Bartlett-Hayward Company

The company engaged initially in the production of Latrobe stoves, but by the end of the nineteenth century, its Pigtown complex was the largest iron foundry in the United States, with a diverse output including cast-iron architecture, steam heating equipment, machine parts, railroad engines and piston rings.

[7][8] In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Bartlett-Hayward expanded to become the country's largest producer of gas holders,[9][10] sending ironworkers far and wide to erect them, mostly for municipal and industrial gasworks.

[21] In 1850, New York architect James Bogardus was hired by Baltimore Sun founder A.S. Abell to build a new headquarters for the newspaper, using the then-novel technique of cast-iron fronts.

While Bogardus preferred to use other, New York-based foundries with whom he had prior relationships for the actual exterior ironwork, Hayward & Bartlett was commissioned to cast the building's steam heating and plumbing systems.

[24] One of its most notable early works came in 1854 when the company built the cast-iron façade of Harper & Bros. Building in New York, considered a "masterpiece of the style.

"[25] In 1851, Hayward & Bartlett increased its production space, constructing a large, four-story warehouse in the cast-iron style for which they were becoming known, at Light and Mercer streets and adjacent to their existing offices.

[46] Hayward & Bartlett's experience with monumental iron works grew, as it cast what were reported as some of the largest girders in the world as part of the construction of the Peabody Institute in 1860.

[48] However, the company downplayed its participation in supplying one side over the other, owing to the delicate position of Baltimore between North and South (a tension which had recently exploded in the Baltimore riot of 1861), as well as the company's commercial entanglements with Southern governments, such as for the construction of the South Carolina State House, which Hayward & Bartlett had secured contract for in 1848, and would resume the construction of after the war's conclusion.

[50] With its owner imprisoned for the duration of the war, in 1863 the Winans yards were leased by Hayward, Bartlett & Co., who began producing railroad engines there under the name "Baltimore Locomotive Works.

[25] It also supplied much of the metalwork for the Treasury Building in Washington, D.C.[30] By the 1870s, Bartlett & Robbins was the largest iron foundry in the United States, employing between 500 and 1000 people at any given time.

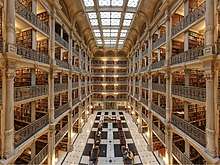

[3] The company at this time produced the elaborate cast-iron interior and railings of the George Peabody Library in Mount Vernon.

[64] In addition to its stoves, heating systems and iron architectural work, the company continued to diversify its products in this period, beginning to produce gas lighting fixtures.

[65] An advertisement from the time period shows how extensive the catalog of cast-iron products available had become, including: "walls, floors, doors, windows, roof, porticoes, balconies, cornices, vaults, ventilators, fences, gates, fountains, vases, statuary, chairs, settees, gas and water fixtures, a heating apparatus, ranges or cooking stoves, parlor stoves, grates, brackets, stable fixtures, iron pavements, pots and kettles, culinary implements, bedsteads, in fact everything except beds and bedding, and science will doubtless ere long find some means of remedying this apparent difficulty.

[73] Around this time, Bartlett, Hayward & Co. obtained several major national contracts, producing the heating and cooling systems for Johns Hopkins Hospital, New York Post Office, the New Orleans Custom House and the San Francisco Mint.

Several downtown buildings however avoided total destruction owing in part to protection from their Bartlett & Hayward-produced iron shutters, including the Mercantile Trust and Deposit Company.

[76] Owing to its acquisition of several elevator patents that same year, the company did a strong business participating in the reconstruction of the burned city's many commercial buildings.

[79][71] Thomas Hayward died in 1909, though shortly before this he had had the company publicly incorporated as Bartlett-Hayward Co., so that it might continue after direct family ownership ended.

[81] Beginning in 1915, Bartlett-Hayward produced many of the many munitions used by members of the Triple Entente during World War I, signing military contracts with Russia and France.

The company opened a large expansion plant at Sollers Point/Turner Station, spread over 55 acres and comprising 59 buildings & 6,000 workers, manufacturing toluene for high explosives, 75-millimeter, 4.7-inch artillery ammunition.

[97] This and other alloys enabled the company to produce many of the larger projects it undertook in the 1930s and 1940s, including pins for bridge bearings and piping and gates for dams.

[15] Due to the sophistication and scale of their operations at the time, Barlett-Hayward, along with other Baltimore-based peers like Poole and Hunt, found international prestige as "a virtual university for mechanics and machinists.

[108] In the immediate post-war period, the company was unionized: the International Association of Machinists Memorial Lodge #1784 represented workers at the site beginning in 1948.

[109] However, in the context of a broader gradual deindustrialization in Baltimore, the staff at all of the Bartlett-Hayward division locations in the city fell to between 3,600 and 2,900 (reports vary) by 1975.

[110][111] Nevertheless, the Bartlett Hayward plant continued to be busy - that same year saw a record backlog of orders for the coke oven doors machined there.

[113][114] At this point the firm also maintained Baltimore-area sites at Bush and Hamburg street (on the edge of Pigtown) where it produced seals and piston rings, a power transmission plant in Harmans and a container machinery factory at Glen Arm.

[15] That year, the city proposed for several of the vacant 19th-century buildings at the complex to be retrofitted as townhouses and was prepared to offer a matching grant to encourage private investment in the scheme.