Hans Baluschek

After the Franco-Prussian War and foundation of the German Empire in 1871, Franz became an independent engineer for the railways, and lived for a time in the much smaller town of Haynau (now Chojnów, Poland).

[2] In 1876 the family, with 6-year-old Hans, moved to Berlin, where during the next decade they changed their residence five times, living in a succession of newly built apartments developed expressly for workers.

[2] In 1887, his father took a job with the railway on the large German island of Rügen, and the family moved to nearby Stralsund, where Baluschek completed his Gymnasium education.

[2] After graduating, Baluschek was admitted to the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste), where he became acquainted with the German painter Martin Brandenburg, with whom he was to maintain a lifelong friendship.

Meanwhile, he was reading the left-leaning works of Gerhart Hauptmann, Tolstoy, Ibsen, Johannes Schlaf und Arno Holz and was heavily influenced by the literature of Naturalism.

For example, his 1894 work Noon (Mittag) depicts women with children bringing lunch baskets to their men employed at the factories, and evokes the "endless drudgery" of working-class life, with its constant repetition of daily tasks.

[3] With Railwayman's Evening Free (Eisenbahner-Feierabend) in 1895, this theme is represented by an individual worker who returns exhausted from work against a backdrop of railroad installations, smoke stacks and overhead tram wires, and is greeted by anxious children.

At the time Baluschek maintained a friendly relationship with the avant-garde poet Richard Dehmel, known for poems such as The Working Man (Der Arbeitmann) and Fourth Class (Vierter Klasse).

Baluschek developed relationships with several left-leaning writers, among them the poet and playwright Arno Holz, best known for Phantasus (1898), a poetry collection describing the starving artists of the Wedding district of Berlin.

His portrayal of the inhumane living environment and bleak working conditions behind society's often glitzy facade showed, said art critic Willy Pastor, "that more was hidden behind the scenes than a cozy story.

In Here a family can make coffee (1895), the worn and lined faces of the women evoke a similar mood, while in Tingle-tangle (1890), the patriotically decorated interior of a nightspot contrasts with a risqué performance by a prostitute.

In Berlin Amusement Park, a cigarette-smoking adolescent worker contrasts with a child blowing up a balloon, and the watercolor New Houses (1895) depicts monotonous rows of empty new tenements near a factory.

[3] At the end of the 19th century the Berlin art scene split into two camps due to the dissatisfaction of innovative artists with officially sanctioned exhibits in the city's museums.

The Secession also enlisted German artists Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Nagel and Heinrich Zille, and championed French impressionism, pointillism and symbolism.

For example, Waldemar Count von Oriola, a Reichstag deputy from the National Liberal Party, termed his work a "rampant travesty of aesthetic norms.

[3] Baluschek was profiled in 1904 as the first in a monograph series by Hermann Esswein titled Modern Illustrators, which later included Edvard Munch, Toulouse-Lautrec and Aubrey Beardsley.

Germany's declaration of war on Russia and France led to a release of pent-up tensions that had been building for decades due to strained international relations and repeated crises.

[9] Baluschek's patriotic stance was at odds with his longstanding aversion to the Hohenzollern monarchy, but perhaps reflected an underlying resentment of the pervasive influence of French art in Germany.

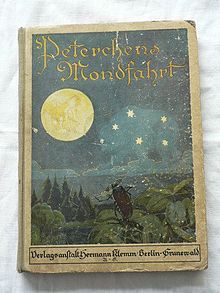

[9] For Baluschek the artist, the following years were dominated by illustrations of fairytales, and those he contributed to Little Peter's Journey to the Moon (Peterchens Mondfahrt) in 1919 are still considered classics of children's literature.

[11] Baluschek illustrated other children's books, among them What the Calendar Tells Us (Was der Kalender erzählt), Into Fairytale-land (In's Märchenland) and About Little People, Little Animals, and Little Things (Von Menschlein, Tierlein, Dinglein), appearing in 1919, 1922 and 1924 respectively.

[12] Predictably, after the Nazis came to power in January 1933 they branded Baluschek a "Marxist artist" and classified his work as so-called degenerate art (entartete Kunst).