Harriet Powers

Harriet Powers (October 29, 1837 – January 1, 1910)[1] was an American folk artist and quilter born into slavery in rural northeast Georgia.

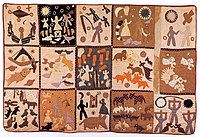

Powers used traditional appliqué techniques to make quilts that expressed local legends, Bible stories, and astronomical events.

After the American Civil War and emancipation, she and her husband became landowners by the 1880s, but lost their land due to financial problems.

[6][7] By the 1880s Powers and her family owned four acres of land and ran a small farm in Clarke County.

[4][5][7] After some financial difficulty, Armstead began to slowly sell off tracts of land in the early 1890s, and he ultimately defaulted on his taxes.

[4][5] It was here that Jennie Smith, an artist and art teacher from the Lucy Cobb Institute, saw the quilt, which she found to be remarkable,[16] and asked to purchase it.

[5] Powers vividly explained the imagery on the quilt to Smith– who recorded these explanations, adding notes of her own, in her personal diary.

[5] Powers visually communicated with her narrative quilts in themes from her own experience and the techniques from the age-old crafts of African Americans.

[citation needed] Whatever its origins, the piece was presented to the Reverend Charles Cuthbert Hall of New York City, who was serving as the vice-chairman of the University's board of trustees at the time.

The reverend's heirs sold the quilt to collector Maxim Karolik, who then donated it to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

[4][20] Looking at the panels from left to right, top to bottom, the stories represented are: Jennie Smith, a young local artist who had studied abroad, saw the quilt at the Athens Cotton Fair of 1886.

She later wrote that she was taken with the quilt because, "[Powers's] style is bold and rather on the impressionist's order while there is a naivete of expression that is delicious.

Powers visited the quilt on several occasions while Smith owned it, demonstrating its special significance in her life.

These groups believed strongly that, if reproductions were going to be made, they should be produced by American quilting companies to help support the craft in the U.S.

They agreed to prohibit sale of quilt reproductions in museum gift shops or any type of catalogue, and contracted for quilt reproductions with two domestic companies, Cabin Creek Quilters in Appalachia and Missouri Breaks, a group based on the Lakota Sioux reservation.

[27] To prevent such controversies in the future, the Smithsonian additionally began to hold public forums that fostered discussion and further research about ethical practices as related to artistic reproductions.

The quilt was created as a gesture of appreciation for Hall’s contributions to Atlanta University, an institution established to educate African Americans.

Collectors Maxim and Martha Karolik purchased the work in 1964, donating it to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in a bequest.

Both quilts are hand and machine stitched, using appliqué and piecework techniques that demonstrate both African-American and African influences.

According to her notes, for the Leonid or falling stars square, Powers said, "The people were frightened and thought that the end of time had come.

"[33] Another panel illustrates the 'dark day' May 19, 1780 (now identified as a historically dense smoke over North America caused by Canadian Wildfires).

[6] Art historians have identified similarities between West African appliqué wall hangings and Powers's works.

Similar to the appliquéd textiles of Benin, Powers's work feature standardized symbols with little variation.

[20] Author Floris Barnett Cash suggests that Powers's interest in celestial scenes, religious stories, and astronomical occurrences reflected interchanges within the Black community where she lived.

Researchers have learned that Powers was literate, but she might also have used her quilts as teaching tools, as many people in her community were likely unable to read.

[35] In 2005, University of Georgia graduate student Cat Holmes rediscovered the joint headstone for Powers and her husband, Armsted, which over the years had been obscured by overgrown vegetation.

On Christmas Eve 2004, Holmes and her husband, David Berle, a University of Georgia horticulture professor, who had been assisting with restoration efforts for the cemetery, were searching in a "still uncleared" area.

[36] In December 2023, a new, commemorative memorial for Harriet and Armstead Powers was dedicated at the Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery.

[3] In October 2010, organizations in Athens, Georgia, produced several events related to the theme "Hands That Can Do: A Centennial Celebration of Harriet Powers."

[40][41] Athens-Clarke County Mayor Heidi Davison issued a proclamation naming October 30, 2010, as Harriet Powers Day.