Healthcare rationing in the United States

[1][2] The poor are given access to Medicaid, which is restricted by income and asset limits by means-testing, and other federal and state eligibility regulations apply.

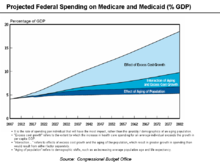

[4][5][6] The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has argued that health care costs are the primary driver of government spending in the long term.

But our current system of employer-financed health insurance exists only because the federal government encouraged it by making the premiums tax deductible.

In 2008, Tia Powell led a New York State work group to set up guidelines for rationing ventilators during a potential flu pandemic.

[10] President Obama noted that US healthcare was rationed based on income, type of employment, and pre-existing medical conditions, with nearly 46 million uninsured.

It also found that policyholders with breast cancer, lymphoma, and more than 1000 other conditions were targeted for rescission and that employees were praised in performance reviews for terminating the policies of customers with expensive illnesses.

[17] Polling has discovered that Americans are much more likely than Europeans or Canadians to forgo necessary health care (such not seeking a prescribed medicine) on the grounds of cost.

[citation needed] According to a recent survey commissioned by Wolters Kluwer, the majority of physicians and nurses (79%) say the cost to the patient influences the treatment choices or recommendations the provider makes.

[4] After the death of Coby Howard in 1987[19] Oregon began a programme of public consultation to decide which procedures its Medicaid program should cover in an attempt to develop a transparent process for prioritizing medical services.

His mother spent the last weeks of his life trying to raise $100,000 to pay for a bone marrow transplant, but the boy died before treatment could begin.

[24] Ezra Klein described in the Washington Post how polls indicate senior citizens are increasingly resistant to healthcare reform because of concerns about cuts to the existing Medicare program that may be required to fund it.

[26] A concept called "quality-adjusted life year" (QALY - pronounced "qualy") is used by Australian Medicare to measure the cost-benefit of applying a particular medical procedure.

Australia applies QALY measures to control costs and ration care and allows private supplemental insurance for those who can afford it.

Such scenarios offer the opportunity to maintain or improve the quality of care while significantly reducing costs through comparative effectiveness research.

Writing in the New York Times, David Leonhardt described how the cost of treating the most common form of early-stage, slow-growing prostate cancer ranges from an average of $2,400 (watchful waiting to see if the condition deteriorates) to as high as $100,000 (radiation beam therapy):[27] Some doctors swear by one treatment, others by another.

Economist Martin Feldstein wrote in the Wall Street Journal, "Comparative effectiveness could become the vehicle for deciding whether each method of treatment provides enough of an improvement in health care to justify its cost.

"[30] Former Republican Secretary of Commerce Peter George Peterson indicated that some form of rationing is inevitable and desirable considering the state of US finances and the trillions of dollars of unfunded Medicare liabilities.

have dubbed Governor Jan Brewer and the state legislatures as a real life death panel[citation needed] because many of those poor people who are now being denied funding will die or have health because of the political decision.

In the US, the discussion on rationing healthcare for the elderly began to be noticed widely in 1983 when economist Alan Greenspan asked "whether it is worth it" in referring to the use of 30% of the Medicare budget on 5–6% of those eligible who then die within a year of receiving treatment.

In 1984, the Democratic governor of Colorado, Richard Lamm, was widely quoted but claimed to have been misquoted as saying that the elderly "have a duty to die and get out of the way.

"[36][page needed] One book-length rebuttal to Callahan from half-a-dozen professors who held a conference at the University of Illinois College of Law in October 1989 was in 1991's Set No Limits: a Rebuttal to Daniel Callahan's Proposal to Limit Health, edited by Robert Laurence Barry and Gerard V. Bradley, a visiting professor of religious studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

If we ration we won't be writing blank checks to pharmaceutical companies for their patented drugs, nor paying for whatever procedures doctors choose to recommend.

In other words, all other federal spending categories (such as Social Security, defense, education, and transportation) would require borrowing to be funded, which is not feasible.