Halifax Explosion

On Mont-Blanc, the impact damaged benzol barrels stored on deck, causing them to leak vapours which were ignited by sparks from the collision, setting off a fire on board that quickly grew out of control.

[3] A pressure wave snapped trees, bent iron rails, demolished buildings, grounded vessels (including Imo, which was washed ashore by the ensuing tsunami), and scattered fragments of Mont-Blanc for kilometres.

[6][7] The completion of the Intercolonial Railway and its Deep Water Terminal in 1880 allowed for increased steamship trade and led to accelerated development of the port area,[8] but Halifax faced an economic downturn in the 1890s as local factories struggled to compete with businesses in central Canada.

[15] In 1915, management of the harbour fell under the control of the Royal Canadian Navy; by 1917 there was a growing naval fleet in Halifax, including patrol ships, tugboats, and minesweepers.

[19] The success of German U-boat attacks on ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean led the Allies to institute a convoy system to reduce losses while transporting goods and soldiers to Europe.

These factors drove a major military, industrial, and residential expansion of the city,[11] and the weight of goods passing through the harbour increased nearly ninefold.

[28] She intended to join a slow convoy gathering in Bedford Basin readying to depart for Europe but was too late to enter the harbour before the nets were raised.

[25] Ships carrying dangerous cargo were not allowed into the harbour before the war, but the risks posed by German submarines had resulted in a relaxation of regulations.

[31] Imo was granted clearance to leave Bedford Basin by signals from the guard ship HMCS Acadia at approximately 7:30 on the morning of 6 December,[32] with Pilot William Hayes on board.

[34] Soon afterwards, Imo was forced to head even further towards the Dartmouth shore after passing the tugboat Stella Maris, which was travelling up the harbour to Bedford Basin near mid-channel.

Horatio Brannen, the captain of Stella Maris, saw Imo approaching at excessive speed and ordered his ship closer to the western shore to avoid an accident.

Unable to ground his ship for fear of a shock that would set off his explosive cargo, Mackey ordered Mont-Blanc to steer hard to port (starboard helm) and crossed the bow of Imo in a last-second bid to avoid a collision.

Captain Brannen and Albert Mattison of Niobe agreed to secure a line to the French ship's stern so as to pull it away from the pier to avoid setting it on fire.

A tsunami was formed by water surging in to fill the void;[60] it rose as high as 18 metres (60 ft) above the high-water mark on the Halifax side of the harbour.

[65] Overturned stoves and lamps started fires throughout Halifax,[66] particularly in the North End, where entire city blocks burned, trapping residents inside their houses.

Firefighter Billy Wells, who was thrown away from the explosion and had his clothes torn from his body, described the devastation survivors faced: "The sight was awful, with people hanging out of windows dead.

[70] The death toll could have been worse had it not been for the self-sacrifice of an Intercolonial Railway dispatcher, Patrick Vincent (Vince) Coleman, operating at the railyard about 230 metres (750 ft) from Pier 6, where the explosion occurred.

10, the overnight train from Saint John, is believed to have heeded the warning and stopped a safe distance from the blast at Rockingham, saving the lives of about 300 railway passengers.

The initial informal response was soon joined by surviving policemen, firefighters and military personnel who began to arrive, as did anyone with a working vehicle; cars, trucks and delivery wagons of all kinds were enlisted to collect the wounded.

[84] Troops at gun batteries and barracks immediately turned out in case the city was under attack, but within an hour switched from defence to rescue roles as the cause and location of the explosion were determined.

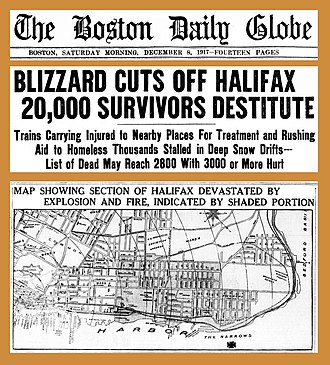

Trains en route from other parts of Canada and from the United States were stalled in snowdrifts, and telegraph lines that had been hastily repaired following the explosion were again knocked down.

Thousands of people had stopped to watch the ship burning in the harbour, many from inside buildings, leaving them directly in the path of glass fragments from shattered windows.

[117] The Black community of Africville, on the southern shores of Bedford Basin adjacent to the Halifax Peninsula, was spared the direct force of the blast by the shadow effect of the raised ground to the south.

[126] While John Johansen, the Norwegian helmsman of Imo, was being treated for serious injuries sustained during the explosion, it was reported to the military police that he had been behaving suspiciously.

[131] The inquiry's report of 4 February 1918 blamed Mont-Blanc's captain, Aimé Le Médec, the ship's pilot, Francis Mackey, and Commander F. Evan Wyatt, the Royal Canadian Navy's chief examining officer in charge of the harbour, gates and anti-submarine defences, for causing the collision.

[131] Subsequent appeals to the Supreme Court of Canada (19 May 1919), and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London (22 March 1920), determined Mont-Blanc and Imo were equally to blame for navigational errors that led to the collision.

English town planner Thomas Adams and Montreal architectural firm Ross and Macdonald were recruited to design a new housing plan for Richmond.

Adams, inspired by the Victorian garden city movement, aimed to provide public access to green spaces and to create a low-rise, low-density, and multifunctional urban neighbourhood.

[124] Every building in the Halifax dockyard required some degree of rebuilding, as did HMCS Niobe and the docks themselves; all of the Royal Canadian Navy's minesweepers and patrol boats were undamaged.

[161] Hugh MacLennan's novel Barometer Rising (1941) is set in Halifax at the time of the explosion and includes a carefully researched description of its impact on the city.