Hartford City Glass Company

By 1901, the county had over 1,100 people employed at manufacturing plants in small communities such as Hartford City, Indiana.

[5] Like many Indiana communities during the gas boom, Hartford City’s leaders sought to take advantage of their newfound energy resource.

[6] Manufacturers that used high quantities of energy were especially attracted to no-cost or low-cost natural gas sites, and glassmaking was one of those energy-consuming industries.

[Note 1] In 1878, glassmaker Richard Heagany organized a window glass plant in New York and was the factory's superintendent.

[13] In 1886, he moved to Kokomo, Indiana, and opened the first window glass plant in the region to use natural gas as a fuel source.

[16] Conger was a Civil War veteran who invested in companies in Ohio and Indiana (including in Kokomo).

Heagany submitted his resignation at the August 1899 board meeting, retiring after 42 years in the glass business.

The glass blower led a small production crew that included skilled and unskilled workers.

At older plants, the glass blower's workstation was adjacent to a ceramic pot located inside the furnace.

Each pot contained molten glass created by melting a batch of ingredients that included sand, soda, and lime.

[13] In Hartford City, Heagany again relied upon Belgian workers for the skilled positions in his glass works.

[38] During the early 1900s, the local Blackford County Gazette claimed to be the "only newspaper in State that prints French and circulates among the window glass and iron workers, the highest paid skilled mechanics in the world.

Hartford City's Presbyterian Church, which is now part of the National Register of Historical Places, was built one block north of the courthouse in 1894—and features large stained glass windows imported from Belgium.

[40] Construction of Hartford City's new glass works was completed in early January 1891, and production started shortly thereafter.

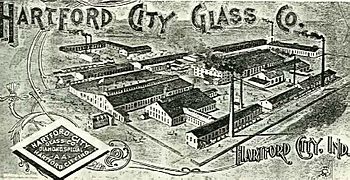

[42] The glass works was located on Hartford City's south side, and originally occupied 12 acres (4.9 ha).

[43] Natural gas was the plant's original fuel source for both the furnace used to make the glass and the ovens used to gradually cool it.

[Note 3] With its size, newest technology, and newly built facilities, the plant was "said to be the largest and best arranged window glass works in the world.

[Note 4] Initial production at the Hartford City plant continued until June, when the works was shut down to decrease inventories.

In the case of the first year's shutdown for the Hartford City Glass works, production was restarted in October.

"[57] Two major concerns voiced by management to community leaders were adequate fire protection and housing for the workers.

[62] By September (without the capacity expansion), the plant had a payroll of $45,000 (over $1.1 million in 2012 dollars) per month, and employed 500 glass workers.

[63] In 1896, the plant employed 550 people, and produced about 2 million square feet of window glass per month.

Refinements to the machine and glass-making process were made at the Hartford City works by plant manager Harry G. Slingluff.

Production records for the entire company were set at the Hartford City plant in 1905 and 1907—using the Lubbers machines.

It could make windows four times as large because a larger cylinder was extracted from the tank of molten glass.

[78] The Belgian portion of Hartford City's glassmaking workforce was dramatically reduced because of two factors: the glass-blowing machine replaced human glass blowers; and Belgians had difficulty returning from summer vacations in their European homeland after the start of World War I.

"[83] During the beginning of the 20th century, competitors of the American Window Glass trust used a different approach to gain a technological advantage.

Competitors such as American inventor Irving W. Colburn began working on a machine that produced window glass using a different process.

Although he filed for bankruptcy in 1912, his patents were purchased by Edward Drummond Libbey and Michael J. Owens—who hired Colburn to continue work on the machine.

[84][Note 7] Because of the improved technology and processes utilized by competitors, many of the American Window Glass patents, and much of its machinery, became obsolete.