Hamon (swordsmithing)

In swordsmithing, hamon (刃文) (from Japanese, literally "edge pattern") is a visible effect created on the blade by the hardening process.

A true hamon, and many of its key features such as a nioi, have no direct translation into English, thus the Japanese terms are usually used when referring to clay-quenched blades.

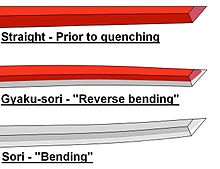

During the differential heat treatment, the clay coating on the back of the sword reduces the cooling speed of the red-hot metal when it is plunged into the water and allows the steel to turn into pearlite, a soft structure consisting of cementite and ferrite (iron) laminations.

On the other hand, the exposed edge cools very rapidly, changing into a phase called martensite, which is nearly as hard and brittle as glass.

This was by far the most popular style in every era and in every province, whereas the more complex patterns that were in themselves works of art tended to be reserved for the wealthy and elite.

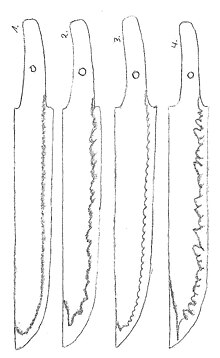

The two main groups are "undulating" or "wavy" (notare) and tooth-like or "zig-zag" (gunome), and these are often classified by the wavelength or breadth of the irregularities.

Koshi-no-hiraita midare consists of waves with wide valleys and steep crests, and were mainly found on Bizen swords of the Muromachi period.

The specific shape and style of the hamons were often unique and served as a sort of signature of the various swordsmithing schools or even for individual smiths that produced them.

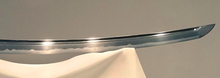

This leaves a pattern of bright streaks that jut a short distance away from the hamon, called niye, which give it a wispy, misty, or foggy appearance.

Iron-making technology was typically a closely guarded secret, but was eventually imported into Japan from China around 600 or 700 AD, albeit with only a small amount of information to build on, so the ancient smiths began by trying to reverse engineer the Chinese methods, coming up with very different processes in the end.

[11] According to legend, Amakuni Yasutsuna developed the process of differentially hardening the blades around the 8th century AD, around the time that the tachi (curved sword) became popular.

Sometimes low spots were cut into the clay to produce niye disconnected from the hamon in the center of the blade, creating the appearance of stars, clouds, wind-blown snowy peaks, or even birds in the sky.

The nioi is one of many features of Japanese swords that are sensitive to the viewing angle, seeming to appear and disappear when moved with respect to the light.

When viewed through a magnifying lens, the nioi appears as a sparkly line, being made up of many bright martensite grains which are surrounded by darker, softer pearlite.

[14][15] A flame-hardened temper line is easily discernible from a true hamon, which produces a nioi that provides a very tough boundary between the martensite and the pearlite.

Therefore, while flame hardening and temper lines are common in hand-made knives, they are rarely found in swords or weapons where a lot of shear and impact forces may be encountered.