Health in Ethiopia

Health in Ethiopia has improved markedly since the early 2000s, with government leadership playing a key role in mobilizing resources and ensuring that they are used effectively.

A central feature of the sector is the priority given to the Health Extension Programme, which delivers cost-effective basic services that enhance equity and provide care to millions of women, men and children.

[2] In regards to the right to health amongst the adult population, the country achieves only 90.6% of what is expected based on the nation's level of income.

Because of growing population pressure on agricultural and pastoral land, soil degradation, and severe droughts that have occurred each decade since the 1970s, per capita food production is declining.

[4] Shortage and high turnover of human resource and inadequacy of essential drugs and supplies have also contributed to the burden.

The HEP is designed to deliver health promotion, immunization and other disease prevention measures along with a limited number of high-impact curative interventions.

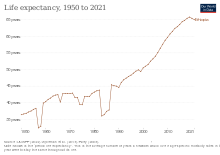

[7] Life expectancy is better in cities compared to rural areas, but there have been significant improvements witnessed throughout the country as of 2016, the average Ethiopian living to be 62.2 years old, according to a UNDP report.

[12] Nearly 60 percent of the population lives in areas at risk of malaria, generally at elevations below 2,000 meters above sea level.

[12] Because peak transmission coincides with the planting and harvesting season, malaria places a heavy economic burden on the country.

[12] The Carter Center conducted research in Ethiopia in the mid-2000s where they analyzed how malaria affects the Ethiopian population among various factors.

[13] Researchers concluded that a key method of reducing the prevalence of malaria in Ethiopia is by improving the quality of housing and living conditions.

[13] This research also concluded that while the poorest households are more likely to face these poor conditions, they are also the ones less likely to take steps towards malaria prevention, thus continuing transmission of the disease.

[13] The Carter Center chose three specific areas in Ethiopia to assess the impact of the use of insecticide treated mosquito nets on malaria prevalence.

[14] This study has revealed the importance and effectiveness of malaria prevention in Ethiopia, and thus has led to health workers promoting the use of these long lasting insecticidal nets in areas where use is still limited and disease prevalence is highest.

[14] A research study done by the Ethiopian Public Health Institute revealed flaws with Ethiopia's laboratories and their workers as it pertains to malaria diagnosis.

[15] The study found 26.7% of the 106 Ethiopian laboratories assessed lacked adequate supplies needed for proper diagnosis.

[15] Researchers attributed this to multiple factors, such as insufficient lab funding and supporting third parties not providing supplies in a timely manner.

The 2015/16 National STEPS Survey on NCDs and risk factors showed the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes is 15.6% and 3.2% respectively among the adult population.

The effort to control tuberculosis began in the early 60s with the establishment of TB centers and sanatoria in three major urban areas in the country.

In 1992, a well-organized TB program incorporating standardized directly observed short course treatment (DOTS) was implemented in a few pilot areas of the country.

This vertical program was well funded and has scored notable achievements in reducing the prevalence of leprosy, especially after the introduction of Multiple Drug Therapy (MDT) in 1983.

This has encouraged Ethiopia to consider integration of the vertical leprosy control program with in the general health services.

Additionally, the survey showed a higher prevalence rates for smear positive and bacteriologically confirmed TB in pastoralist communities.

The pregnancy related mortality has also dropped over the last three surveys and this could be attributed to the improvement on skilled delivery and family planning.

[citation needed] The "WHO estimates that a majority of maternal fatalities and disabilities could be prevented if deliveries were to take place at well-equipped health centres, with adequately trained staff".

[36] FGM is a pre-marital custom mainly endemic to Northeast Africa and parts of the Near East that has its ultimate origins in Ancient Egypt.

Ethiopia's 2005 Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) noted that the national prevalence rate is 74% among women ages 15–49.

Today there are three medical schools in Ethiopia that began training students in 1965 two of which are linked to Addis Ababa University.

Although there have been huge leaps and bounds in medical technology there is still a large problem in the distribution of medicine and doctors in Ethiopia.

[63] Experts have observed that CBHI can only play a limited role in achieving universal health coverage for various reasons.