Gush Katif

[citation needed] Gush Katif began in 1968, when Yigal Allon proposed founding two Nahal settlements in the center of the Gaza Strip.

He viewed the breaking of the continuity between the northern and southern Arab settlements as vital to Israel's security in the area, which had been captured the previous year in the Six-Day War.

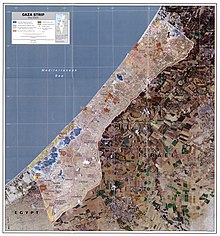

Allon's idea was designed with five key areas (or 'fingers,' being called by some the "five-finger print") slated for Israeli settlements along the Gaza Strip.

The second finger, Netzarim, was connected to Gush Katif until after the Oslo Accords, while the bloc on the dunes north of Gaza, which straddled the Green Line, was more a part of the Ashkelon area communities.

Most of the bloc's communities were established as agricultural cooperatives called moshavs, where the residents from each town would work in clusters of greenhouses just outside the residential areas.

In the bloc's greenhouses, technology was used to grow pest-free leafy vegetables and herbs aiming to meet health, aesthetic and religious requirements.

The money was paid for the greenhouse guts, such as the computerized irrigation systems, as the law in Israel only allowed for the government to pay for the land and structures, as these are not moveable.

[14] Subsequently, the harvest, intended for export via Israel for Europe, was lost due to the Israeli restrictions on the Karni crossing which "was closed more than not", leading to losses in excess of $120,000 per day.

Although the Gush Katif settlements and the roads leading to it were guarded by the Israeli Army's Gaza Division, settlers were still vulnerable to attacks.

During the Second Intifada (2000-2005), Gush Katif was the target of thousands of attacks by Palestinian militants, with over 6000 mortars and Qassam rockets launched into the settlements.

Victims include an 18-year-old killed by a Palestinian sniper in November 2000,[18] and five teenagers who were fatally shot in March 2002 when terrorists infiltrated the Otzem pre-military academy in Atzmona.

Though effectively violating the Disengagement law, which most residents viewed as immoral and illegitimate,[24] most settlers did not voluntarily leave their homes or pack in preparation for eviction.

[26] Originally, the Israeli cabinet had planned to destroy synagogues in the settlement, but the government responded to pressure from religious Jewish organizations and reversed its decision.

[27][28] "Limor Livnat suggested involving UNESCO, with the hopes they would declare Gush Katif synagogues as official World Heritage Sites".

In the context of the Israel–Hamas war of 2023–24, some Israelis have gathered in Yad Mordechai near the Gaza Israel border, in hopes of rebuilding Gush Katif.

[35] In February of 2024, a group of Israeli settlers, some former residents of Gush Katif, gathered at the Beit Hanoun/Erez Crossing with construction materials and weapons with the same goal.