Halloween (1978 film)

On the night of Halloween, 1963, in the suburban Illinois town of Haddonfield, six-year-old Michael Myers brutally stabs his teenage sister Judith to death with a chef's knife.

"[14] In another interview, Carpenter said that readings of the film as a morality play "completely missed the point," adding, "The one girl who is the most sexually uptight just keeps stabbing this guy with a long knife.

"[17] Critics such as John Kenneth Muir state that female characters such as Laurie Strode survive not because of "any good planning" or their own resourcefulness, but sheer luck.

Loomis states, "I spent eight years trying to reach him [Michael Myers], and then another seven trying to keep him locked up because I realized that what was living behind that boy's eyes was purely and simply ...

"[28] Carpenter's first-person point-of-view compositions were employed with steadicam; Telotte argues, "As a result of this shift in perspective from a disembodied, narrative camera to an actual character's eye ... we are forced into a deeper sense of participation in the ensuing action.

According to scholar Nicholas Rogers, Carpenter's "frequent use of the unmounted first-person camera to represent the killer's point of view ... invited [viewers] to adopt the murderer's assaultive gaze and to hear his heavy breathing and plodding footsteps as he stalked his prey.

"[26] Film analysts have noted its delayed or withheld representations of violence, characterized as the "false startle" or "the old tap-on-the-shoulder routine" in which the stalkers, murderers, or monsters "lunge into our field of vision or creep up on a person.

"[31] Critic Susan Stark described the film's opening sequence in her 1978 review: In a single, wonderfully fluid tracking shot, the camera establishes the quiet character of a suburban street, the sexual hanky-panky going on between a teenage couple in one of the staid-looking homes, the departure of the boyfriend, a hand in the kitchen drawer removing a butcher's knife, the view on the way upstairs from behind the eye-slits of a Halloween mask, the murder of a half-nude young girl seated at her dressing table, the descent downstairs and whammo!

The killer stands speechless on the lawn, holding the bloody knife, a small boy in a satin clown suit with a newly-returned parent on each side shrieking in an attempt to find out what the spectacle means.

Hill, who had worked as a babysitter during her teenage years, wrote most of the female characters' dialogue,[46] while Carpenter drafted Loomis' speeches on the soullessness of Michael Myers.

I decided to make a film I would love to have seen as a kid, full of cheap tricks like a haunted house at a fair where you walk down the corridor and things jump out at you.

[64] Kyes had previously starred in Assault on Precinct 13 (as had Cyphers) and happened to be dating Halloween's art director Tommy Lee Wallace when filming began.

[65] Carpenter chose P. J. Soles to play Lynda Van Der Klok, another loquacious friend of Laurie's, best remembered in the film for dialogue peppered with the word "totally.

"[66] Soles was an actress known for her supporting role in Carrie (1976) and her minor part in The Boy in the Plastic Bubble (1976) and would subsequently play Riff Randall in the 1979 film Rock 'n Roll High School.

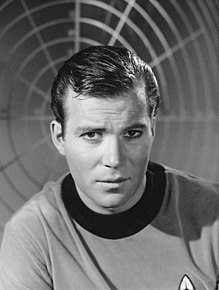

[69] The role of "The Shape"—as the masked Michael Myers character was billed in the end credits—was played by Nick Castle, who befriended Carpenter while they attended the University of Southern California.

[75][33] Akkad worried over the tight, four-week schedule, low budget, and Carpenter's limited experience as a filmmaker, but told Fangoria: "Two things made me decide.

[82] The vehicle stolen by Michael Myers from Dr Loomis and Nurse Marion Chambers at the Smith Grove Sanitarium was an Illinois government-owned 1978 Ford LTD station wagon rented for two weeks of filming.

[93] Instead of utilizing a more traditional symphonic soundtrack, the film's score consists primarily of a piano melody played in a 10/8 or "complex 5/4" time signature, composed and performed by Carpenter.

"[98] In Halloween's end credits, Carpenter bills himself as the "Bowling Green Philharmonic Orchestra", but he also received assistance from composer Dan Wyman, a music professor at San José State University.

A new documentary was screened before the film at all locations, titled You Can't Kill the Boogeyman: 35 Years of Halloween, written and directed by HalloweenMovies.com webmaster Justin Beahm.

Another extra scene features Dr. Loomis at Smith's Grove examining Michael's abandoned cell after his escape and seeing the word "Sister" scratched into the door.

Pauline Kael wrote a scathing review in The New Yorker suggesting that "Carpenter doesn't seem to have had any life outside the movies: one can trace almost every idea on the screen to directors such as Hitchcock and Brian De Palma and to the Val Lewton productions" and musing that "Maybe when a horror film is stripped of everything but dumb scariness—when it isn't ashamed to revive the stalest device of the genre (the escaped lunatic)—it satisfies part of the audience in a more basic, childish way than sophisticated horror pictures do.

"[130] Susan Stark of the Detroit Free Press branded Halloween a burgeoning cult film at the time of its release, describing it as "moody in the extreme" and praising its direction and music.

[32] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film three and a half stars out of four and called it "a beautifully made thriller" that "works because director Carpenter knows how to shock while making us smile.

"[131] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post was negative, writing "Since there is precious little character or plot development to pass the time between stalking sequences, one tends to wish the killer would get on with it.

"[132] Lou Cedrone of The Baltimore Evening Sun referred to it as "tediously familiar" and whose only notable element is "Jamie Lee Curtis, whose performance as the intended fourth victim, is well above the rest of the film.

Claiming it encouraged audience identification with the killer, Martin and Porter pointed to the way "the camera moves in on the screaming, pleading victim, 'looks down' at the knife, and then plunges it into chest, ear, or eyeball.

Halloween helped to popularize the final girl trope, the killing off of characters who are substance abusers or sexually promiscuous,[155] and the use of a theme song for the killer.

[156][157] Due to its popularity, Halloween became a blueprint for success that many other horror films, such as Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street, followed, and that others like Scream gave nods towards.

The novelization adds aspects not featured in the film, such as the origins of the curse of Samhain and Michael Myers' life in Smith's Grove Sanatorium, which contradict its source material.