscopy, Benner Larson has identified 15 different punches used on the plates, falling into three distinct tool sets.

[1][2] The silverworking techniques used in the cauldron are unknown from the Celtic world, but are consistent with the renowned Thracian sheet-silver tradition.

[6][7] Taylor and Bergquist have postulated that the Celtic tribe known as the Scordisci commissioned the cauldron from native Thracian silversmiths.

According to classical historians, the Cimbri, a Teutonic tribe, went south from the lower Elbe region and attacked the Scordisci in 118 BC.

After withstanding several defeats at the hands of the Romans, the Cimbri retreated north, possibly taking with them this cauldron to settle in Himmerland, where the vessel was found.

[6][7] According to Olmsted (2001) the art style of the Gundestrup cauldron is that utilized in Armorican coinage dating to 75–55 BCE, as exemplified in the billon coins of the Coriosolites.

In the end, based on accelerator datings from beeswax found on the back of the plates, Nielsen concludes that the vessel was created within the Roman Iron Age.

The head of the bull rises entirely clear of the plate, and the medallion is considered the most accomplished part of the cauldron in technical and artistic terms.

[31] Much less controversially, there are clear parallels between details of the figures and Iron Age Celtic artifacts excavated by archaeology.

Scholars are mostly content to regard the former as motifs borrowed purely for their visual appeal, without carrying over anything much of their original meaning, but despite the distance some have attempted to relate the latter to wider traditions remaining from Proto-Indo-European religion.

The carnyx war horn was known from Roman descriptions of the Celts in battle and Trajan's Column, and a few pieces are known from archaeology, their number greatly increased by finds at Tintignac in France in 2004.

Another detail that is easily matched to archaeology is the torc worn by several figures, clearly of the "buffer" type, a fairly common Celtic artefact found in Western Europe, most often France, from the period the cauldron is thought to have been made.

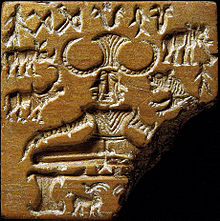

On several of the exterior plates the large heads, probably of deities, in the centre of the exterior panels, have small arms and hands, either each grasping an animal or human in a version of the common Master of Animals motif, or held up empty at the side of the head in a way suggesting inspiration from this motif.

[7] Because of the double-headed wolfish monster attacking the two small figures of fallen men on plate b, parallels can be drawn to the Welsh character Manawydan or the Irish Manannán, a god of the sea and the Otherworld.

Olmsted[16] interprets the scene on plate C as a Gaulish version of the Irish Táin incidents where Cu Chulainn kicks in the Morrigan's ribs when she comes at him as an eel and then confronts Fergus with his broken chariot wheel.

[16] Olmsted (1979) interprets the scene with warriors on the lower part of Plate E as a Gaulish version of the "Aided Fraich" episode of the Táin where Fraich and his men leap over the fallen tree, and then Fraech wrestles with his father Cu Chulainn and is drowned by him, while his magic horn blowers play "the music of sleeping" against Cu Chulainn.

In addition, he points to the similarity between the female figure of plate B and the Hindu goddess Lakshmi, whose depictions are often accompanied by elephants.