Haitian Vodou

Its structure arose from the blending of the traditional religions of those enslaved West and Central Africans brought to the island of Hispaniola, among them Kongo, Fon, and Yoruba.

[93] Vodouists often refer to the lwa living in the sea or in rivers,[86] or alternatively in Ginen,[87] a term encompassing a generalized understanding of Africa as the ancestral land of the Haitian people.

[133] The Gede's symbol is an erect penis,[140] while the banda dance associated with them involves sexual-style thrusting,[141] and those possessed by these lwa typically make sexual innuendos.

[149] Scholars like Desmangles have argued that Vodouists originally adopted the Roman Catholic saints to conceal lwa worship when the latter was illegal during the colonial period.

[150] Observing Vodou in the latter part of the 20th century, Donald J. Cosentino argued that by that point, the use of Roman Catholic saints reflected the genuine devotional expression of many Vodouists.

[151] The scholar Marc A. Christophe concurred, stating that most modern Vodouists genuinely see the saints and lwa as one, reflecting Vodou's "all-inclusive and harmonizing characteristics".

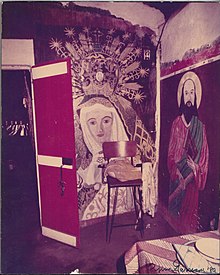

[152] Many Vodouists possess chromolithographic prints of the saints,[151] while images of these Christian figures can also be found on temple walls,[153] and on the drapo flags used in Vodou ritual.

[173] Vodou also teaches that the dead continue to participate in human affairs,[174] with these spirits often complaining that they suffer from hunger, cold, and damp,[175] and thus requiring sacrifices from the living.

[178] This view of destiny has been interpreted as encouraging a fatalistic outlook,[179] something that the religion's critics, especially from Christian backgrounds, have argued has discouraged Vodouists from improving their society.

[180] This has been extended into an argument that Vodou is responsible for Haiti's poverty,[181] a view that in turn has been accused of being rooted in European colonial prejudices towards Africans.

[193] Although there are accounts of male Vodou priests mistreating their female followers,[194] in the religion women can also lay claim to moral authority as social and spiritual leaders.

[260] The area around the ounfò often contains objects dedicated to particular lwa, such as a pool of water for Danbala, a black cross for Baron Samedi, and a pince (iron bar) embedded in a brazier for Criminel.

[270] Congregants often form a sosyete soutyen (société soutien, support society), through which subscriptions are paid to help maintain the ounfò and organize the major religious feasts.

[271] Another ritual figure sometimes present is the prèt savann ("bush priest"), a man with a knowledge of Latin who is capable of administering Catholic baptisms, weddings, and the last rites, and who is willing to perform these at Vodou ceremonies.

[297] Since developing in the mid-19th century, chromolithography has also had an impact on Vodou imagery, facilitating the widespread availability of images of the Roman Catholic saints who are equated with the lwa.

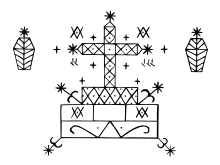

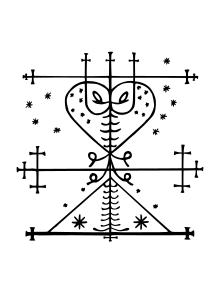

[310] Often made of silk or velvet and decorated with shiny objects such as sequins,[311] the drapo often feature either the vèvè of specific lwa they are dedicated to or depictions of the associated Roman Catholic saint.

[177] A manje sèk (dry meal) is an offering of grains, fruit, and vegetables that often precedes a simple ceremony; it takes its name from the absence of blood.

[387] Other forms of divination used by Vodouists include the casting of shells,[387] cartomancy,[388] studying leaves, coffee grounds or cinders in a glass, or looking into a candle flame.

[392] To heal, Vodou specialists often prescribe baths, consisting of water infused with various ingredients,[393] or produce powders for a specific purpose, such as to attract good luck or aid seduction.

[406] It holds that humans can cause supernatural harm to others, either unintentionally or deliberately,[407] in the latter case exerting power over a person through possession of hair or nail clippings belonging to them.

[415] According to Haitian popular belief, bòkò engage in anvwamò ("expeditions"), setting the dead against an individual to cause the latter's sudden illness and death,[416] and utilise baka, malevolent spirits sometimes in animal form.

[426] The night after the funeral, the novena takes place at the home of the deceased, involving Roman Catholic prayers;[427] a mass for them is held a year after death,[428] sometimes performed by a prèt savann.

[446] The reality of this phenomenon is contested,[444] although the anthropologist Wade Davis argued that this was based on a real practice whereby Bizango societies used poisons to make certain individuals more pliant.

[464] Another popular pilgrimage site, again typically visited in July, is Saut d'Eau ("waterfall") or Sodo, located outside the village of Ville-Bonheur where the Virgin Mary (Èzili) allegedly appeared in the 1840s.

[150] Afro-Haitians adopted other aspects of French colonial culture;[486] Vodou drew influence from European grimoires,[487] commedia performances,[488] and Freemasonry, with Masonic lodges having been established across Saint-Domingue in the 18th century.

[489] Vodou rituals took place in secret, usually at night; one such rite was described during the 1790s by a white man, Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry.

[492] According to legend, a Vodou ritual took place in Bois-Caïman on 14 August 1791 at which the participants swore to overthrow the slave owners before massacring local whites and sparking the Revolution.

[513] American occupation encouraged international interest in Vodou,[514] something catered for in the sensationalist writings of Faustin Wirkus, William Seabrook, and John Craige,[515] as well as in Vodou-themed shows for tourists.

[552] Throughout Haitian history, Christians have often presented Vodou as Satanic,[553] while in broader Anglophone and Francophone society it has been widely associated with sorcery, witchcraft, and black magic.

[564] Documentaries focusing on Vodou have appeared[565]—such as Maya Deren's 1985 film Divine Horsemen[566][567] or Anne Lescot and Laurence Magloire's 2002 work Of Men and Gods[568]—which have in turn encouraged some viewers to take a practical interest in the religion.