Health economics

[2] In broad terms, health economists study the functioning of healthcare systems and health-affecting behaviors such as smoking, diabetes, and obesity.

[3] A seminal 1963 article by Kenneth Arrow is often credited with giving rise to health economics as a discipline.

[4] Factors that distinguish health economics from other areas include extensive government intervention, intractable uncertainty in several dimensions, asymmetric information, barriers to entry, externality and the presence of a third-party agent.

[citation needed] Health economists evaluate multiple types of financial information: costs, charges and expenditures.

For example, making an effort to avoid catching the common cold affects people other than the decision maker[6][7][8]: vii–xi [9] or finding sustainable, humane and effective solutions to the opioid epidemic.

The scope of health economics is neatly encapsulated by Alan Williams' "plumbing diagram"[10] dividing the discipline into eight distinct topics:

In the third century BC, Aristotle, an ancient Greek thinker, once talked about the relationship between farmers and doctors in production and exchange.

[11] In the 17th century, William Petty, a British classical economist, pointed out that the medical and health expenses spent on workers would bring economic benefits.

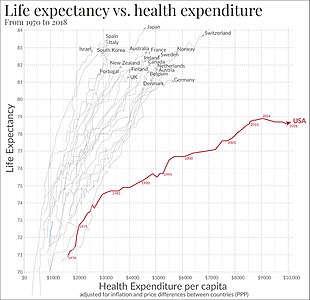

[14] At the same time, the expenditure on health care in many European countries also increased, accounting for about 4% of GDP in the 1950s and 8% by the end of the 1970s.

In terms of growth rate, the proportion of health care expenditure in GNP (gross national product) in many countries increased by 1% in the 1950s, 1.5% in the 1960s, and 2% in the 1970s.

This high medical and health expenditure was a heavy economic burden on government, business owners, workers, and families, which required a way to restrain its growth.

Probably, the single most famous and cited contribution to the discipline was Kenneth Arrow's "Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care", published in 1963.

[18] After the 1970s, the health economy entered a period of rapid development and nursing economics gradually emerged.

The model makes predictions over the effects of changes in prices of healthcare and other goods, labour market outcomes such as employment and wages, and technological changes.

Economic evaluation, and in particular cost-effectiveness analysis, has become a fundamental part of technology appraisal processes for agencies in a number of countries.

The resulting moral hazard drives up costs, as shown by the RAND Health Insurance Experiment.

Consumers in healthcare markets often lack adequate information about what services they need to buy and which providers offer the best value proposition.

Health economists have documented a problem with supplier induced demand, whereby providers base treatment recommendations on economic, rather than medical criteria.

[22] Risk-sharing can reduce risk premiums, for example for research and development of new cures and health care equipment.

Mental health can be directly related to economics by the potential of affected individuals to contribute as human capital.

[32] Externalities may include the influence that affected individuals have on surrounding human capital, such as at the workplace or in the home.

For example, studies in India, where there is an increasingly high occurrence of western outsourcing, have demonstrated a growing hybrid identity in young professionals who face very different sociocultural expectations at the workplace and in at home.

Further, employment statistics are often used in mental health economic studies as a means of evaluating individual productivity; however, these statistics do not capture "presenteeism", when an individual is at work with a lowered productivity level, quantify the loss of non-paid working time, or capture externalities such as having an affected family member.

Also, considering the variation in global wage rates or in societal values, statistics used may be contextually, geographically confined, and study results may not be internationally applicable.

[35] Evers et al. (2009) have suggested that improvements could be made by promoting more active dissemination of mental health economic analysis, building partnerships through policy-makers and researchers, and employing greater use of knowledge brokers.

[33] Generally, economists assume that individuals act rationally with the aim of maximizing their lifetime utility, while all are subject to the fact that they cannot buy more than their resources allow.

A plot graph of an individual's stock of health throughout their lifetime would be steadily increasing in the beginning during their childhood, and after that gradually decline because of aging, meanwhile having sudden drops created by random events, such as injury or illness.

[37] There are many other things than "random" health care events, which individuals consume or do during their lives that affect the speed of aging and the severity and frequency of the drops.

The variable X, the bundle of goods and services, can undertake numerous characteristics, some add value while others noticeably decrease the stock of health.

Outstanding among such lifestyle choices are the decision to consume alcohol, smoke tobacco, use drugs, composition of diet, amount of exercise and so on.