Habitability of red dwarf systems

Current arguments concerning the habitability of red dwarf systems are unresolved, and the area remains an open question of study in the fields of climate modeling and the evolution of life on Earth.

[3] A major impediment to the development of life in red dwarf systems is the intense tidal heating caused by the eccentric orbits of planets around their host stars.

[4][5] Other tidal effects reduce the probability of life around red dwarfs, such as the lack of planetary axial tilts and the extreme temperature differences created by one side of planet permanently facing the star and the other perpetually turned away.

[7] Non-tidal factors further reduce the prospects for life in red-dwarf systems, such as spectral energy distributions shifted toward the infrared side of the spectrum relative to the Sun and small circumstellar habitable zones due to low light output.

The brightest red dwarf in Earth's night sky, Lacaille 8760 (+6.7) is visible to the naked eye only under ideal viewing conditions.

Red dwarfs, by contrast, could live for trillions of years, as their nuclear reactions are far slower than those of larger stars,[a] meaning that life would have longer to evolve and survive.

[22][23] Photosynthesis on such a planet would be difficult, as much of the low luminosity falls under the lower energy infrared and red part of the electromagnetic spectrum, and would therefore require additional photons to achieve excitation potentials.

[24] However, further research, including a consideration of the amount of photosynthetically active radiation, has suggested that tidally locked planets in red dwarf systems might at least be habitable for higher plants.

[26] However, a similar effect of preferential absorption by water ice would increase its temperature relative to an equivalent amount of radiation from a Sun-like star, thereby extending the habitable zone of red dwarfs outward.

Thus, terrestrial planets in the actual habitable zones, if provided with abundant surface water in their formation, would have been subject to a runaway greenhouse effect for several hundred million years.

[32] Plant life would have to adapt to the constant gale, for example by anchoring securely into the soil and sprouting long flexible leaves that do not snap.

[34] Subsequent research has shown that seawater, too, could effectively circulate without freezing solid if the ocean basins were deep enough to allow free flow beneath the night side's ice cap.

In contrast to the predictions of earlier studies on tidal Venuses, though, this "trapped water" may help to stave off runaway greenhouse effects and improve the habitability of red dwarf systems.

[8] This caveat has proven difficult, however, since flares produce torrents of charged particles that could strip off sizable portions of the planet's atmosphere.

[41] Scientists who believe in the Rare Earth hypothesis doubt that red dwarfs could support life amid strong flaring.

Active red dwarfs that emit coronal mass ejections (CMEs) would bow back the magnetosphere until it contacted the planetary atmosphere.

[42][43][44] However, it was found that red dwarfs have a much lower CME rate than expected from their rotation or flare activity, and large CMEs occur rarely.

Another way that life could initially protect itself from radiation would be remaining underwater until the star had passed through its early flare stage, assuming the planet could retain enough of an atmosphere to sustain liquid oceans.

[24] For a planet around a red dwarf star to support life, it would require a rapidly rotating magnetic field to protect it from the flares.

If a planet forms far away from a red dwarf so as to avoid atmospheric erosion, and then migrates into the star's habitable zone after this turbulent initial period, it is possible for life to develop.

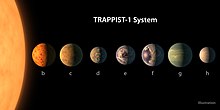

A study of archival Spitzer data gives the first idea and estimate of how frequent Earth-sized worlds are around ultra-cool dwarf stars: 30–45%.