White-rumped vulture

[1] In the 1980s, the global population was estimated at several million individuals, and it was thought to be "the most abundant large bird of prey in the world".

[3] The white-rumped vulture was formally described in 1788 by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in his revised and expanded edition of Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae.

[4] Gmelin based his description on the "Bengal vulture" that had been described and illustrated in 1781 by the English ornithologist John Latham in his multi-volume A General Synopsis of Birds.

[5][6] The white-rumped vulture is now one of eight species placed in the genus Gyps that was introduced in 1809 by the French zoologist Marie Jules César Savigny.

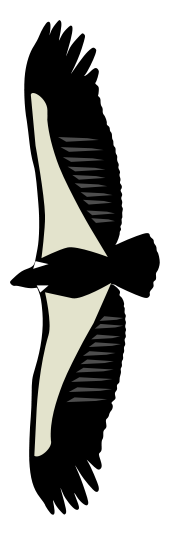

In flight, the adults show a dark leading edge of the wing and has a white wing-lining on the underside.

[11][12] This vulture builds its nest on tall trees often near human habitations in northern and central India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and southeast Asia, laying one egg.

A 19th century experimenter who hid a carcass of dog in a sack in a tree considered it capable of finding carrion by smell.

[14][15] White-rumped vultures usually become active when the morning sun is warming up the air so that thermals are sufficient to support their soaring.

[11] In Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, white-rumped vultures used foremost Terminalia arjuna and Spondias mangifera trees for nesting at a mean height of 26.73 m (87.7 ft).

[28][29] Ticks, Argas (Persicargas) abdussalami, have been collected in numbers from the roost trees of these vultures in Pakistan.

[31] The white-rumped vulture was originally very common especially in the Gangetic plains of India, and often seen nesting on the avenue trees within large cities in the region.

Hugh Whistler noted for instance in his guide to the birds of India that it “is the commonest of all the vultures of India, and must be familiar to those who have visited the Towers of Silence in Bombay.”[32] T. C. Jerdon noted that “[T]his is the most common vulture of India, and is found in immense numbers all over the country, ... At Calcutta one may frequently be seen seated on the bloated corpse of some Hindoo floating up or down with the tide, its wing spread, to assist in steadying it...”[33] Before the 1990s they were even seen as a nuisance, particularly to aircraft as they were often involved in bird strikes.

[34][35] In 1941 Charles McCann wrote about the death of Borassus palms due to the effect of excreta from vultures roosting on them.

The decline has been widely attributed to poisoning by diclofenac, which is used as veterinary non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), leaving traces in cattle carcasses which when fed on leads to kidney failure in birds.

[45] An alternate hypothesis is an epidemic of avian malaria, as implicated in the extinctions of birds in the Hawaiian islands.

[49] In Southeast Asia, the near-total disappearance of white-rumped vultures predated the present diclofenac crisis, and probably resulted from the collapse of large wild ungulate populations and improved management of dead livestock, resulting in a lack of available carcasses for vultures.

[51] Campaigns to ban the use of diclofenac in veterinary practice have been underway in several South Asian countries.

[52] Conservation measures have included reintroduction, captive-breeding programs and artificial feeding or "vulture restaurants".

However, they died after a few weeks, apparently because their parents were an inexperienced couple breeding for the first time in their lives – a fairly common occurrence in birds of prey.