Gustav Krist

The Viennese-born and educated Krist worked as a technician in Germany before being mobilised as a twenty-year-old private in the Austro-Hungarian Army on the outbreak of World War I.

[1] Early in the war (November 1914) he was severely wounded and captured by the Russians at the San river[2] defensive line on the Eastern front.

He describes how he was one of only four survivors of a trainload of some three hundred prisoners-of-war who were sent from Koslov to Saratov in December, 1915, after the train-load was singled out for barbaric punishment for stealing wood to keep warm.

For seventy years after him the area was seldom visited by foreign visitors unencumbered by official controls and his accounts show life before the Sovietization of the region.

Following Krasnovodsk, from where inmates were sent to bury 1,200 Turkish prisoners-of-war on an island south of Cheleken who had died of starvation and thirst,[6] Krist was then sent to Fort Alexandovsky, an isolated penal-camp on the Caspian, where troublesome prisoners were concentrated.

After the Bolsheviks freed the prisoners of war, essentially stopping the issue of rations and opening the camp gates, Krist and others were left to fend for themselves and fell into establishing various wheeling-and-dealing industries.

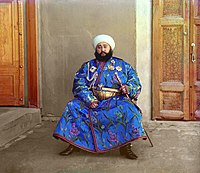

Krist also travelled with Red Cross delegations across Turkistan and in a bizarre episode entered the service of the Emir of Bukhara who was striving to re-establish his full independence in the collapse of the Russian Empire, and helped him set up a mint.

The local soviet in Turkistan promised a train to take the ex-prisoners home in 1920 in return for aid in suppressing mutinous Bolshevik soldiers in Samarkand.

Krist and the remaining prisoners were repatriated late in 1921 through the Baltic States and Germany, having to cross a Russia suffering from famine and the Russian Civil War.

Always a keen observer and with his gift for striking up conversations in Deh i Nau he fell in with a GPU officer who had witnessed the death of Enver Pasha.

[11] Here, with some leisure time, and stimulated by occasional visits of former comrades, he pieced together his war diary as “Pascholl plenny!” (literally 'Get a move on, prisoner').