Halakha

Halakha (/hɑːˈlɔːxə/ hah-LAW-khə;[1] Hebrew: הֲלָכָה, romanized: hălāḵā, Sephardic: [halaˈχa]), also transliterated as halacha, halakhah, and halocho (Ashkenazic: [haˈlɔχɔ]), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Written and Oral Torah.

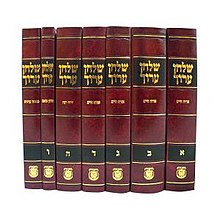

Halakha is based on biblical commandments (mitzvot), subsequent Talmudic and rabbinic laws, and the customs and traditions which were compiled in the many books such as the Shulchan Aruch.

[7] Halakha is often contrasted with aggadah ("the telling"), the diverse corpus of rabbinic exegetical, narrative, philosophical, mystical, and other "non-legal" texts.

With few exceptions, controversies are not settled through authoritative structures because during the Jewish diaspora, Jews lacked a single judicial hierarchy or appellate review process for halakha.

[11] Currently, many of the 613 commandments cannot be performed until the building of the Temple in Jerusalem and the universal resettlement of the Jewish people in the Land of Israel by the Messiah.

Historian Yitzhak Baer argued that there was little pure academic legal activity at this period and that many of the laws originating at this time were produced by a means of neighbourly good conduct rules in a similar way as carried out by Greeks in the age of Solon.

In branches of Judaism that follow halakha, lay individuals make numerous ad-hoc decisions but are regarded as not having authority to decide certain issues definitively.

As a result, halakha has developed in a somewhat different fashion from Anglo-American legal systems with a Supreme Court able to provide universally accepted precedents.

Depending on the stature of the posek and the quality of the decision, an interpretation may also be gradually accepted by other rabbis and members of other Jewish communities.

These examples of takkanot which may be executed out of caution lest some might otherwise carry the mentioned items between home and the synagogue, thus inadvertently violating a Sabbath melakha.

The antiquity of the rules can be determined only by the dates of the authorities who quote them; in general, they cannot safely be declared older than the tanna ("repeater") to whom they are first ascribed.

The Talmud gives no information concerning the origin of the middot, although the Geonim ("Sages") regarded them as Sinaitic (Law given to Moses at Sinai).

According to Akiva, the divine language of the Torah is distinguished from the speech of men by the fact that in the former no word or sound is superfluous.

For example, Saul Lieberman argues that the names of rabbi Ishmael's middot (e. g., kal vahomer, a combination of the archaic form of the word for "straw" and the word for "clay" – "straw and clay", referring to the obvious [means of making a mud brick]) are Hebrew translations of Greek terms, although the methods of those middot are not Greek in origin.

The rabbis, who made many additions and interpretations of Jewish Law, did so only in accordance with regulations they believe were given for this purpose to Moses on Mount Sinai, see Deuteronomy 17:11.

[22] Conservative Judaism holds that halakha is normative and binding, and is developed as a partnership between people and God based on Sinaitic Torah.

While there are a wide variety of Conservative views, a common belief is that halakha is, and has always been, an evolving process subject to interpretation by rabbis in every time period.

Reconstructionist Judaism holds that halakha is normative and binding, while also believing that it is an evolving concept and that the traditional halakhic system is incapable of producing a code of conduct that is meaningful for, and acceptable to, the vast majority of contemporary Jews.

Although Orthodox Judaism acknowledges that rabbis have made many decisions and decrees regarding Jewish Law where the written Torah itself is nonspecific, they did so only in accordance with regulations received by Moses on Mount Sinai (see Deuteronomy 5:8–13).

[31] For instance, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik believes that the job of a halakhic decisor is to apply halakha − which exists in an ideal realm−to people's lived experiences.

[34] A key practical difference between Conservative and Orthodox approaches is that Conservative Judaism holds that its rabbinical body's powers are not limited to reconsidering later precedents based on earlier sources, but the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards (CJLS) is empowered to override Biblical and Taanitic prohibitions by takkanah (decree) when perceived to be inconsistent with modern requirements or views of ethics.

The CJLS has used this power on a number of occasions, most famously in the "driving teshuva", which says that if someone is unable to walk to any synagogue on the Sabbath, and their commitment to observance is so loose that not attending synagogue may lead them to drop it altogether, their rabbi may give them a dispensation to drive there and back; and more recently in its decision prohibiting the taking of evidence on mamzer status on the grounds that implementing such a status is immoral.

The CJLS has also held that the Talmudic concept of Kavod HaBriyot permits lifting rabbinic decrees (as distinct from carving narrow exceptions) on grounds of human dignity, and used this principle in a December 2006 opinion lifting all rabbinic prohibitions on homosexual conduct (the opinion held that only male-male anal sex was forbidden by the Bible and that this remained prohibited).

[37] The Conservative approach to halakhic interpretation can be seen in the CJLS's acceptance of Rabbi Elie Kaplan Spitz's responsum decreeing the biblical category of mamzer as "inoperative.

"[38] The CJLS adopted the responsum's view that the "morality which we learn through the larger, unfolding narrative of our tradition" informs the application of Mosaic law.

[38] The responsum cited several examples of how the rabbinic sages declined to enforce punishments explicitly mandated by Torah law.

The examples include the trial of the accused adulteress (sotah), the "law of breaking the neck of the heifer," and the application of the death penalty for the "rebellious child.

"[39] Kaplan Spitz argues that the punishment of the mamzer has been effectively inoperative for nearly two thousand years due to deliberate rabbinic inaction.

Further he suggested that the rabbis have long regarded the punishment declared by the Torah as immoral, and came to the conclusion that no court should agree to hear testimony on mamzerut.