Hanford Site

A citizen-led Hanford Advisory Board provides recommendations from community stakeholders, including local and state governments, regional environmental organizations, business interests, and Native American tribes.

[3] The Columbia and Yakima Rivers contain salmon, sturgeon, steelhead trout and bass, and wildlife in the area includes skunks, muskrats, coyotes, raccoons, deer, eagles, hawks and owls.

In September 1858 a military expedition under Colonel George Wright defeated the Native American tribes in the Battle of Spokane Plains to force compliance with the reservation system.

The Reclamation Act of 1902 provided for federal government participation in the financing of irrigation projects, and the population began expanding again, with small town centers at Hanford, White Bluffs and Richland established between 1905 and 1910.

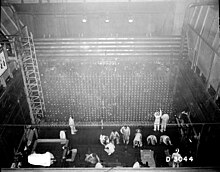

[24][25] Carpenter expressed reservations about building the reactors at Oak Ridge, Tennessee; with Knoxville only 20 miles (32 km) away, a catastrophic accident might result in loss of life and severe health effects.

Spreading the facilities at Oak Ridge out more would require the purchase of more land and the expansion needed was still uncertain; for planning purposes, six reactors and four chemical separation plants were envisioned.

Between December 18 and 31, 1942, just twelve days after the Metallurgical Laboratory team led by Enrico Fermi started up Chicago Pile 1, the first nuclear reactor, a three-man party consisting of Colonel Franklin T. Matthias and DuPont engineers A. E. S. Hall and Gilbert P. Church inspected the most promising potential sites.

Federal Judge Lewis B. Schwellenbach issued an order of possession under the Second War Powers Act the following day, and the first tract was acquired on March 10.

[38] Because construction plans had not yet been drawn up, and work on the site could not immediately commence, Groves decided to postpone the taking of the physical possession of properties under cultivation to allow farmers to harvest the crops they had already planted.

Matthias gave assurances that Native American graves would be treated with respect, but it would be fifteen years before the Wanapum people were allowed access to mark the cemeteries.

[47] DuPont advertised for workers in newspapers for an unspecified "war construction project" in southeastern Washington, offering an "attractive scale of wages" and living facilities.

[64][65] Irradiated fuel slugs were transported by rail on a special railroad car operated by remote control to huge remotely-operated chemical separation plants about 10 miles (16 km) away.

Once they began processing irradiated slugs, the machinery became so radioactive that it would be unsafe for humans ever to come in contact with it, so the engineers devised methods to allow for the replacement of components via remote control.

Running the reactors continuously at full power had resulted in the Wigner effect, swelling of the graphite due to the displacement of the atoms in its crystalline structure by collisions with neutrons.

Each battery had four guns, which were deployed in sandbagged revetments on a 20-acre (8.1 ha) site with wooden, prefabricated metal and containing barracks, latrines, mess halls, motor pools, radars and administrative facilities.

The following year the guns were augmented by Nike Ajax missiles, which were deployed at three sites on Wahluke Slope and one on what is now the Fitzner-Eberhardt Arid Lands Ecology Reserve.

[159] A serious accident occurred at the 242-Z Waste Treatment Facility in 1976, when the contents of a glove box containing americium and plutonium exploded, seriously injuring an operator, Harold McCluskey.

The dual-purpose concept involved trade-offs that made both purposes less efficient: power required a steam turbine, but high water temperatures risked slug failure.

[179][180] In January 1969, AEC chairman Glenn Seaborg, under pressure from the newly elected Nixon administration to cut costs, announced that the three reactors built in the 1950s, C, KE and KW, would be shut down in 1969 and 1970.

As a result of this concentration of specialized skills, the Hanford Site attempted to diversify its operations to include scientific research, test facilities, and commercial nuclear power production.

[226] The Columbia Generating Station is a 1,207 MW commercial nuclear power plant located on the Hanford Site 10 miles (16 km) north of Richland and operated by Energy Northwest,[215][227] as the WPPSS has been known since 1998.

[237] The plutonium separation process resulted in the release of radioactive isotopes into the air, which were carried by the wind throughout southeastern Washington and into parts of Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and British Columbia.

In response to an article in the Spokane Spokesman Review in September 1985, the DOE announced it would declassify environmental records and, in February 1986, released 19,000 pages of previously unavailable historical documents about Hanford's operations.

[242][243] In February 2013, Washington Governor Jay Inslee announced that a tank storing radioactive waste at the site had been leaking liquids on average of 150 to 300 US gallons (570 to 1,140 L) per year.

[245] While major releases of radioactive material ended with the reactor shutdown in the 1970s and many of the most dangerous wastes are contained, there were continued concerns about contaminated groundwater headed toward the Columbia River and about workers' health and safety.

[249] On November 19, 2014, the attorney general of Washington, Bob Ferguson, said the state planned to sue the DOE and its contractor to protect workers from hazardous vapors at Hanford.

The cleanup effort was focused on three outcomes: restoring the Columbia River corridor for other uses, converting the central plateau to long-term waste treatment and storage, and preparing for the future.

A citizen-led Hanford Advisory Board provides recommendations from community stakeholders, including local and state governments, regional environmental organizations, business interests, and Native American tribes.

[264][265] In 2000 the DOE awarded a $4.3 billion contract to Bechtel, a San Francisco-based construction and engineering firm, to build a vitrification plant to combine the dangerous wastes with glass to render them stable.

Washington state officials expressed concern about the budget cuts, as well as missed deadlines and recent safety lapses at the site, and threatened to file a lawsuit alleging that the DOE was in violation of environmental laws.