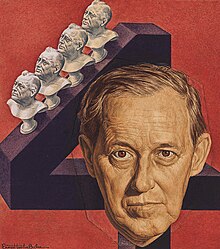

Harry Hopkins

In 1931, New York Temporary Emergency Relief Administration chairman Jesse I. Straus hired Hopkins as the agency's executive director.

His successful leadership of the program earned the attention of then-New York Governor Roosevelt, who brought Hopkins into his federal administration after he won the 1932 presidential election.

As Roosevelt's closest confidant, Hopkins assumed a leading foreign policy role after the outset of World War II.

From 1940 until 1943, Hopkins lived in the White House and assisted the president in the management of American foreign policy, particularly toward the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union.

He traveled frequently to the United Kingdom, whose prime minister, Winston Churchill, recalled Hopkins in his memoirs as a "natural leader of men" with "a flaming soul."

His father, born in Bangor, Maine, ran a harness shop (after an erratic career as a salesman, prospector, storekeeper, and bowling-alley operator), but his real passion was bowling, and he eventually returned to it as a business.

Anna Hopkins, born in Hamilton, Ontario, had moved at an early age to Vermillion, South Dakota, where she married David.

Shortly after Harry was born, the family moved successively to Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Kearney and Hastings, Nebraska.

[1] In 1915, New York City Mayor John Purroy Mitchel appointed Hopkins executive secretary of the Bureau of Child Welfare which administered pensions to mothers with dependent children.

[2] Hopkins moved to New Orleans where he worked for the American Red Cross as director of Civilian Relief, Gulf Division.

He feuded with Harold Ickes, who ran a rival program, the Public Works Administration, which also created jobs by contracting private construction firms, which did not require applicants to be unemployed or on relief.

[7] In the years after he resigned, Hopkins expressed pride in the WPA's key role in building internment camps for Japanese Americans.

[13] Initially, Hopkins was skeptical of the news until Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Harold Rainsford Stark called a few minutes later to confirm Pearl Harbor had in fact been attacked.

During the war years, Hopkins acted as Roosevelt's chief emissary to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

'"[14] [15] Hopkins became the administrator of the Lend-Lease program, under which the United States gave to Britain and Soviet Union, China, and other Allied nations food, oil, and materiel including warships, warplanes and weaponry.

Hopkins had a major voice in policy for the vast $50 billion Lend-Lease program, especially regarding supplies, first for Britain and then, upon the German invasion, the Soviets.

Newspapers ran stories detailing sumptuous dinners that Hopkins attended while he was making public calls for sacrifice.

Hopkins briefly considered suing the Chicago Tribune for libel after a story that compared him to Grigory Rasputin, the famous courtier of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, but he was dissuaded by Roosevelt.

A particularly striking example of bad faith was Moscow's refusal to allow American naval experts to see the German experimental U-boat station at Gdynia captured on March 28, 1945, and thus to help the protection of the very convoys that carried Lend-Lease aid.

As the top American decision maker in Lend-Lease, he gave priority to supplying the Soviet Union, despite repeated objections from Republicans.

George Racey Jordan testified to the House Un-American Activities Committee in December 1949 that Hopkins passed nuclear secrets to the Soviets.

[26] Verne W. Newton, the author of FDR and the Holocaust, said that no writer discussing Hopkins has identified any secrets disclosed or any decision in which he distorted American priorities to help communism.

Mark says that at the time, any actions were taken specifically to help the American war effort and to prevent the Soviets from making a deal with Hitler.

The historian Robert Conquest wrote that "Hopkins seems just to have accepted an absurdly fallacious stereotype of Soviet motivation, without making any attempt whatever to think, or to study the readily available evidence, or to seek the judgement of the knowledgeable.

What remained of Hopkins's stomach struggled to digest proteins and fat, and a few months after the operation, doctors stated that he had only four weeks to live.

[41] Though his death has been attributed to his stomach cancer, some historians have suggested that it was the cumulative malnutrition related to his post-cancer digestive problems.

There is a house on the Grinnell College campus named after him and his childhood home, with a plaque, is located at Sixth Avenue and Elm Street.