Gunpowder Plot

Catesby is suspected by historians to have embarked on the scheme after hopes of greater religious tolerance under King James I had faded, leaving many English Catholics disappointed.

The thwarting of the Gunpowder Plot was commemorated for many years afterwards by special sermons and other public events such as the ringing of church bells, which evolved into the British variant of Bonfire Night of today.

Their eldest child, the nine-year-old Henry, was considered a handsome and confident boy, and their two younger children, Elizabeth and Charles, were proof that James was able to provide heirs to continue the Protestant monarchy.

He swore that he would not "persecute any that will be quiet and give an outward obedience to the law",[9] and believed that exile was a better solution than capital punishment: "I would be glad to have both their heads and their bodies separated from this whole island and transported beyond seas.

[11] James received an envoy from Albert VII,[7] ruler of the remaining Catholic territories in the Netherlands after over 30 years of war in the Dutch Revolt by English-supported Protestant rebels.

[16] In the absence of any sign that James would move to end the persecution of Catholics, as some had hoped for, several members of the clergy (including two anti-Jesuit priests) decided to take matters into their own hands.

That the Bye Plot had been revealed by Catholics was instrumental in saving them from further persecution, and James was grateful enough to allow pardons for those recusants who sued for them, as well as postponing payment of their fines for a year.

Some Members of Parliament made it clear that, in their view, the "effluxion of people from the Northern parts" was unwelcome, and compared them to "plants which are transported from barren ground into a more fertile one".

To John Gerard, these words were almost certainly responsible for the heightened levels of persecution the members of his faith now suffered, and for the priest Oswald Tesimond, they were a repudiation of the early claims that the King had made, upon which the papists had built their hopes.

[32] The conspirators' principal aim was to kill King James, but many other important targets would also be present at the State Opening of Parliament, including the monarch's nearest relatives and members of the Privy Council.

[41] Also present at the meeting was John Wright, a devout Catholic said to be one of the best swordsmen of his day, and a man who had taken part with Catesby in the Earl of Essex's rebellion three years earlier.

This role gave Percy reason to seek a base in London, and a small property near the Prince's Chamber owned by Henry Ferrers, a tenant of John Whynniard, was chosen.

[51] The building was occupied by Scottish commissioners appointed by the King to consider his plans for the unification of England and Scotland, so the plotters hired Catesby's lodgings in Lambeth, on the opposite bank of the Thames, from where their stored gunpowder and other supplies could be conveniently rowed across each night.

[57] By the time the plotters reconvened at the start of the old style new year on Lady Day, 25 March 1605, three more had been admitted to their ranks; Robert Wintour, John Grant, and Christopher Wright.

[60] In the second week of June, Catesby met in London the principal Jesuit in England, Henry Garnet, and asked him about the morality of entering into an undertaking which might involve the destruction of the innocent, together with the guilty.

Garnet answered that such actions could often be excused, but according to his own account later admonished Catesby during a second meeting in July in Essex, showing him a letter from the pope which forbade rebellion.

Tresham declined both offers (although he did give £100 to Thomas Wintour), and told his interrogators that he had moved his family from Rushton to London in advance of the plot; hardly the actions of a guilty man, he claimed.

Upon reading it, James immediately seized upon the word "blow" and felt that it hinted at "some strategem of fire and powder",[88] perhaps an explosion exceeding in violence the one that killed his father, Lord Darnley, at Kirk o' Field in 1567.

Fawkes visited Keyes, and was given a pocket watch left by Percy, to time the fuse, and an hour later Rookwood received several engraved swords from a local cutler.

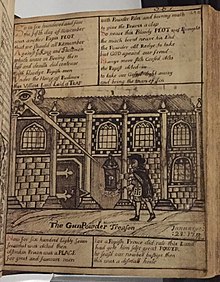

The plot was to have blown up the King at such time as he should have been set on his Royal Throne, accompanied with all his Children, Nobility and Commoners and assisted with all Bishops, Judges and Doctors; at one instant and blast to have ruin'd the whole State and Kingdom of England.

In London, news of the plot was spreading, and the authorities set extra guards on the city gates, closed the ports, and protected the house of the Spanish Ambassador, which was surrounded by an angry mob.

[104] In a letter of 6 November James wrote: "The gentler tortours [tortures] are to be first used unto him, et sic per gradus ad ima tenditur [and thus by steps extended to the bottom depths], and so God speed your good work.

Bates left the group and travelled to Coughton Court to deliver a letter from Catesby, to Garnet and the other priests, informing them of what had transpired, and asking for their help in raising an army.

Although gunpowder does not explode unless physically contained, a spark from the fire landed on the powder and the resultant flames engulfed Catesby, Rookwood, Grant, and a man named Morgan, who was a member of the hunting party.

[111] On 30 January, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, John Grant, and Thomas Bates were tied to hurdles—wooden panels[149]—and dragged through the crowded streets of London to St Paul's Churchyard.

[150] The following day, Thomas Wintour, Ambrose Rookwood, Robert Keyes, and Guy Fawkes were hanged, drawn and quartered, opposite the building they had planned to blow up, in the Old Palace Yard at Westminster.

[161] Poets made a point of describing it as an act so evil that not only was its evil, in John Milton's words, sine nomine in the English language, other neo-Latin poetry described it as (inaudito), unheard of, even among the most wicked nations of history:[162] Neither the Carthaginians infamous in the name of perfidy nor the cruel Scythian nor Turk or the dreaded Sarmatian, nor the Anthropophagi, nurslings of mad savagery, nor any nation as barbarous in the furthermost regions of the world has heard.Milton wrote a poem in 1626 that one commentator has called a "critically vexing poem", In Quintum Novembris.

Reflecting "partisan public sentiment on an English-Protestant national holiday",[163] in the published editions of 1645 and 1673, the poem is preceded by five epigrams on the subject of the Gunpowder Plot, apparently written by Milton in preparation for the larger work.

England might have become a more "Puritan absolute monarchy", as "existed in Sweden, Denmark, Saxony, and Prussia in the seventeenth century", rather than following the path of parliamentary and civil reform that it did.

Subsequent attempts to prove Salisbury's involvement, such as Francis Edwards's 1969 work Guy Fawkes: the real story of the gunpowder plot?, have similarly foundered on the lack of any clear evidence.

1st Earl of Salisbury.

Painting by John de Critz the Elder, 1602.