Hearts and Minds (film)

The film's title is based on a quote from President Lyndon B. Johnson: "the ultimate victory will depend on the hearts and minds of the people who actually live out there".

Commercial distribution was delayed in the United States due to legal issues, including a temporary restraining order obtained by one of the interviewees, former National Security Advisor Walt Rostow, who had claimed through his attorney that the film was "somewhat misleading" and "not representative" and that he had not been given the opportunity to approve the results of his interview.

"[4][5][6] A scene described as one of the film's "most shocking and controversial sequences" shows the funeral of a South Vietnamese soldier and his grieving family, as a sobbing woman is restrained from climbing into the grave after the coffin.

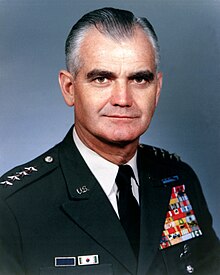

[7] The funeral scene is juxtaposed with an interview with General William Westmoreland—commander of American military operations in the Vietnam War at its peak from 1964 to 1968 and United States Army Chief of Staff from 1968 to 1972—telling a stunned Davis that "The Oriental doesn't put the same high price on life as does a Westerner.

[8][9] Davis later reflected on this interview stating, "As horrified as I was when General Westmoreland said, 'The Oriental doesn’t put the same value on life,' instead of arguing with him, I just wanted to draw him out...

[11] One of the film's earliest scenes details a homecoming parade in Coker's honor in his hometown of Linden, New Jersey, where he tells the assembled crowd on the steps of city hall that, if the need arose, they must be ready to send him back to war.

The camera, which amply records the agonies of South Vietnamese political prisoners, seems uninterested in the American lieutenant's experience of humiliation and torture.

[22] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film an "epic documentary ... [that] recalls this nation's agonizing involvement in Vietnam, something you may think you know all about, including the ending.

"[23] Desson Thomson of The Washington Post described it as "one of the best documentaries ever made, a superb film about the thoughts and feelings of the era, the whole festering, spirited animus of it.

[28] David Dugas of United Press International, in a 1975 review printed in Pacific Stars and Stripes, said that "Davis' approach clearly is one-sided and is not likely to impress Vietnam hawks.

"[3] M. Joseph Sobran, Jr. of the conservative magazine National Review, writing in 1975, called the film a "blatant piece of propaganda ... disingenuously one-sided ..." and went on to show the cinematic techniques used by the producers to achieve this effect.

During his acceptance speech for the Academy Award for Best Documentary, Feature, on April 8, 1975, co-producer Bert Schneider said, "It's ironic that we're here at a time just before Vietnam is about to be liberated" and then read a telegram containing "Greetings of Friendship to all American People" from Ambassador Dinh Ba Thi of the Provisional Revolutionary Government (Viet Cong)[32] delegation to the Paris Peace Accords.

Without question, it takes the anti-war side of things, and one could argue it goes for a pro-Vietnamese bent as well....In the end, Hearts and Minds remains a flawed film that simply seems too one-sided for its own good.