Health in China

At that time the party began to mobilize the population to engage in mass "patriotic health campaigns" aimed at improving the low level of environmental sanitation and hygiene and attacking certain diseases.

[17] Instead, according to Blumenthal et al. (2005), individual towns were now responsible for ensuring that people were receiving adequate health care, which caused disparities between wealthier and poorer regions.

The lack of financial resources for the cooperatives resulted in a decrease in the number of barefoot doctors, which meant that health education and primary and home care suffered and that in some villages sanitation and water supplies were checked less frequently.

Also, the failure of the cooperative health care system limited the funds available for continuing education for barefoot doctors, thereby hindering their ability to provide adequate preventive and curative services.

If the patients could not pay for services received, then the financial responsibility fell on the hospitals and commune health centers, in some cases creating large debts.

But soon farmers demanded better medical services as their incomes increased, bypassing the barefoot doctors and going straight to the commune health centers or county hospitals.

The leaders of brigades, through which local health care was administered, also found farming to be more lucrative than their salaried positions, and many of them left their jobs.

Their income for many basic medical services limited by regulations, Chinese grassroots health care providers has supported themselves by charging for giving injections and selling medicines.

[16] One big issue many have pointed out, including Blumenthal (2005) and Yip et al. (2008), is that much of China's population does not have access to affordable health insurance.

[17] Dong (2008) also mentions that China has been working to reinstate the cooperative medical systems in rural areas by pushing for state-funded health centers to be established.

[20] That being said, some studies, such as Dib (2008) have shown that the quality of health care in rural areas still varies widely depending on wealth of the region.

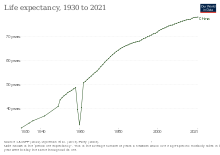

There are health related parameters: In general, all indices showed improvement except the drop around 1960 due to the failure of the Great Leap Forward, which led to the starvation of tens of millions of people.

[27] The One-child policy was a program created by the Chinese government as a reaction to the increasing population during the 1970s, that was thought to have negatively impacted China's economic growth.

[28] The policy was unevenly implemented throughout China and was easier established in urban areas rather than rural, because of ideals about family size and gender preferences.

[28] In terms of positive outcomes, as Zeng and Hesketh (2016) explain, the Chinese government cites the decreased fertility rate resulting from the one-child policy as a determining factor in China's rapidly increasing GDP.

[30] However, Zeng and Hesketh (2016) as well as Zhang (2017) also mention that other scholars argue China's fertility rate would have decreased as the country became more and more developed, regardless of whether the one-child policy had been in place or not.

[36] After a decline from 2014 to 2016 as several major Chinese cities introduced tough indoor smoking bans, cigarette sales are still rising, reaching 2.44 trillion in 2023.

The 2002 SARS in China demonstrated at once the decline of the PRC epidemic reporting system, the deadly consequences of secrecy on health matters and, on the positive side, the ability of the Chinese central government to command a massive mobilization of resources once its attention is focused on one particular issue.

[60] The AIDS disaster of Henan in the mid-1990s is estimated to be the largest man-made health catastrophe, affecting five-hundred thousand to one million persons.

[65] China, similar to other nations with migrant and socially mobile populations, has experienced increased incidences of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS).

Within China, the rapid increase in venereal disease, prostitution and drug addiction, internal migration since the 1980s and poorly supervised plasma collection practices, especially by the Henan provincial authorities, created conditions for a serious outbreak of HIV in the early 1990s.

[76] In the 2000–2002 period, China had one of the highest per capita caloric intakes in Asia, second only to South Korea and higher than countries such as Japan, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

In 2002, Svedberg found that stunting rate in rural areas of China was 15 percent, reflecting that a substantial number of children still suffer from malnutrition.

One possible reason for poor nutrition in rural areas is that agricultural produce can fetch a decent price, and thus is often sold rather than kept for personal consumption.

A girl named Wang Jing in China has a bowl of pork only once every five to six weeks, compared to urban children who have a vast array of food chains to choose from.

[84] In Liu et al.'s research (2018) on this issue specifically, the major health effects are listed as "including adverse cardiovascular, respiratory, pulmonary, and other health-related outcomes".

[86] Finally, as described by Kan (2018) and Wu, et al. (1999) another major contributor to adverse health effects related to environmental issues is water pollution.

The lack of reliable drinking water and sanitation areas, along with many others health issues, has directly led to 1/3 of young students in China having intestinal parasites.

The programs and policies are used to teach students about basic hygiene and form campaigns encouraging people to wash their hands with soap instead of water only.

At the same time, in an ever-interconnected world, China has embraced its responsibility to global public health, including the strengthening of surveillance systems aimed at swiftly identifying and tackling the threat of infectious diseases such as SARS and avian influenza.