Gustav Holst

The subsequent inspiration of the English folksong revival of the early 20th century, and the example of such rising modern composers as Maurice Ravel, led Holst to develop and refine an individual style.

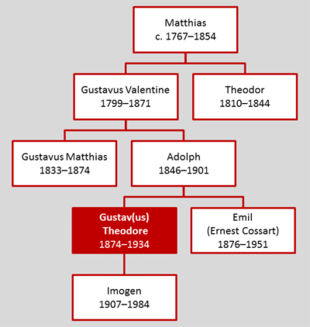

She was of mostly British descent,[n 1] daughter of a respected Cirencester solicitor;[2] the Holst side of the family was of mixed Swedish, Latvian and German ancestry, with at least one professional musician in each of the previous three generations.

[28] His daughter and biographer, Imogen Holst, records that from his fees as a player "he was able to afford the necessities of life: board and lodging, manuscript paper, and tickets for standing room in the gallery at Covent Garden Opera House on Wagner evenings".

[28] Holst respected Stanford, describing him to a fellow-pupil, Herbert Howells, as "the one man who could get any one of us out of a technical mess",[32] but he found that his fellow students, rather than the faculty members, had the greater influence on his development.

Vaughan Williams later observed, "What one really learns from an Academy or College is not so much from one's official teachers as from one's fellow-students ... [we discussed] every subject under the sun from the lowest note of the double bassoon to the philosophy of Jude the Obscure.

[56] According to the composer Edmund Rubbra, who studied under him in the early 1920s, Holst was "a teacher who often came to lessons weighted, not with the learning of Prout and Stainer, but with a miniature score of Petrushka or the then recently published Mass in G minor of Vaughan Williams".

[4] While on tour with the Carl Rosa company Holst had read some of Max Müller's books, which inspired in him a keen interest in Sanskrit texts, particularly the Rig Veda hymns.

[63] Savitri (1908), a chamber opera based on a tale from the Mahabharata; four groups of Hymns from the Rig Veda (1908–14); and two texts originally by Kālidāsa: Two Eastern Pictures (1909–10) and The Cloud Messenger (a setting of the Meghadūta, 1910, premiered in 1913).

[78] At Thaxted, Holst became friendly with the Rev Conrad Noel, known as the "Red Vicar", who supported the Independent Labour Party and espoused many causes unpopular with conservative opinion.

[81] Holst's a cappella carol, "This Have I Done for My True Love", was dedicated to Noel in recognition of his interest in the ancient origins of religion (the composer always referred to the work as "The Dancing Day").

During that festival, Noel, who would become a staunch supporter of Russia's October Revolution, demanded in a Saturday message during the service that there should be a greater political commitment from those who participated in the church activities; his claim that several of Holst's pupils (implicitly those from St Paul's Girls' School) were merely "camp followers" caused offence.

[83] Holst, anxious to protect his students from being embroiled in ecclesiastical conflict, moved the Whitsun Festival to Dulwich, though he himself continued to help with the Thaxted choir and to play the church organ on occasion.

[88] Morley College and St Paul's Girls' School offered him a year's leave of absence, but there remained one obstacle: the YMCA felt that his surname looked too German to be acceptable in such a role.

Arriving via New York he was pleased to be reunited with his brother, Emil, whose acting career under the name of Ernest Cossart had taken him to Broadway; but Holst was dismayed by the continual attentions of press interviewers and photographers.

[118] Holst's absorption of folksong, not only in the melodic sense but in terms of its simplicity and economy of expression,[119] helped to develop a style that many of his contemporaries, even admirers, found austere and cerebral.

She notes that although much of his grand opera, Sita, is "'good old Wagnerian bawling' ... towards the end a change comes over the music, and the beautifully calm phrases of the hidden chorus representing the Voice of the Earth are in Holst's own language.

[134] The chamber opera Savitri (1908) is written for three solo voices, a small hidden female chorus, and an instrumental combination of two flutes, a cor anglais and a double string quartet.

[135] The music critic John Warrack comments on the "extraordinary expressive subtlety" with which Holst deploys the sparse forces: "... [T]he two unaccompanied vocal lines opening the work skilfully convey the relationship between Death, steadily advancing through the forest, and Savitri, her frightened answers fluttering round him, unable to escape his harmonic pull.

Matthews considers the evocation of a North African town in the Beni Mora suite of 1908 the composer's most individual work to that date; the third movement gives a preview of minimalism in its constant repetition of a four-bar theme.

[142] In 1912 Holst composed two psalm settings, in which he experimented with plainsong;[143] the same year saw the enduringly popular St Paul's Suite (a "gay but retrogressive" piece according to Dickinson),[144] and the failure of his large scale orchestral work Phantastes.

[147] In "Mars", a persistent, uneven rhythmic cell consisting of five beats, combined with trumpet calls and harmonic dissonance provides battle music which Short asserts is unique in its expression of violence and sheer terror, "... Holst's intention being to portray the reality of warfare rather than to glorify deeds of heroism".

[152] "Uranus", which follows, has elements of Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique and Dukas's The Sorcerer's Apprentice, in its depiction of the magician who "disappears in a whiff of smoke as the sonic impetus of the movement diminishes from fff to ppp in the space of a few bars".

[158] Head comments on the innovative character of the Hymn: "At a stroke Holst had cast aside the Victorian and Edwardian sentimental oratorio, and created the precursor of the kind of works that John Tavener, for example, was to write in the 1970s".

[160] The influential critic Ernest Newman considered The Perfect Fool "the best of modern British operas",[161] but its unusually short length (about an hour) and parodic, whimsical nature—described by The Times as "a brilliant puzzle"—put it outside the operatic mainstream.

The music, which is largely derived from old English melodies gleaned from Cecil Sharp and other collections, has pace and verve;[4] the contemporary critic Harvey Grace discounted the lack of originality, a facet which he said "can be shown no less convincingly by a composer's handling of material than by its invention".

[4] Richard Greene in Music & Letters describes the piece as "a larghetto dance in a siciliano rhythm with a simple, stepwise, rocking melody", but lacking the power of The Planets and, at times, monotonous to the listener.

Imogen refers to the music as "Holst at his best in a scherzando (playful) frame of mind";[120] Vaughan Williams commented on the lively, folksy rhythms: "Do you think there's a little bit too much 68 in the opera?

A Choral Fantasia of 1930 was written for the Three Choirs Festival at Gloucester; beginning and ending with a soprano soloist, the work, also involving chorus, strings, brass and percussion, includes a substantial organ solo which, says Imogen Holst, "knows something of the 'colossal and mysterious' loneliness of Egdon Heath".

[171] Apart from his final uncompleted symphony, Holst's remaining works were for small forces; the eight Canons of 1932 were dedicated to his pupils, though in Imogen's view that they present a formidable challenge to the most professional of singers.

The limitations of early recording prevented the gradual fade-out of women's voices at the end of "Neptune", and the lower strings had to be replaced by a tuba to obtain an effective bass sound.