Harry Chauvel

General Sir Henry George Chauvel, GCMG, KCB (16 April 1865 – 4 March 1945) was a senior officer of the Australian Imperial Force who fought at Gallipoli and during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I.

Promoted to colonel in 1913, Chauvel became the Australian representative on the Imperial General Staff but the First World War broke out while he was still en route to the United Kingdom.

[7] In July 1899, the Premier of Queensland, James Dickson, offered a contingent of troops for service in South Africa in the event of war between the British Empire, and the Boer Transvaal Republic and Orange Free State.

In 1902, Chauvel was appointed to command of the 7th Commonwealth Light Horse, a unit newly raised for service in South Africa,[14] with the local rank of lieutenant colonel.

He recommended that Australian troops improve their discipline in the field, called for stronger leadership from officers, and emphasised the need for better organisation for supply and for timely and efficient medical evacuation.

[19] On 3 July 1914, he sailed for England with his wife and three children to replace Colonel James Gordon Legge as the Australian representative on the Imperial General Staff.

On reporting for duty at the War Office in mid-August 1914, Chauvel was given a cable directing him to assume command of the 1st Light Horse Brigade of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) when it arrived in the United Kingdom.

Convinced that the huts would not be ready on time, and that Australian troops would therefore have to spend a winter on Salisbury Plain under canvas, Chauvel persuaded the High Commissioner for Australia in London, former Prime Minister Sir George Reid, to approach Lord Kitchener with an alternate plan of diverting the AIF to Egypt, which was done.

Accompanied by Major Thomas Blamey, Chauvel sailed for Egypt on the ocean liner SS Mooltan on 28 November 1914, arriving at Port Said on 10 December 1914.

The British commander in Egypt, Lieutenant General Sir John Maxwell, elected instead to ship the mounted brigades to Anzac Cove intact.

Chauvel responded by bringing up reserves and appointing a temporary post commander, Lieutenant Colonel H. Pope, with orders to drive the Turks out at all costs.

Always cool, and looking far enough ahead to see the importance of any particular fight in its proper relation to the war as a whole, he was brave enough to break off an engagement if it promised victory only at what he considered an excessive cost to his men and horses.

Under great pressure, Chauvel maintained his position until Brigadier-General Edward Chaytor's New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade arrived after being released by Lawrence.

[50] In October 1916 Major General Sir Charles Macpherson Dobell, a Canadian officer with broad experience in fighting colonial wars took over command of Eastern Force.

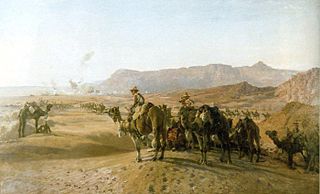

Its advanced troops – including Chauvel's Anzac Mounted Division – became part of the newly formed Desert Column under Major-General Sir Philip Chetwode, a British cavalry baronet.

[53] "Chauvel's leadership," wrote Henry Gullett, "was distinguished by the rapidity with which he summed up the very obscure Turkish position in the early morning, and by his judgement and characteristic patience in keeping so much of his force in reserve until the fight developed sufficiently to ensure its most profitable employment.

A British regular army officer fresh from experience in the Senussi Campaign, Major General Sir H. W. Hodgson, was appointed to command, with an all-British staff.

[63] Dobell launched the Second Battle of Gaza in April 1917 with a full scale frontal assault supported by naval gunfire, tanks and poison gas.

"[71] On being told of the appointments, in a letter dated 12 August 1917 Chetwode wrote to congratulate Chauvel, "I cannot say how much I envy you the command of the largest body of mounted men ever under one hand – it is my own trade – but Fate has willed it otherwise.

[75] For this decisive victory, and the subsequent capture of Jerusalem, Chauvel was mentioned in despatches twice more,[76][77] and appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in the 1918 New Year Honours List.

Lieutenant Colonel T. E. Lawrence later lampooned this as a "triumphal entry" but it was actually a shrewd political stroke,[86] freeing Chauvel's forces to advance another 300 km to Aleppo, which was captured on 25 October.

He warned, for example, that if war came, soldiers would "be subject to the unfair handicap and the certainty of increased loss of life which inferiority in armament and shortage of ammunition must inevitability entail".

[98] Looking back from the perspective of World War II, historian Gavin Long noted that Chauvel's annual reports were "a series of wise and penetrating examinations of Australian military problems of which, however, little notice was taken".

Ian and Edward arrived from India on leave, Alexander Godley came from Britain, and Richard Howard-Vyse as chief of staff to Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester.

When the Dominion troops assembled at Buckingham Palace to receive their King George VI Coronation Medals, Chauvel led the parade, with Howard-Vyse as his chief of staff.

[107] During the Second World War, Chauvel was recalled to duty as Inspector in Chief of the Volunteer Defence Corps (VDC), the Australian version of the British Home Guard.

Following Brudenell White's death in the Canberra air disaster, Prime Minister Robert Menzies turned to Chauvel for advice on a successor as Chief of the General Staff.

During the war, Chauvel's son Ian served as staff officer in the Italian campaign, while Edward was posted to New Guinea to learn about jungle warfare from the Australian Army.

Chauvel's daughter Eve joined the Women's Royal Australian Naval Service and spent a day in a lifeboat in the North Atlantic after her ship was torpedoed by a U-boat.

Harry Chauvel was portrayed in film: by Bill Kerr in The Lighthorsemen (1987), which covered the exploits of an Australian cavalry regiment during the Third Battle of Gaza; by Ray Edwards in A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia (1990), which took place around the 1919 Paris peace conference; and by Colin Baker in the 1992 Young Indiana Jones TV movie Daredevils of the Desert, another retelling of the Third Battle of Gaza from the director of The Lighthorsemen.