Phonological history of English close front vowels

The spellings that became established in Early Modern English are mostly still used today, but the qualities of the sounds have changed significantly.

In Modern English, the short form has generally become standard, but the spelling ⟨ea⟩ reflects the formerly-longer pronunciation.

During the Great Vowel Shift, the normal outcome of /iː/ was a diphthong, which developed into Modern English /aɪ/, as in mine and find.

), but some borrowed words have a single ⟨e⟩ (legal, decent, complete), ⟨ei⟩, or otherwise (receive, seize, phoenix, quay).

In Received Pronunciation, a diphthong /ɪə/ has developed (and by non-rhoticity, the /r/ is generally lost unless there is another vowel after it) and so beer and near are /bɪə/ and /nɪə/, and nearer (with /ɪə/) remains distinct from mirror (with /ɪ/).

[8] Another development is that bisyllabic /iːə/ may become smoothed to the diphthong [ɪə] (with the change being phonemic in non-rhotic dialects, so /ɪə/) in certain words, which leads to pronunciations like [ˈvɪəkəl], [ˈθɪətə] and [aɪˈdɪə] for vehicle, theatre/theater and idea, respectively.

[12] The short mid vowels have also undergone lowering and so the continuation of Middle English /e/ (as in words like dress) now has a quality closer to [ɛ] in most accents.

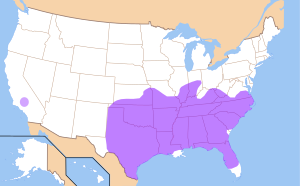

A study[16] of the written responses of American Civil War veterans from Tennessee, together with data from the Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States and the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle South Atlantic States, shows that the prevalence of the merger was very low up to 1860 but then rose steeply to 90% in the mid-20th century.

Central and southern Indiana is dominated by the merger, but there is very little evidence of it in Ohio, and northern Kentucky shows a solid area of distinction around Louisville.

However, in the West, there is sporadic representation of merged speakers in Washington, Idaho, Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado.

However, the most striking concentration of merged speakers in the west is around Bakersfield, California, a pattern that may reflect the trajectory of migrant workers from the Ozarks westward.

Wells, however, suggests that the non-rhyming of words like kit and bit, which is particularly marked in the broader accents, makes it more satisfactory to consider [ɪ̈] to constitute a different phoneme from [ɪ ~ i], and [ɪ̈] and [ə] can be regarded as comprising a single phoneme except for speakers who maintain the contrast in weak syllables.

There is also the issue of the weak vowel merger in most non-conservative speakers, which means that rabbit /ˈræbət/ (conservative /ˈræbɪt/) rhymes with abbott /ˈæbət/.

[25] The weak vowel is consistently written ⟨ə⟩ in South African English dialectology, regardless of its precise quality.

In speakers with this merger, the words abbot and rabbit rhyme, and Lennon and Lenin are pronounced identically, as are addition and edition.

The merger also affects the weak forms of some words and causes unstressed it, for instance, to be pronounced with a schwa, so that dig it would rhyme with bigot.

In New Zealand English, the merger is complete, and indeed, /ɪ/ is very centralized even in stressed syllables and so it is usually regarded as the same phoneme as /ə/ although in -ing, it is closer to [i].

In traditional Southern American English, the merger is generally not present, and /ɪ/ is also heard in some words that have schwa in RP, such as salad.

[30] In traditional RP, the contrast between /ə/ and weak /ɪ/ is maintained, but that may be declining among modern standard speakers of southern England, who increasingly prefer a merger, specifically with the realisation [ə].

[31][32] The merger is not complete in Scottish English, whose speakers typically distinguish except from accept, but the latter can be phonemicized with an unstressed STRUT: /ʌkˈsɛpt/ (as can the word-final schwa in comma /ˈkɔmʌ/) and the former with /ə/: /əkˈsɛpt/.

In RP, /ə/ is now often heard in place of /ɪ/ in endings such as -ace (as in palace); -ate (as in senate); -less, -let, for the ⟨i⟩ in -ily; -ity, -ible; and in initial weak be-, de-, re-, and e-.

In the third edition of the OED, that symbol is used in the transcription of words (of the types listed above) that have free variation between /ɪ/ and /ə/ in RP.

In non-rhotic varieties with the shift, it also encompasses the unstressed syllable of letters with the stressed variant of /ɪ/ being realized with a schwa-like quality [ə].

[39][40] There are no homophonous pairs apart from those caused by the weak vowel merger, but a central KIT tends to sound like STRUT to speakers of other dialects and so Australians accuse New Zealanders of saying "fush and chups", instead of "fish and chips", which in an Australian accent sounds close to "feesh and cheeps".

That affects the final vowels of words such as happy, city, hurry, taxi, movie, Charlie, coffee, money and Chelsea.

It may also apply in inflected forms of such words containing an additional final consonant sound, such as cities, Charlie's and hurried.

The tense [i] variant, however, is now established in as the norm in Modern RP and General American, and is also the usual form in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, in southern England and in some northern English regions (such as Merseyside, Hull and the entire North East).

They may also be considered to represent a neutralization between the two phonemes, but for speakers with the tense variant, there is the possibility of contrast in such pairs as taxis and taxes (see English phonology – vowels in unstressed syllables).

[48][49] Cruttenden (2014) regards the tense variant in modern RP as still an allophone of /ɪ/ on the basis that it is shorter and more resistant to diphthongization than is /iː/.

For some speakers, it occurs only before voiceless consonants, and pairs like met, mat, bet, bat are homophones, but bed, bad or med, mad are kept distinct.