Hall house

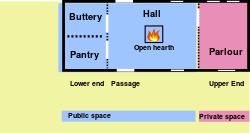

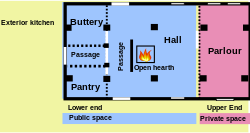

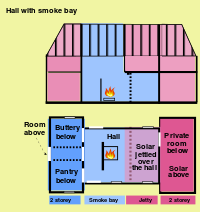

In Old English, a "hall" is simply a large room enclosed by a roof and walls, and in Anglo-Saxon England simple one-room buildings, with a single hearth in the middle of the floor for cooking and warmth, were the usual residence of a lord of the manor and his retainers.

The public area is the place for living: cooking, eating, meeting and playing, while private space is for withdrawing and for storing valuables.

[2] By about 1400, in lowland Britain, with changes in settlement patterns and agriculture, people were thinking of houses as permanent structures rather than temporary shelter.

The hall house, having started in the Middle Ages as a home for a lord and his community of retainers, permeated to the less well-off during the early modern period.

During the sixteenth century, the rich crossed what Brunskill describes as the "polite threshold" and became more likely to employ professionals to design their homes.

A successful building was likely to be extended to follow the fashion or to add needed additional accommodation, and it is even possible for a medieval hall house to be hidden within an apparently much later building and to go unrecognized for what it is, until alteration or demolition reveals the tell-tale smoke-blackened roof timbers of the original open hall.

Stone, flint, cobble, brick and earth when available could be used to build walls that would support the mass on the roof structure.

A thirteenth century example of a stone roofed hall-house survives in a good state of preservation at Aydon Hall in Northumberland.

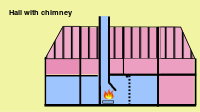

Placing the hearth at the lower end of the hall was deliberate because combustion could be controlled by varying the through draught between the two doors.

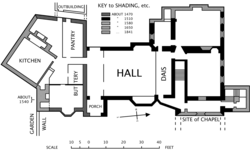

Fireplaces and chimney stacks could be fitted into existing buildings against the passage, or against the side walls or even at the upper end of the hall.

[13] In the earliest houses combustion of wood was helped by increasing the airflow by placing the logs on iron firedogs.

[16] [17] In larger houses, fireplaces and chimneys were first used as supplementary heating in the parlour, before eventually suppressing the open hearth.

The design of the coal grate was important and the open fire became more sophisticated and enclosed leading in later centuries to the coal burning kitchen range with its hob, oven and water boiler, and the Triplex type kitchen range with a back boiler and the 1922 AGA cooker.

A large number of former hall-houses do still exist and many are cared for by the National Trust, English Heritage, local authorities and private owners.

Wealden hall houses can be found in the weald of Kent and Sussex where the combination of good quality hard wood and wealthy yeoman farmers and iron founders prevailed in the 14th to 16th centuries.

The Weald and Downland Open Air Museum has a collection of rescued house which have been extensively researched prior to their reconstruction.

Hole Cottage in Kent near Cowden (operated by Landmark Trust) has an intact private dwelling wing of a Wealden hall house.

English Heritage has listed the building at Grade II* for its architectural and historical importance, and it has been described "the finest timber-framed house between London and Brighton".

[20][21] Crawley's development as a permanent settlement dates from the early 13th century, when a charter was granted for a market to be held;[22] a church was founded by 1267.

Some sources assert that a building stood on the site of the Ancient Priors by this time, claiming that it was built between 1150[24] and 1250[25] and was used as a chantry-house.

[29] In the early 18th century, the prominent local ironmaster Leonard Gale—holder of much property in the Crawley area—owned the building, and is believed to have lived there.

Only the great hall, built around 1530 for Sir Robert Hesketh, survives from the original building but it indicates the wealth and position of the family.

In 1936 Rufford Old Hall, with its collection of arms and armour and 17th century oak furniture, was donated to the National Trust by Thomas Fermor-Hesketh, 1st Baron Hesketh.

[34] In 1661 a Jacobean style rustic brick wing was built at right angles to the great hall which contrasts with the medieval black and white timbering.

This wing was built from small two-inch bricks similar to Bank Hall, and Carr House and St Michael's Church in Much Hoole.

[37] Ufford Hall is a Grade II* listed manor house in Fressingfield, Suffolk, England, dating back to the thirteenth century.

At least twenty raised-aisled houses have been identified in the area, "forming a characteristic group, rarely found elsewhere in England".

[39] The Hall has attracted the attention of architectural historians, such as Pevsner[40] and Sandon,[38] and has been described as the “ultimate development (…) of the early hall house.”[41] Its most noteworthy features include: cross-beamed ceiling in the parlour which has not been disturbed since the late fifteenth century or early sixteenth century; striking original sixteenth-century mullioned and transomed windows; back-to-back stuccoed fireplaces on both floors and chimney stacks of Tudor origin; fine Jacobean dog-leg staircase with turned balusters and newel posts with ball finials.

[46] In the 16th century the hall was divided horizontally by the addition of an inserted floor supported by moulded cross beams.

[49] Whitestaunton Manor in south Somerset was built in the 15th century as a hall house and has been designated as a Grade I listed building.