Gynaeceum

In sorting through the remnants of residential architectural complexes found in sites such as Zagora[4] and Olynthus,[5] archeologists have been able to explore the social dynamics of Ancient Greek society as it developed into the polis or city-state.

Archeologists have developed various perspectives on how architectural design was fundamentally utilized in the domination of women and the lower classes through various periods of history.

Free-born male citizens held political, social and economic power within the domestic and public sphere, as evidenced by the vast amount of historical records available regarding inheritance, property rights, and trade agreements.

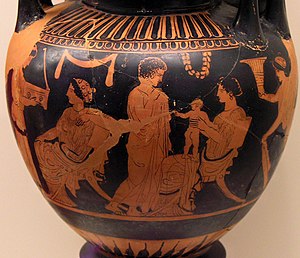

The practice of holding symposium, within the andrōn for the possible purpose of arranging economic agreements within the male aristocratic community, is alluded to in many ceramic vases and murals.

[7] It is in sifting through these surviving remnants of the domestic sphere that archeologists have been able to piece together an understanding of women's social, economic, and political realities.

Artifacts such as ceramic vases, looms, cups, and metal hinges found within the excavated sites suggest social, cultural, and economic clues.

The writings of Xenophon express Socrates' perception of the role of aristocratic women as that of weaving and managing the slaves of the household, while the men having citizenship rights can move freely in the public sphere.

The metal hinges and indentations on structures that could be said to be load bearing suggest the partitioning of space for possible private functions that required limited view by members of the household.

[citation needed] The possible purpose for this gradual change of architectural design is seen by many as that of maintaining the social and hierarchal norms of the oikos and the polis.

Much of the information that is known of women in Ancient Greece comes through literary sources as the written word grew in use during the Classical and Hellenic period, such as Homer's Iliad and the Odyssey and through the writings of Euripides, Xenophon, and Aristotle.

The Laws of Draco (lawgiver) brought forth punishment of women for adultery, and justified the need for guardianship due to the supposed weakness of gender expressed through Aristotle's popular literature.

The home became the domestic private sphere in which women's virtue needed to be protected from the outside world of male dominance and rational thought.

Sarah Pomeroy discusses the role of Homer, Hesiodic poems, and Aristotelian philosophy in painting the picture of women as reproducers of wealth through the maintenance of the home and slaves.