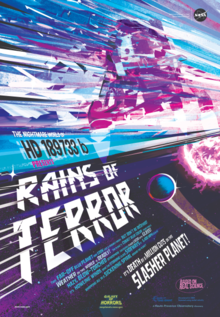

HD 189733 b

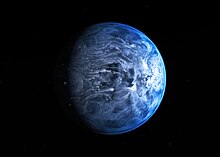

HD 189733 b was also the first exoplanet to have its thermal map constructed,[9][10] possibly to be detected through polarimetry,[11] its overall color determined (deep blue),[11][3] its transit viewed in the X-ray spectrum, and to have carbon dioxide confirmed as being present in its atmosphere.

The measurements in polarized light have since been disputed by two separate teams using more sensitive polarimeters,[16][17][18] with upper limits of the polarimetric signal provided therein.

In mid January 2008, spectral observation during the planet's transit using that model found that if molecular hydrogen exists, it would have an atmospheric pressure of 410 ± 30 mbar of 0.1564 solar radii.

In the visible region of the spectrum, thanks to their high absorption cross sections, atomic sodium and potassium can be investigated.

Like most hot Jupiters, this planet is thought to be tidally locked to its parent star, meaning it has a permanent day and night.

A temperature range of 973 ± 33 K to 1,212 ± 11 K was discovered, indicating that the absorbed energy from the parent star is distributed fairly evenly through the planet's atmosphere.

The region of peak temperature was offset 30 degrees east of the substellar point, as predicted by theoretical models of hot Jupiters taking into account a parameterized day to night redistribution mechanism.

[35] On July 11, 2007, a team led by Giovanna Tinetti published the results of their observations using the Spitzer Space Telescope concluding there is solid evidence for significant amounts of water vapor in the planet's atmosphere.

[36] Follow-up observations made using the Hubble Space Telescope confirm the presence of water vapor, neutral oxygen and also the organic compound methane.

[37][40] Nonetheless, the presence of roughly 0.004% of water vapour fraction by volume in atmosphere of HD 189733 b was confirmed with high-resolution emission spectra taken in 2021.

[41] While transiting the system also clearly exhibits the Rossiter–McLaughlin effect, shifting in photospheric spectral lines caused by the planet occulting a part of the rotating stellar surface.

Theoretical research since 2000 suggested that an exoplanet very near to the star that it orbits may cause increased flaring due to the interaction of their magnetic fields, or because of tidal forces.

In 2019, astronomers analyzed data from Arecibo Observatory, MOST, and the Automated Photoelectric Telescope, in addition to historical observations of the star at radio, optical, ultraviolet, and X-ray wavelengths to examine these claims.

They found that the previous claims were exaggerated and the host star failed to display many of the brightness and spectral characteristics associated with stellar flaring and solar active regions, including sunspots.

"[46] Some researchers had also suggested that HD 189733 accretes, or pulls, gas from its orbiting exoplanet at a rate similar to those found around young protostars in T Tauri Star systems.

[48] Two studies by the same team in 2019 and 2020 proposed exo-Io candidates around a number of hot Jupiters, including HD 189733 b and WASP-49b, based on detected sodium[49] and potassium,[50] consistent with evaporating exomoons and/or their corresponding gas torus.

From top left to lower right: WASP-12b , WASP-6b , WASP-31b , WASP-39b , HD 189733 b , HAT-P-12b , WASP-17b , WASP-19b , HAT-P-1b and HD 209458 b .