Heart Sutra

In the sutra, Avalokiteśvara addresses Śariputra, explaining the fundamental emptiness (śūnyatā) of all phenomena, known through and as the five aggregates of human existence (skandhas): form (rūpa), feeling (vedanā), volitions (saṅkhāra), perceptions (saṃjñā), and mind (vijñāna).

[6][7] While the origin of the sutra is disputed by some modern scholars,[e] it was widely known throughout South Asia (including Afghanistan) from at least the Pala Empire period (c. 750–1200 CE) and in parts of India until at least the middle of the 14th century.

[18] John McRae and Jan Nattier have argued that this translation was created by someone else, much later, based on Kumārajīva's Mahāprajñāpāramitāupadeśa (Great Treatise on the Perfection of Wisdom).

According to Huili's biography, Xuanzang learned the sutra from an inhabitant of Sichuan, and subsequently chanted it during times of danger on his journey to the West (i.e.

The second oldest extant dated text of the Heart Sutra is another stone stele located at Yunju Temple.

[25] All of the above stone steles have the same descriptive inscription : "(Tripitaka Master) Xuanzang was commanded by Emperor Tang Taizong to translate the Heart Sutra.

[32] According to Nattier, only 40% of the extant text of the Heart Sutra is a quotation from the Mahāprajñāpāramitāupadeśa (Great Treatise on the Perfection of Wisdom), a commentary on the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra written by Nāgārjuna and translated by Kumārajīva; while the rest was newly composed.

[33] Based on textual patterns in the extant Sanskrit and Chinese versions of the Heart Sūtra, the Mahāprajñāpāramitāupadeśa and the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, Nattier has argued that the supposedly earliest extant version of the Heart Sutra, translated by Kumārajīva (344-413),[n] that Xuanzang supposedly received from an inhabitant of Sichuan prior to his travels to India, was probably first composed in China in the Chinese language from a mixture of material derived from Kumārajīva's Chinese translation of the Mahāprajñāpāramitāupadeśa, and newly composed text (60% of the text).

[34] Nattier's hypothesis has been rejected by several scholars, including Harada Waso, Fukui Fumimasa, Ishii Kōsei, and Siu Sai Yau, on the basis of historical accounts and comparison with the extant Sanskrit Buddhist manuscript fragments.

[35][36][37][p][38][39][40] Harada and Ishii, as well as other researchers such as Hyun Choo and Dan Lusthaus, also argue that evidence can be found within the 7th-century commentaries of Kuiji and Woncheuk, two important disciples of Xuanzang, that undermine Nattier's argument.

[41][q][42][r][36][s][43][t] Li states that of the Indic Palm-leaf manuscript (patra sutras) or sastras brought over to China, most were either lost or not translated.

[u] Red Pine, a practicing American Buddhist, favours the idea of a lost manuscript of the Large Perfection of Wisdom Sutra (Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra) with the alternate Sanskrit wording, allowing for an original Indian composition,[44] which may still be extant, and located at the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda.

[v][w] Harada rejects Nattier's claims that the central role of Avalokiteśvara points to a Chinese origin for the Heart Sutra.

[y][z] However, the question of authorship remains controversial, and other researchers such as Jayarava Attwood (2021) continue to find Nattier's argument for a Chinese origin of the text most convincing explanation.

In Tibet, Mongolia and other regions influenced by Vajrayana, it is known as The [Holy] Mother of all Buddhas Heart (Essence) of the Perfection of Wisdom.

They are as follows: e.g. Korean: Banya Shimgyeong (Korean: 반야심경); Chinese:Bo Re Xin Jing(Chinese: 般若心经; pinyin: bō rě xīn jīng);Japanese:Hannya Shingyō (Japanese: はんにゃしんぎょう / 般若心経); Vietnamese (Vietnamese: Bát nhã tâm kinh,般若心經).

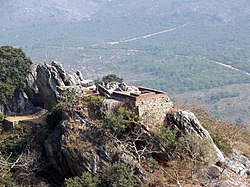

In the longer version, there exists the traditional opening "Thus have I heard" and Buddha along with a community of bodhisattvas and monks gathered with the bodhisattva of great compassion, Avalokiteśvara, and Sariputra, at Gridhakuta (a mountain peak located at Rajgir, the traditional site where the majority of the Perfection of Wisdom teachings were given).

Through the power of Buddha, Sariputra asks Avalokiteśvara[50]: xix, 249–271 [ac][51]: 83–98 for advice on the practice of the Perfection of Wisdom.

The longer sutra then describes, while the shorter opens with, the liberation of Avalokiteśvara, gained while practicing the paramita of prajña (wisdom), seeing the fundamental emptiness (śūnyatā) of the five skandhas: form (rūpa), feeling (vedanā), volitions (saṅkhāra), perceptions (saṃjñā), and consciousness (vijñāna).

Avalokiteśvara addresses Śariputra, who was the promulgator of abhidharma according to the scriptures and texts of the Sarvastivada and other early Buddhist schools, having been singled out by the Buddha to receive those teachings.

On this basis, Red Pine has argued that the Heart Sūtra is specifically a response to Sarvastivada teachings that, in the sense "phenomena" or its constituents, are real.

All Buddhas of the three ages (past, present and future) rely on the Perfection of Wisdom to reach unexcelled complete Enlightenment.

The final lines of the Heart Sutra can be read in two different ways, depending on the interpretation of the character 咒, zhòu, meaning either mantra (danini), or "a superlative kind of practical knowledge or incantation (vidyā).

[59] In the longer version, Buddha praises Avalokiteśvara for giving the exposition of the Perfection of Wisdom and all gathered rejoice in its teaching.

Many schools traditionally have also praised the sutra by uttering three times the equivalent of "Mahāprajñāpāramitā" after the end of the recitation of the short version.

In modern times, the text has become increasingly popular amongst exegetes as a growing number of translations and commentaries attest.

The 1782 Japanese text "The Secret Biwa Music that Caused the Yurei to Lament" (琵琶秘曲泣幽霊), commonly known as Hoichi the Earless, because of its inclusion in the 1904 book Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, makes usage of this Sūtra.

It involves the titular Hoichi having his whole body painted with the Heart Sūtra to protect against malicious spirits, with the accidental exception of his ears, making him vulnerable nonetheless.

[95] The Sanskrit mantra of the Heart Sūtra was used as the lyrics for the opening theme song of the 2011 Chinese television series Journey to the West.

[98] Bear McCreary recorded four Japanese-American monks chanting in Japanese, the entire Heart Sūtra in his sound studio.