Hand axe

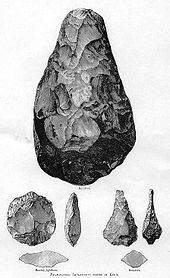

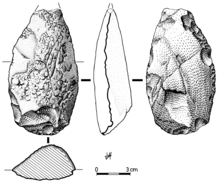

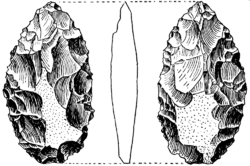

The most common hand axes have a pointed end and rounded base, which gives them their characteristic almond shape, and both faces have been knapped to remove the natural cortex, at least partially.

Examples of this include the "quasi-bifaces" that sometimes appear in strata from the Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian periods in France and Spain, the crude bifacial pieces of the Lupemban culture (9000 B.C.)

He claimed that a single design persisting across time and space cannot be explained by cultural imitation and draws a parallel between bowerbirds' bowers (built to attract potential mates and used only during courtship) and Pleistocene hominids' hand axes.

He proposed that in base settlements where it was possible to predict future actions and where greater control on routine activities was common, the preferred tools were made from specialized flakes, such as racloirs, backed knives, scrapers and punches.

[34] Analysis carried out by Domínguez-Rodrigo and co-workers on the primitive Acheulean site in Peninj (Tanzania) on a series of tools dated 1.5 mya shows clear microwear produced by plant phytoliths, suggesting that the hand axes were used to work wood.

[35] Among other uses, use-wear evidence for fire making has been identified on dozens of later Middle Palaeolithic hand axes from France, suggesting Neanderthals struck these tools with the mineral pyrite to produce sparks at least 50,000 years ago.

Yet, for most of the "Swiss Army knife" multipurpose suite of proposed uses (defleshing, scraping, pounding roots, and flake source), an easy-to-make shape would suffice – and indeed the simpler tools continued to be made.

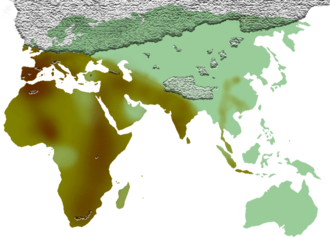

[50] In Europe and particularly in France and England, the oldest hand axes appear after the Beestonian Glaciation–Mindel Glaciation, approximately 750,000 years ago, during the so-called Cromerian complex.

The apogee of hand axe manufacture took place in a wide area of the Old World, especially during the Riss glaciation, in a cultural complex that can be described as cosmopolitan and which is known as the Acheulean.

However, Movius' hypothesis was proved incorrect when many hand axes made in Palaeolithic era were found in 1978 at Hantan River, Jeongok, Yeoncheon County, South Korea for the first time in East Asia.

With early hand axes, it is easy to improvise their manufacture, correct mistakes without requiring detailed planning, and no long or demanding apprenticeship is necessary to learn the necessary techniques.

Lastly, a hand axe represents a prototype that can be refined giving rise to more developed, specialised and sophisticated tools such as the tips of various projectiles, knives, adzes and hatchets.

Given the typological difficulties in defining the essence of a hand axe, it is important when analysing them to take account of their archaeological context (geographical location, stratigraphy, the presence of other elements associated with the same level, chronology etc.).

It is necessary to study their physical state to establish any natural alterations that may have occurred: patina, shine, wear and tear, mechanical, thermal and / or physical-chemical changes such as cracking, in order to distinguish these factors from the scars left during the tool's manufacture or use.

The links examined in this type of study start with the extraction methods of the raw material, then include the actual manufacture of the item, its use, maintenance throughout its working life, and finally its disposal.

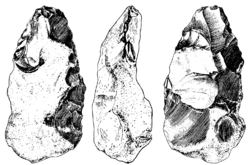

As hand axes are made from a tool stone's core, it is normal to indicate the thickness and position of the cortex in order to better understand the techniques that are required in their manufacture.

The hand axes arising from this methodology have a more classical profile with either a more symmetrical almond or oval shape and with a lower proportion of the cortex of the original core.

The main advantage of a soft hammer is that a flintknapper is able to remove broader, thinner flakes with barely developed heels, which allows a cutting edge to be maintained or even improved with minimal raw material wastage.

The most common were proposed by Bordes[67]: 51 and Balout:[12] A and o can be used to delineate the contour's cross section and to measure the angles of the edges (provided this is not an area covered in the stone's original cortex).

The most commonly used coefficients were established by Bordes for the morphological-mathematical classification of what he called "classic bifaces" (Balout proposed other, similar indices):[68] Hand axes are so varied that they do not actually have a single common characteristic… [...] Despite the numerous attempts to classify hand axes, some of which date to the beginning of the [20th] century... their study does not comply completely satisfactorily to any typological listThe following guide is strongly influenced by the possibly outdated and basically morphological "Bordes method" classification system.

This classification is particularly applicable to classic hand axes,[70][a] those that can be defined and catalogued by measuring dimensions and mathematical ratios, while disregarding nearly all subjective criteria.

[12] The triangular bifaces were initially defined by Henri Breuil as flat based, globular, covered with cortex, with two straight edges that converge at an acute apical zone.

In practice their dimensional ratios are equal to the ovoid tools, except that the elliptical bifaces are usually more elongated (L/m > 1.6) and their maximum width (m) is nearer to their mid length.

The difference between the two types is based on the latter's fine, light finishing with a soft hammer and in a morphology that suggests a specific function, possibly as the point of a projectile or a knife.

When he was not worried or fearful, this demigod acting in tranquillity, found the material in his surroundings to breathe life into his spirit.As Leroi-Gourhan explained,[87] it is important to ask what was understood of art at the time, considering the psychologies of non-modern humans.

He felt that he could recognize beauty in early prehistoric tools made during the Acheulean: It seems difficult to admit that these beings did not experience a certain aesthetic satisfaction, they were excellent craftsmen that knew how to choose their material, repair defects, orient cracks with total precision, drawing out a form from a crude flint core that corresponded exactly to their desire.

Their work was not automatic or guided by a series of actions in strict order, they were able to mobilize in each moment reflection and, of course, the pleasure of creating a beautiful object.Many authors who comment on the Westfield aspect of hand axes refer only to exceptional pieces.

[89]The discovery in 1998 of an oval hand axe of excellent workmanship in the Sima de los Huesos in the Atapuerca Mountains mixed in with the fossil remains of Homo heidelbergensis reignited this controversy.

Given that this is the only lithic remnant from this section of the site (possibly a burial ground), combined with the piece's qualities led it to receive special treatment, it was even baptized Excalibur and it became a star item.

[96] All the species associated with hand axes (from H. ergaster to H. neanderthalensis) show an advanced intelligence that in some cases is accompanied by modern features such as a relatively sophisticated technology, systems to protect against inclement weather (huts, control of fire, clothing), and certain signs of spiritual awareness (early indications of art such as adorning the body, carving of bones, ritual treatment of bodies, articulated language).

15.5 cm (6 in) tall [ 90 ] is finely crafted and made out of a rare stone, which may indicate symbolic meaning. [ 91 ]