Haliotis cracherodii

This used to be the most abundant large marine mollusk on the west coast of North America[citation needed], but now, because of overfishing and the withering syndrome, it has much declined in population and the IUCN Red List has classed the black abalone as Critically Endangered.

The exterior of the shell is smoother than most abalone, or may have low obsolete coarse spiral lirae and lines of growth.

[8] Prehistoric distribution has been confirmed along much of this range from archaeological recovery at a variety of Pacific coastal Native American sites.

For example, Chumash peoples in central California were known to have been harvesting black abalone approximately a millennium earlier in the Morro Bay area.

[7] Juveniles tend to reside in crevices to reduce their risk of predation, but the larger adults will move out onto rock surfaces.

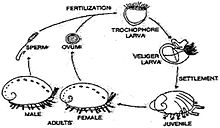

[11] Black abalone are broadcast spawners, and successful spawning requires that individuals be grouped closely together.

[10] Juveniles do not tend to disperse great distances, and current populations of black abalone are generally composed of individuals that were spawned locally.

[7] Predators of this species other than mankind are sea otters (such as the southern sea otter, Enhydra lutris), fish (such as the California sheephead, Semicossyphus pulcher) and invertebrates, including crustaceans such as the striped shore crab, Pachygrapsus crassipes, and spiny lobsters.

After the Chumash and other California Indians were devastated by European diseases, and sea otters were nearly eradicated from California waters by the historic fur trade, black abalone populations rebounded and attracted an intensive intertidal fishery conducted primarily by Chinese immigrants from the 1850s to about 1900.

[10] On June 23, 1999, the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) designated the black abalone as a candidate for protection under the Endangered Species Act (64 FR 33466).

Other threats include coastal development for residential areas, harbours and waste discharges, compounded by commercial and recreational fishing of the black abalone.

In many locations, percentages greater than 90% of individuals have been lost, and in some places, a total loss of the black abalone population occurred.

[7][20][21] This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "Haliotis cracherodii" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.