Gunpowder weapons in the Song dynasty

For example, in 1002 a local militia man named Shi Pu (石普) showed his own versions of fireballs and gunpowder arrows to imperial officials.

[3] A text written by Song Minqiu prior to his death in 1079 includes a gunpowder factory under the Arsenals Administration: Apart from the Offices of the Eight Workshops (Ba Zuo Si), there are also other (government factories), notably the Workshops for General Siege Train Material (Guang Bi Gong Cheng Zuo), and now both of these, Eastern and Western, are under the authority of the Arsenals Administration (Guang Bi Li Jun Qi Jian).

[5]The Chinese flamethrower, known as the Fierce-fire Oil Cabinet, was recorded to have been used in 976 AD when Song naval forces confronted the Southern Tang fleet on the Changjiang.

Southern Tang forces attempted to use flamethrowers against the Song navy, but were accidentally consumed by their own fire when violent winds swept in their direction.

[8] In the early 12th century AD, Kang Yuzhi recorded his memories of military commanders testing out fierce oil fire on a small lakelet.

Allying with the Song, they rose rapidly to the forefront of East Asian powers and defeated the Liao dynasty in a short span of time.

Thirty pieces of thin broken porcelain the size of iron coins are mixed with 3 or 4 lb of gunpowder, and packed around the bamboo tube.

[13] As the Jin account describes, when they attacked the city's Xuanhua Gate, their "fire bombs fell like rain, and their arrows were so numerous as to be uncountable.

[14]The molten metal bomb appeared again in 1129 when Song general Li Yanxian (李彥仙) clashed with Jin forces while defending a strategic pass.

The earliest confirmed employment of the fire lance in warfare was by Song dynasty forces against the Jin in 1132 during the siege of De'an (modern Anlu, Hubei Province).

Pulling their bamboo ropes, they [the porters] ended up drawing the sky bridge back in an anxious and urgent rush, going about fifty paces before stopping.

Song commander Wei Sheng constructed several hundred of these carts known as "at-your-desire-war-carts" (如意戰車), which contained fire lances protruding from protective covering on the sides.

The Song commander "ordered that gunpowder arrows be shot from all sides, and wherever they struck, flames and smoke rose up in swirls, setting fire to several hundred vessels.

(Launched from trebuchets) these thunderclap bombs came dropping down from the air, and upon meeting the water exploded with a noise like thunder, the sulphur bursting into flames.

[23]According to a minor military official by the name of Zhao Wannian (趙萬年), thunderclap bombs were used again to great effect by the Song during the Jin siege of Xiangyang in 1206–1207.

Jin troops were surprised in their encampment while asleep by loud drumming, followed by an onslaught of crossbow bolts, and then thunderclap bombs, which caused a panic of such magnitude that they were unable to even saddle themselves and trampled over each other trying to get away.

The molten metal bomb was used to great effect in 1129 when Song general Li Yanxian (李彥仙) clashed with Jin forces while defending a strategic pass.

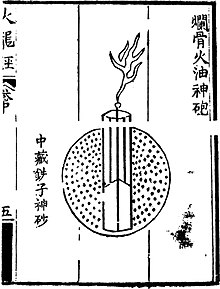

From there it branched off into several different gunpowder weapons known as "eruptors" in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, with different functions such as the "filling-the-sky erupting tube" which spewed out poisonous gas and porcelain shards, the "orifice-penetrating flying sand magic mist tube" (鑽穴飛砂神霧筒) which spewed forth sand and poisonous chemicals into orifices, and the more conventional "phalanx-charging fire gourd" which shot out lead pellets.

According to Jiao Yu in his Huolongjing (mid 14th century), an early Song-era cast-iron cannon known as the 'flying-cloud thunderclap eruptor' (fei yun pi-li pao) was used in the following fashion: The shells are made of cast iron, as large as a bowl and shaped like a ball.

If ten of these shells are fired successfully into the enemy camp, the whole place will be set ablaze…[33]Traditionally the first appearance of the hand cannon is dated to the late 13th century, just after the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty.

[34] However a sculpture depicting a figure carrying a gourd shaped hand cannon was discovered among the Dazu Rock Carvings in 1985 by Robin D. S. Yates.

Not only does the inscription contain the era name and date, it also includes a serial number and manufacturing information which suggests that gun production had already become systematized, or at least become a somewhat standardized affair by the time of its fabrication.

The History of Yuan states that a Jurchen commander known as Li Ting led troops armed with hand cannons into battle against Nayan.

[41] Sinologist Joseph Needham and renaissance siege expert Thomas Arnold provide a more conservative estimate of around 1280 for the appearance of the "true" cannon.

The Mongol war machine moved south and in 1237 attacked the Song city of Anfeng (modern Shouxian, Anhui Province) "using gunpowder bombs [huo pao] to burn the [defensive] towers.

"[47] The Song defenders under commander Du Gao (杜杲) rebuilt the towers and retaliated with their own bombs, which they called the "Elipao," after a famous local pear, probably in reference to the shape of the weapon.

For the first three years the Song defenders had been able to receive supplies and reinforcements by water, but in 1271 the Mongols set up a full blockade with a formidable navy of their own, isolating the two cities.

[15] The next major battle to feature gunpowder weapons was during a campaign led by the Mongol general Bayan, who commanded an army of around two hundred thousand, consisting of mostly Chinese soldiers.

Thus Bayan waited for the wind to change to a northerly course before ordering his artillerists to begin bombarding the city with molten metal bombs, which caused such a fire that "the buildings were burned up and the smoke and flames rose up to heaven.

"[15] This didn't work and the city resisted anyway, so the Mongol army bombarded them with fire bombs before storming the walls, after which followed an immense slaughter claiming the lives of a quarter million.