Harris's List of Covent Garden Ladies

As the public's opinion began to turn against London's sex trade, and with reformers petitioning the authorities to take action, those involved in the release of Harris's List were in 1795 fined and imprisoned.

Allegedly an exposé of the capital's sex trade and usually attributed to John Garfield, it lists streets in which prostitutes might have been found, and the locations of brothels in areas like Fleet Lane, Long Acre and Lincoln's Inn Fields.

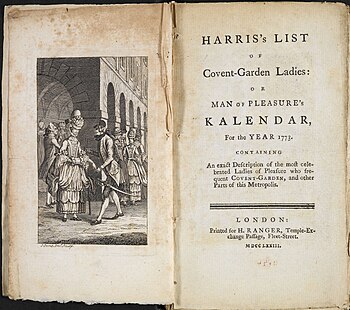

[9] Several editions of Harris's List opens with a frontispiece showing a mildly erotic stock image opposite the title page, which, from the 1760s to 1780s, is followed by a lengthy commentary on prostitution.

"[11] At a basic level, the entries in Harris's List detail each woman's age, her physical appearance (including the size of her breasts), her sexual specialities, and sometimes a description of her genitals.

[13][nb 1] The types of sex worker the lists present vary from "low-born errant drabs",[10] to prominent courtesans like Kitty Fisher and Fanny Murray; later editions contain only "genteel mannered prostitutes worthy of praise".

[10] The charms of a Mrs Dodd, who lived at number six Hind Court in Fleet Street, were listed in 1788 as "reared on two pillars of monumental alabaster", continuing: "the symmetry of its parts, its borders enriched with wavering tendrils, its ruby portals, and the tufted grove, that crowns the summit of the mount, all join to invite the guest to enter.

"[15] In the same edition, a similarly lurid description precedes the latter part of Miss Davenport's entry, which concludes: "Her teeth are remarkably fine; she is tall, and so well proportioned (when you examine her whole naked figure, which she will permit you to do, if you perform the Cytherean Rites like an able priest) that she might be taken for a fourth Grace, or a breathing animated Venus de Medicis ... she has a keeper (a Mr. Hannah) both kind and liberal; notwithstanding which, she has no objection to two supernumerary guineas.

"[16] Miss Clicamp, of number two York Street near Middlesex Hospital, is described as "one of the finest, fattest figures as fully finished for fun and frolick as fertile fancy ever formed ... fortunate for the true lovers of fat, should fate throw them into the possession of such full grown beauties.

"[17] More characteristic of Harris's List though, is the 1764 entry for Miss Wilmot, which tells of an amorous encounter with King George III's brother, the Duke of York: He gazed on her a while with eyes of transport and fondness, and gave her a world of kisses; at the close of which, in a pretended struggle, she contrived matters so artfully, that the bed-cloaths having fallen off, her naked beauties lay exposed at full length.

The coral-lipped mouth of love seemed with kind movements to invite, nay, to provoke an attack; while her sighs, and eyes half-closed, denoted that no farther resistance was intended.

[19] The women's route into the sex trade, as described by the lists, is usually ascribed to youthful innocence, with tales of young girls leaving their homes for the promises of men, only to be abandoned once in London.

[20] The "old urban legend"[21] of young girls being apprehended from the crowd by devious bawds is illustrated by William Hogarth's A Harlot's Progress,[22] but although in reality such stories were not unheard of, women entered into prostitution for a variety of reasons, often mundane.

Mrs Cornish's genteel nature was, on occasion, interrupted by "a volley of small shot", and Miss Johnson's proclivity towards "vulgarity of expression and a coarseness of manner" apparently suffered no shortage of admirers.

Mrs Russell, attractive to "a number of clients among the youth, who are fond of beholding that mouth of the devil from whence all corruption issueth", was admired for her "vulgarity more than any thing else, she being extremely expert at uncommon oaths".

Mrs William's entry of 1773 is full of remorse, her having returned home "so intoxicated so as not to be able to stand, to the no small amusement of her neighbors", and Miss Jenny Kirbeard had, in 1788, a "violent attachment to drinking".

Not all entries were disapproving though; Mrs Harvey would, in 1793, "often toss off a sparkling bumper," while remaining "a lady of great sensibility ... not a little clever in the performance of the act of friction.

Sex workers may have paid money to appear in the lists, and in Denlinger's view such commentary may indicate a degree of annoyance on the writer's part, the women concerned perhaps having refused to pay.

[31] Some listings also imply a degree of dissatisfaction on the part of the customer; in the 1773 edition, Miss Dean exhibited "great indifference" while entertaining her client, busying herself by cracking nuts while he was "acting his joys".

Born perhaps around 1720–1730,[37] Harris apparently had expert knowledge of sex workers working in Covent Garden and beyond, as well as access to rented rooms and premises for his clients' use.

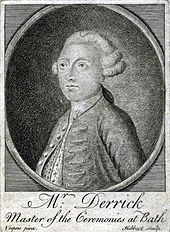

[39] Printed and published by the pseudonymous H. Ranger, responsible for such works as Love Feasts; or the different methods of courtship in every country, throughout the known world,[2] the proceeds from the hugely successful first edition enabled Derrick to repay his debts, thereby freeing himself from a spunging house.

[54] The area was noted for its "great numbers of female votaries to Venus of all ranks and conditions", while another author distinguished Covent Garden as "the chief scene of action for promiscuous amours.

Elizabeth Denlinger includes a similar sentiment in her essay, "The Garment and the Man": "This varied display of women to satisfy the 'great itch' ... is a fundamental aspect of the sphere to which Harris's List offered British men a carte d'entrée".

[59] Rubenhold writes that the variability in the descriptions of prostitutes over the years the list was published defy "all attempts to categorise it as either exclusively up-market or simply middle of the road.

"[60] She suggests that the annual's purpose was to "conduct the desirous to the embrace of a prostitute",[10] and that its prose was designed for "solitary sexual enjoyment"[2] (H. Ranger also sold back-issues of Harris's List).

[63] Attitudes towards sex work hardened at the end of the 18th century, with many viewing prostitutes as indecent and immoral,[64] and it was in this atmosphere that Harris's List met its demise.

Along with the anonymously written Fifteen Plagues of a Maidenhead (1707), Garfield and Curll's works were involved in cases that helped form the 18th-century legal concept of "obscene libel"—which was a marked change from the previous emphasis on controlling sedition, blasphemy and heresy, traditionally the ecclesiastical courts' province.